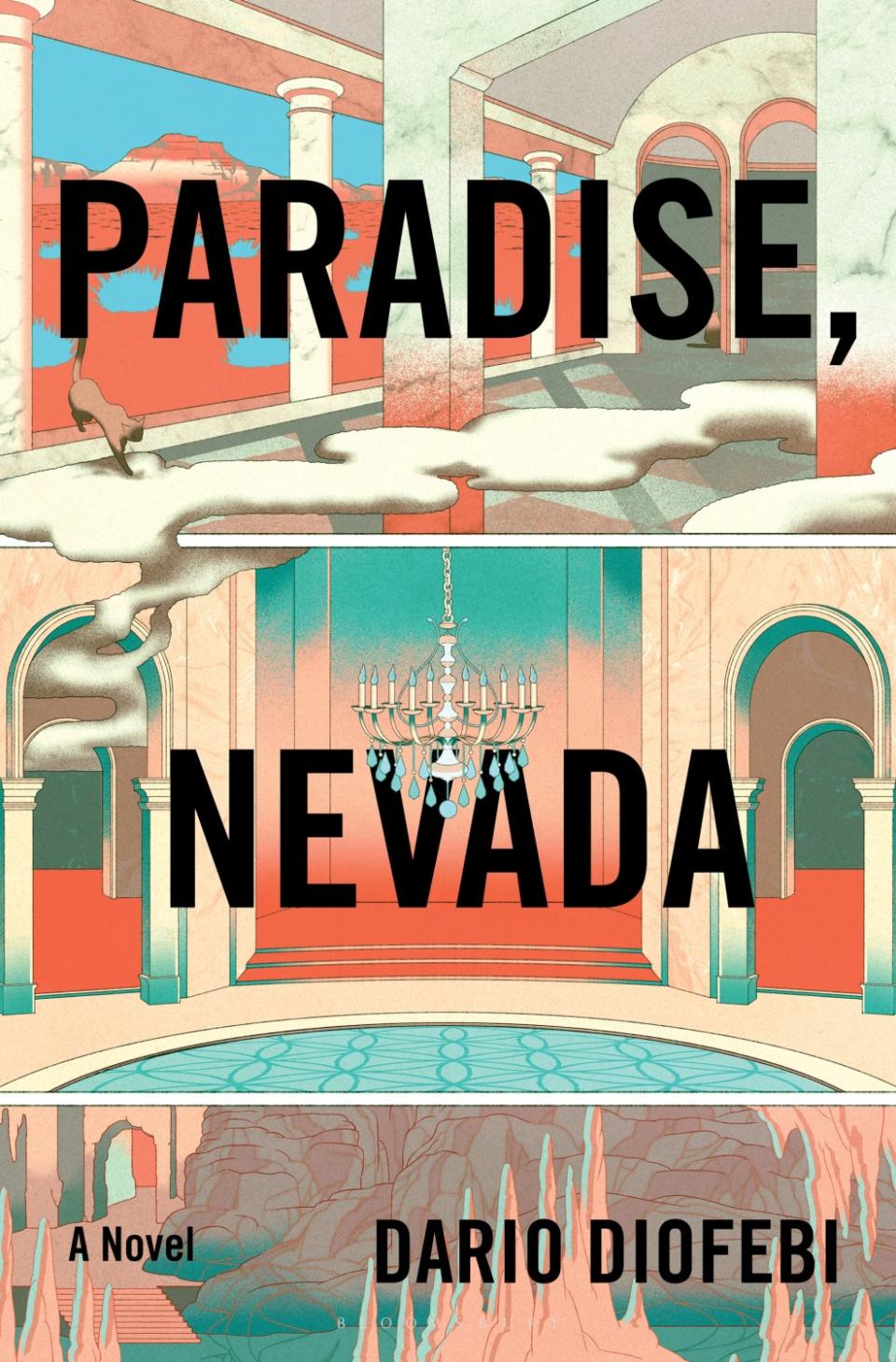

Review: An Italian immigrant poker pro takes a gamble on — what else? — a Fellini-esque Vegas novel

In another half century or so, some library will claim the papers of novelist Dario Diofebi toward the close of a distinguished career. Among the earliest documents will be some sort of outline or flow-chart for his debut, “Paradise, Nevada,” and the researcher who finds it will think they’ve stumbled into a three-ring circus. The term “carnivalesque” could’ve been coined with this novel in mind. Hijinks erupt even from the title, which one character reveals is the name of the township that encompasses most of Las Vegas. Its more common nickname is Sin City, and Diofebi’s hectic spectacular makes room for all its carrying on.

