Review: At the Hammer Museum, Andrea Bowers' art becomes an act of nonviolent civil disobedience

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Vice President Kamala Harris, then still a senator from California, faced Supreme Court candidate Brett Kavanaugh during his 2018 confirmation hearing, she brought the proceeding to an abrupt standstill with one shrewd question: “Can you think of any laws that give government the power to make decisions about the male body?”

Kavanaugh was stunned. He stared blankly into space; a proverbial deer was caught in the headlights.

After six long seconds spent mostly blinking his eyes, he stammered, “Uh … I’m happy to take more specific questions.” No doubt. Surely, he had been prepared to answer inquiries about Roe vs. Wade and the issue of established precedent, as every nominee to the court — and especially every Republican nominee selected for their personal, conservative Catholic antiabortion views — knew they would be asked.

The hemming, hawing, staring and blinking continued, until Harris repeated the question. “I’m not … I’m not thinking of any,” Kavanaugh finally conceded. That particular chicken finally came home to roost two weeks ago, nearly four years after the trenchant exchange, when the justice voted to strip women of a constitutionally protected right to seek abortion care.

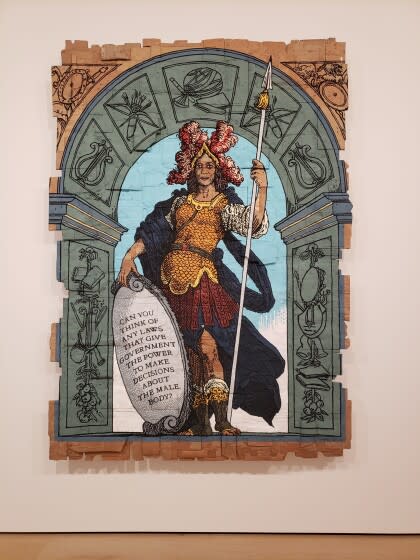

In the nearly 25-year survey of Andrea Bowers’ art newly opened at the UCLA Hammer Museum, Harris’ unforeseen but revealing question is enshrined in a monumental drawing made of the humblest materials. Bowers' career as an artist is embedded in socially conscious engagement with many contentious issues, including women’s bodily autonomy, immigration, ecological disaster and human rights.

The slightly larger-than-life figure in colored acrylic marker on salvaged pieces of cardboard presents Harris in the elaborately helmeted guise of Athena. The Olympian goddess of wisdom and war is also the Greek deity associated with handicrafts, linking the senator’s incisive inquiry with the very materials from which the image is made. Bowers has a marvelous, even essential way with making the subjects of her works inseparable from their formal perfection.

Dressed for battle in chain mail and boots, Harris trails an indigo blue robe that dramatically flows behind her, as if she just strode into commanding view. The heroine stands beneath a triumphal arch in which imagery of the weapons of war alternate with symbols of knowledge and the arts. A pointed spear is planted in her left hand, a shieldlike cartouche in her right, its surface etched with the devastating Kavanaugh question, now permanently enshrined.

The overall design comes from 17th century France. Bowers adapted the anonymously made, black-and-white frontispiece engraving to the book “Illustrious Women or Heroic Harangues,” a series of philosophical dialogues written by the egalitarian French feminist Madeleine de Scudéry (1607–1701). (The very long title of Bowers’ drawing carefully identifies the details of all its sources, from the Senate hearing room to the writer’s Parisian salon.) Recast in vivid color, the frontispiece is enlarged to life-size scale, swapping out a generic female face for a specific one. Harris’ gendered question is visually framed within Scudéry’s pioneering discourse, which immediately preceded the Age of Enlightenment.

Centuries have passed, but the fight then is still a fight now — and it has been throughout history, as the foundation in the 2,500-year-old Greek myth of Athena implies. Even the recycled cardboard cleverly evokes a considered recovery of energy from used materials. Bowers’ work might seem unusually topical, given such recent events as the Supreme Court attacks on abortion and the Environmental Protection Agency, but in reality, those are contested subjects with a long shelf life. Her brilliant Harris image, part fierce celebration and part cautionary tale, projects the uncomfortable truth that the price of liberty is indeed eternal vigilance.

