Review: Keith Haring's art might not be for everybody, but he is

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

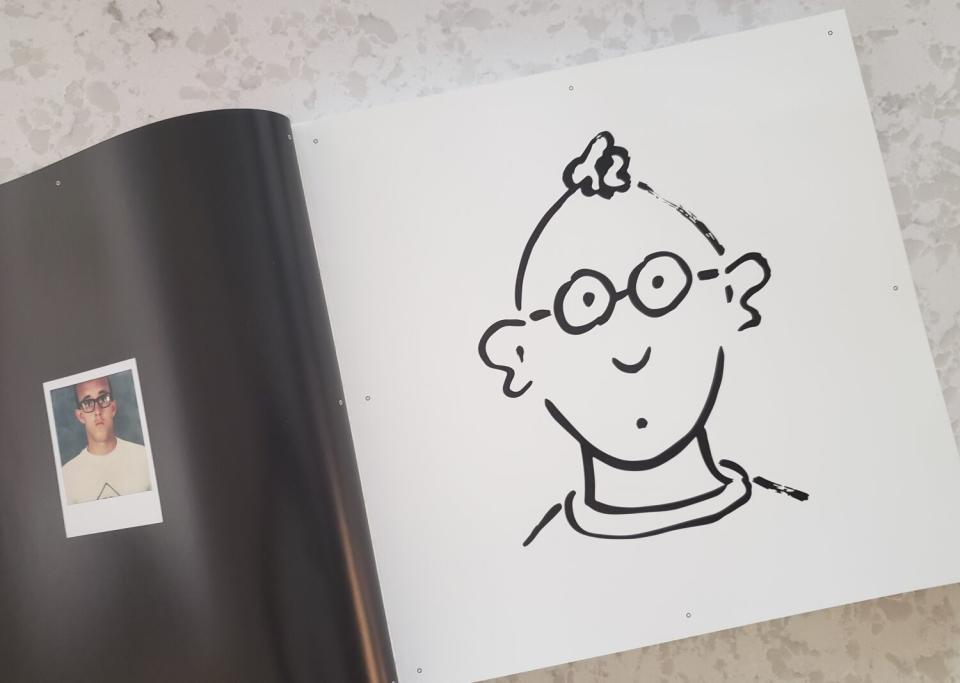

In the spring of 1989, just after turning 31 and about 10 months before he died, Keith Haring drew a self-portrait in black ink on white paper. It says a lot about the way he approached his work — both as motivation and as subject.

Except as a T-shirt, the self-portrait drawing by an iconic gay artist of a decade engulfed in a virulent conservative culture war is not included in “Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody,” the big survey (some 120 works) newly opened downtown at the Broad and arriving just in time for the celebration of LGBTQ+ Pride Month. But one of several versions does appear at the start of the large — and largely helpful — exhibition catalog. The image is rendered with a great economy of line, just about two dozen speedy strokes. Haring limned his oval head, the topknot above a receding hairline, a pair of prominent ears and eyes staring out from behind black-rimmed eyeglasses.

Just beneath the glasses are two simple marks that combine to marvelously animate the entire face. One is an upward curve, the other just below it is a dot.

Visually, these two facial marks read in two different ways: as a nose above a mouth making a surprised expression, as if uttering an unexpected “Oh!”; or, looked at another way, as a smile that has broken out above a prominent dimpled chin. The result is part carnivalesque caricature and part generic smiley face. A wide-eyed Haring represents himself as at once amazed and happy.

What he’s happy about is being an artist, I'd guess. That might amaze him, too.

Haring’s bio is well-known. Raised in tiny Kutztown, a rural Pennsylvania borough about 100 miles west of New York City, he enrolled in a Pittsburgh commercial arts school at 18. Soon growing tired of conventional mercantile demands on creativity, he quit. Barely 20 when he arrived in Manhattan, enrollment at the freewheeling School of Visual Arts and play in a flourishing downtown nightlife together set him on a new path. He came out of the closet, participated in shows in the thriving alternative art scene (including at dance clubs) and made friends with such like-minded artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf.

A breakthrough happened in 1980 — an “Oh!” moment, the first of many.

A habitual subway rider, Haring noticed the big, blank sheets of matte black paper employed to temporarily cover unused advertising panels. During travels through the urban underground, he began to draw on them with white chalk, making subway corridors into a kind of free public gallery. Although far from the glossy establishment showrooms on 57th Street, Madison Avenue or in Soho, the drawings also occupied commercial space. But they were hawking nothing other than their own exuberant imagery.

Call the subway drawings a discerning appropriation — one that reconciled his diverse experiences in Pittsburgh, at SVA and at Club 57 on St. Mark’s Place, helmed by artist and actor Ann Magnuson.

