Review: Heartbreak is all in a day's work in a timely novel about a nurse on edge

One night in the ’90s, nearly 50 million people watched George Clooney pretend to be a doctor. Today, there are far fewer nurses than that — 30 million and shrinking every year. Ninety percent are women. It’s not an easy job.

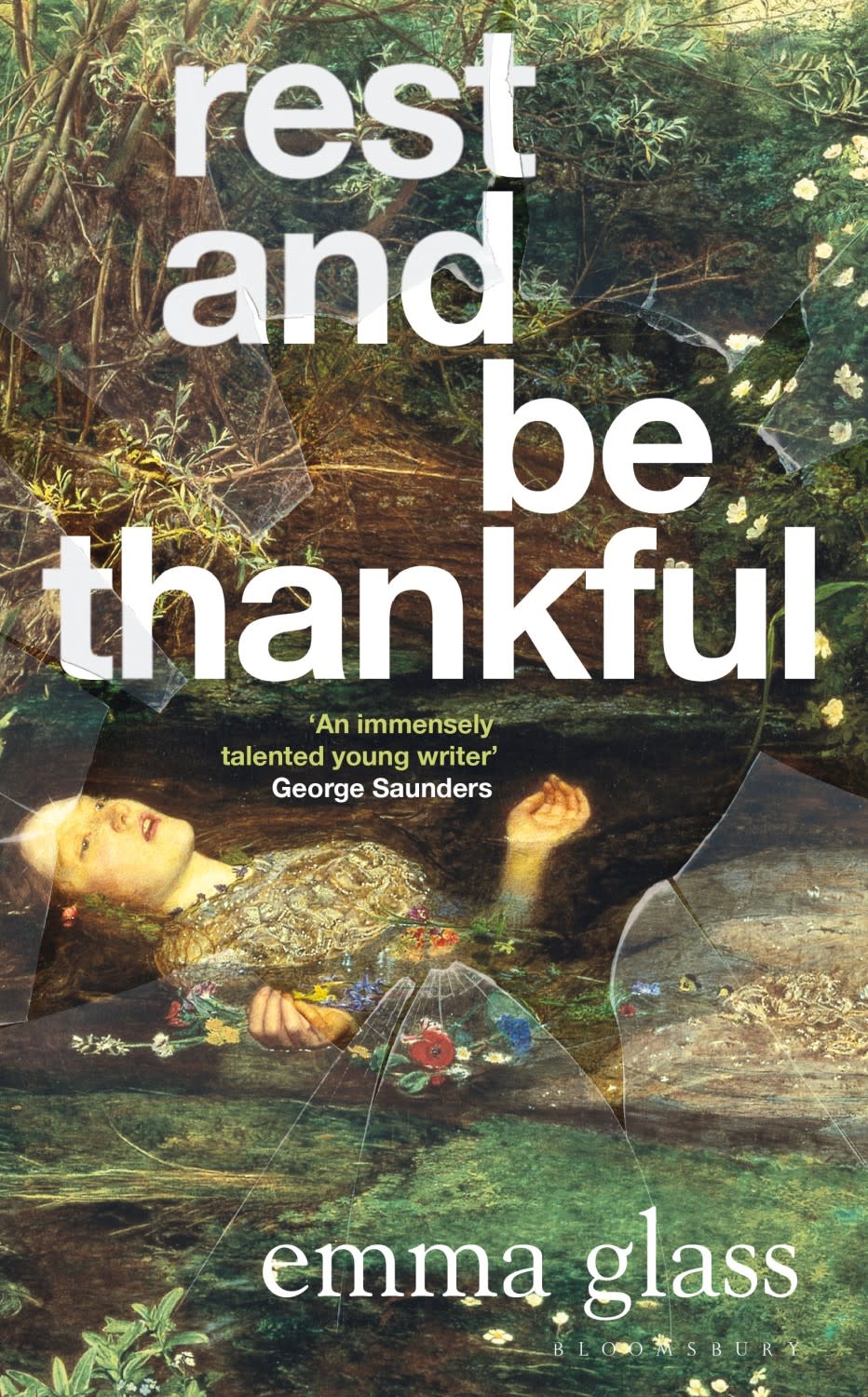

In a poetic but disjointed second novel, at times as harshly illuminating as a fluorescent-lighted operating room and at others as confusing as an overwhelmed ER, British writer Emma Glass — herself a working nurse — depicts a London hospital nursery ward where tiny humans struggle to survive. Her focus isn’t the suffering children but a few agonizing days in the life of one particular nurse, Laura, who is nearing complete systemic collapse. Is a faulty and unjust system to blame?