Bowers, born in the small Ohio town of Wilmington in 1965, studied first at Bowling Green State University and then the California Institute of the Arts, where feminist and Conceptual art were mainstays in the curriculum and she received her master of fine arts in 1992. She’s lived and worked in Los Angeles ever since. The exhibition, which includes about 90 drawings, sculptures, videos, installations and mixed-media works, was jointly organized by Hammer chief curator Connie Butler and Michael Darling, former chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, where it was seen last winter.

The show is loosely arranged by social justice theme, beginning with abortion and women’s bodily autonomy. Just inside the entry, an electric sign 6 feet tall and 10 feet wide flashes in pink and yellow lights: “My Body My Choice Her Body Her Choice.” Notably, the wall sculpture was made in 2017 — the year that then-President Donald Trump, who campaigned on a pledge to make Supreme Court nominations to overturn Roe vs. Wade, was sworn into office and completed his first fateful appointment. The sign’s housing is constructed from cardboard packing boxes, employed to deliver the pronouncement.

Across the room from the Harris work, a 2005 installation on the same subject wraps a corner. A giant checkerboard papers two walls, interspersing colorful sheets of gift-wrapping paper with women’s letters of yearning and thanks to a trio of Bay Area women later dubbed the Army of Three, an activist group that provided abortion information prior to Roe. The emotional and wrenching letters, each one copied by hand by the artist on a fresh sheet of paper, become drawings akin to Photorealist renderings, while also asserting kinship and solidarity between artist and absent subject.

The wrapping paper underscores the larger installation’s qualities of being a gift — to the assisted women from the Army of Three, from the activists to the artist, and from the artist to the viewer. Bowers’ works typically create a vivifying tautness between the individual and the group. I think of her as the E pluribus unum artist, making the national motto — out of many, one — visually and materially manifest.