Each of the four major players, all shy of 30 and verging on a sea-change, take us into some core aspect of Vegas lore. The first, Ray, quit Stanford to pursue poker. At the tables, alas, his wizardly command of game theory keeps knocking up against the limits of his people skills. Mary Ann, on the other hand, seems to have it made with a union job at a swank casino. But as a “model-server” changing from one tarty costume to another, she feels nothing so much as a deepening self-loathing.

Tom — known as Tommaso back in working-class Rome — improvises a living in the shadows of Vegas, extending his vacation way past what U.S. law allows. Under the tutelage of the endlessly conniving Trevor, Tom recalls Roberto Benigni, a sad sack forever landing on his feet. Lindsay, the last of the group, seems to be the straight one, a journalist and a good Mormon girl. But with the help of her brother’s historical research, her reporting may put a stop to some of the worst usury on the Strip.

Predators are working angles all over town and they take all these characters for prey. But over six busy months, the foursome pushes back, forging sturdy new selves in the process. Mary Ann’s journey to wholeness may be the most moving, the richest; she winds up risking jail at the blackjack tables, scheming with a “shadow union.” But the ride’s wild for the entire quartet and some of Diofebi’s finest surprises are saved for the climax, which follows through on the Prologue’s ominous references to “the fire” and “the bomb.”

The elements would seem too various and too volatile for a first novelist. Diofebi is not much older than his protagonists, and a recent immigrant. His background suggests something of Tom’s, coming from Rome, but also Ray’s, in that he chucked a fine education for a career in poker — first online and then where else but Vegas? He picked up a lot beyond the game too. “Paradise” feels encyclopedic, rife with the arcana of casino operations as well as the entire region; it even ventures to Nevada’s nuclear waste dumps.

Now, a hyper-realistic funhouse ride doesn’t necessarily make for a convincing novel. This one intends a teeming human comedy, but it roves so widely among so many minor figures, that at times the spectacle flattens into farce. A lot of energy goes into pointing out the smoke and mirrors, always drawing the same moral: “God forbid there be anything close to sincere in this town.” While the leads all wrestle with their inner wimp, only Mary Ann’s struggle has mortal stakes. Surely one of these young people could’ve gotten out of their heads enough to fall in love.

Still, is it a criticism to say that Diofebi risks doing too much, too brilliantly? To say he recalls David Foster Wallace? His sharp eye for the flimflam renews our enchantment, as in this description of a hotel lobby:

“A crew of yellow-hatted men were disassembling Fall, the maples and oaks and pumpkins and squirrels and heartwarming colors of the falling leaves, and getting ready to install a snowy Christmas village.”

The passage lingers over its fakery, almost fond. The main verb, “disassembling,” registers more gently than, say “tearing down,” and is echoed by “heartwarming.” Subtleties like these, generating sympathy where we least expect it, are far beyond the abilities of a poker geek. (Diofebi did quit the tables to earn an MFA from New York University.)

The novel indulges in formatting tricks — footnotes à la Foster Wallace, plus email threads and more — but whatever the page looks like, the language highlights the flailing soul within. Even bit players enjoy moments of humanity. One recurring device has a flustered speaker mixing high rhetoric, the stuff of the university or Wikipedia, with tongue-tied filler. A pretty “dealertainer” in a bikini and high heels spouts Marxist ideology followed by, “um, pretty much.”

Trick by trick and hand after hand, Diofebi proves a gifted young maximalist. Around his desert oasis he gathers a fascinating crowd, then has them deliver a breathtaking choral celebration of “the real city they created, against all odds, at the heart of a glorified theme park.”

Domini’s memoir, “The Archeology of a Good Ragù,” will appear this May.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.