Laura has a bad boyfriend. She endures long hours and horrible nutrition. (The arrival of pizza one night is a significant event.) During a walk, she’s attacked by a bird. You’ll ache at the way she finally ditches the dude. “Self-care” is not a concept this caregiver is familiar with.

Glass’ character close-up generates the book’s most palpable and poignant scenes; they showcase Glass at her best. But the novel also gestures toward a larger story, one about a profession that gives its all and gets so little back. Even in times when our hospital system isn’t dangerously strained by an unprecedented pandemic, we ask our nurses — many of them nonwhite — to take care of us or our babies at our worst moments. Glass’ central question: How do they do it?

An early answer: one job at a time. “There are tools everywhere,” Laura thinks. “Tools for fixing the broken. I think of my father with his toolbox rattling. Opening, nails and screws rolling across the workbench. A wrench for this. A screwdriver. Holding still. And then the all-important squirt of oil.”

Through the eyes of Laura, who is both heroic and painfully fragile, we consider the brutal urgency of a hospital, the slow massacre of a ward, the savage blinking insanity of keeping a baby alive.

The closer we look at the machine, the closer it feels to disaster. “We will be told of the smooth, controlled management of the situation,” Laura sneers. “But I will remember the breaths missed, the shaking hands, the wrong-size tube, the dropped vials, the spilt fluid, the people, all the people aimlessly standing and staring and [soiling] themselves.”

Laura’s pain and exhaustion only raise the stakes, considering that she and her peers are the only people standing between order and utter collapse. She occasionally gives way to despair but finds hope while correcting a trainee’s mistake, gesturing at a larger code of ethics. “I only have bed 6,” the trainee tells Laura. “You mean you only have Florence today,” she shoots back — because names matter.

But heroic Laura is only as effective as the tools at hand and the system that employs her. There is, for instance, the doomed baby that can’t even be held by its mother without morphine to quell its pain. “She rocks him gently and I push the button, I give him a dose to keep him comfortable. I pause to watch for a moment while she whispers to him, brushing his cheek with a finger, the leads and wires coiling around her arms, they are tethered.”

The feeling of powerlessness is perhaps the worst part. The doctors in this novel make decisions. They are stormy and moody and might kiss you if you're not careful. But the nurses do the harder work of implementation, care, organization, and in dark rooms on the ward, they seem to suffer more greatly the consequences of messing up. Of betraying the patient. Of letting the doctor down. Of getting punished. Or worst of all, of having a baby not make it.

Glass’ intimate knowledge of nursing can make her details feel breathtakingly authentic — for instance, when she describes the grim ceremony of a conciliatory tea, accompanied by “the death china”: “The box feels flimsy, the lace is fake, everything worn,” Laura observes. “I wish we could do better.” The swaddling blankets are darkly colored, because when babies die they sometimes hemorrhage, and no parent should hold their child for the last time with a reddening towel.

And yet, Glass makes the curious decision to veer away from such stark realism. Laura is prone to hallucinations, which are described across too many chapters. One or two might have worked, but all the opaque searching and stumbling can make it feel as if Laura (and perhaps the author) is avoiding saying something more precise about what’s actually wrong here.

Another flaw is Glass’ tendency to amplify the pathos a few ticks too far. “These bears all used to belong,” Laura thinks, at length. “They were loved, hugged, dropped and caught. They were tucked up in bed and sat down to tea. And their love was cut off and they were brought here, set on shelves as tributes. Dust clings to them like children used to.” Sure, but it’s generally best, when broaching a subject like this, to tell the story with a simplicity closer to Hemingway’s six-word sentence.

Back in reality, there is little time to ponder forlorn teddy bears. Everyone's exhausted. The work is relentless. A patient moves on, whether to a warm bed or a cold grave. The emptied room is filled again. Another cup of coffee. Another day spent trying not to mess up. Glass, from her vantage point as a nurse and a gifted young author, makes much of an awesome opportunity to report from the front lines of a quiet war. One can’t help imagining that we’ll be reading many more of these sad stories for years to come.

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.