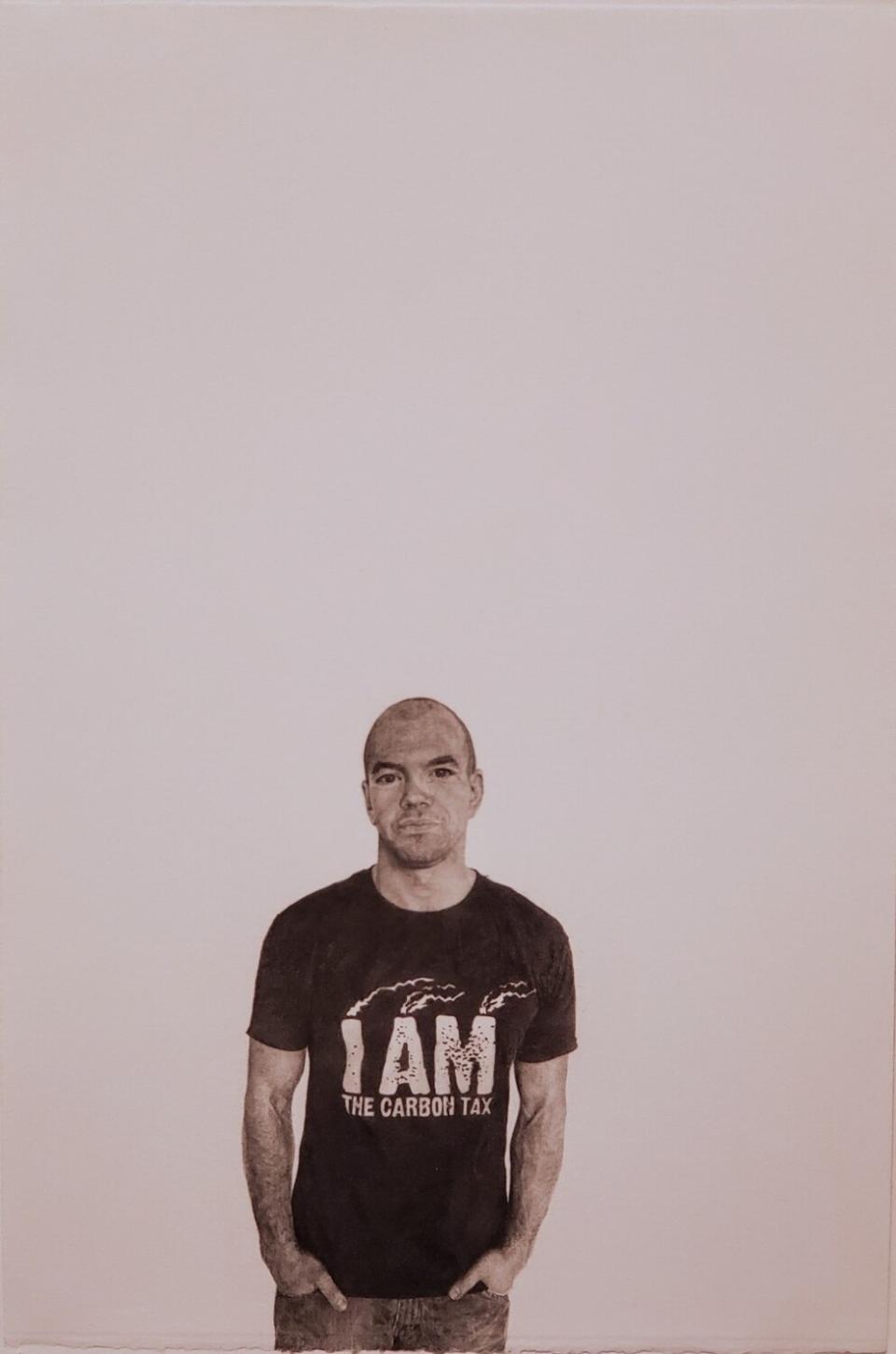

That all-American maxim, which attempts to parse the seemingly conflicting power of the individual and the collective, finds its first iteration in drawings begun around 1997 and continuing today. Perhaps her most well-known works, they derive from photographs taken at protest marches and meetings. From the crowds, Bowers isolates one and sometimes two people, often carrying a sign or wearing a sloganeering T-shirt. She carefully draws the figures in colored pencil, surrounded by a large field of plain white space.

As with the Army of Three letters, the transcription by hand is important. On one level, it evokes the elusive condition of artistic thought, as drawing is historically the most direct link between mind and art object. On another, it is a straightforward indication of manual labor, which connects the work of art to the work of activism. Each protesting figure with a sign or shirt emblazoned with a demand for “People before profits” or asking, “Who would Jesus deport?” is a site of focused energy, while the seemingly empty field of white paper is a site where you know others have joined in or will.

Bowers’ art would not succeed if she were talking down, lecturing or trying to convince a viewer of something. That’s why occasional critical complaints that her art won’t change anyone’s mind about social justice issues miss the mark. While she no doubt would not object if it did, the work instead seems grounded in embodying an ethical position of palpable generosity.

Once in a while, things do get muddled. Her 2013 “Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut” is a hauntingly beautiful reminiscence of a pristine forest of 250 trees unceremoniously chopped down by Los Angeles County, which Bowers suggests through bits of gnarled wood gathered from the ruined site and suspended in a chandelier of bright green cords. (The outline of the hanging sculpture looks like a lynching tree.) But a related, anti-clearcutting “pirate ship” is a confusing assembly of paraphernalia, apparently used in nonviolent civil disobedience actions.

Bowers was arrested during a clearcutting protest — a drawing of her mug shot graces the cover of the show’s catalog — so her sincerity is hardly in doubt. And even the pirate ship has its wonderments. Before Bowers, I hadn’t thought of art as itself having the capacity to not merely represent but to actually be a work of nonviolent civil disobedience. The engrossing Hammer exhibition convincingly suggests as much.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.