The other “Oh!” moments have to do with subject matter — gasps of joy, fury, disappointment, caution and more when it came to 1980s social conditions at home and abroad. Some gave prominence to pleasurable fun, like using loud Day-Glo paints that would interrupt the contemplative quiet of a typically hushed art gallery with the vivid exuberance found on a packed gay bar’s liberating dance floor. Others were sober — imagery linked to political repression, the perpetual threat of nuclear annihilation, apartheid cruelty, Reagan-era greed, culture war incited by hate from the religious right, apathy toward the exploding AIDS crisis and more.

A number of these subjects — too many — are still pressing today. HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, for example, was identified 40 years ago last month; but there still isn’t a vaccine. (An explicitly unfinished 1989 Haring painting is a moving declaration of impending loss.) Notable topical relevance characterizes the show, although the art was made as much as four decades ago.

At the Broad, curator Sarah Loyer has grouped works thematically, virtually wallpapering many of the 10 galleries, floor to ceiling. The show focuses on about seven productive years, from 1982 to 1989. During a press preview none of the art was yet labeled (it is now), which made cross-referencing largely impossible. But the topicality, coupled with a career whose tragic brevity didn’t allow for substantial formal development, creates a time warp that resonates with Haring’s aesthetic. His work repeatedly conjoins ancient history with enduring pop style.

Haring made uninflected linear drawings almost exclusively glyphs and pictographs, like Paleolithic cave art with an agitated urban edge. Drawing describes almost everything in the exhibition, whether executed with ink or paint on paper, hardware-store tarps, the occasional canvas or even a few clay jars. Haring was a graphic artist, through and through.

Even many of his sculptures, generally the weakest works in his prolific oeuvre, are composed of flat, two-dimensional planes of wood or steel that intersect so that they can stand up in three dimensions — the most rudimentary of structures. Others are drawn on commercially produced found objects, like cheesy fiberglass knockoffs of the Statue of Liberty or a Corinthian column, suitable as low-budget Greek or Italian restaurant decor. Drawing is the most conceptually immediate of mediums, barreling straight from brain to hand to sheet; but Haring’s often cumbersome sculptural forms visually slow down the propulsion that keeps his best work surging.

Some of it is slyly funny, if thin, like the occasional invocations of New Age pyramid power. One clever painting shows a pair of adjoining cobalt-blue triangles visually vibrating against a tangerine ground, crowned by an explosion of radiating brush marks. The diamond shape, painted on a round Formica tabletop, shifts between describing a pyramid and a politely folded napkin. Another work adds flying saucers hovering nearby, a satirical nod to the pseudoscientific shtick of an ancient Egyptian empire built not by enslaved human beings but by aliens arriving in UFOs.

Haring’s images, like his self-portrait, often productively embrace internal contradictions. Take his famous barking dog. The brisk contour drawing of a boxy torso, snout and limbs all topped by a pair of pointy ears records an animal that is at once a human’s best friend and a menacing symbol of authoritarian power.

One of two cartoon-like panels in a large work in ink on parchment shows figures racing away from a dog yapping at their heels. The other panel shows figures energetically leaping over the barking beast, its growling threat shown to be ineffectual. Barking dogs seldom bite, as the saying goes, and Haring pictures the virtue of robust resistance to intimidation.

A work such as this reflects the two artists arguably most important to Haring. Walt Disney brought the madhouse of cartoons to a high level for mass consumption. And the snarling attack dogs recall the shocking Birmingham news photographs, taken by Charles Moore, that Andy Warhol turned into silkscreens to make his “Race Riot” paintings.

“Haring, Warhol, Disney,” an important 1992 exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum, traced those influences, which the artist acknowledged directly in paintings that feature an eccentric figure sporting Mickey Mouse ears protruding from beneath Warhol’s wild wig. Tellingly, the jaunty hybrid figure, dubbed Andy Mouse, also models the chunky, black-rimmed eyeglasses Haring wore. These pictographs, like the smiley-face caricature, are self-portraits too.

The Broad exhibition’s subtitle, “Art Is for Everybody,” was a Haring mantra, and it represents both a strength and a limitation. Art isn’t actually for everybody; television is — television, Hollywood movies, subway ads and every other ingratiating form of commercial popular culture, which is a dazzling hallmark of our age. The title’s sentiment needs tweaking. Art is not for everybody, it’s for anybody — which isn’t quite the same thing. Art is for anybody who wants it, which makes the viewer into an engaged and willing partner.

At any rate, social media has already seen sardonic comments posted about how the Broad’s art-for-everybody show is only for those with $22 to buy a ticket, a significant but different matter. The wide-open generosity of spirit in Haring’s vivacious work likely owes something profound to having come through life’s trials in an often cruel and deeply repressive society, white and patriarchal. A full embrace of his socially conscious identity is central to his being, as this deft show underlines.

It’s Keith Haring, gay man and artist, who is for everybody, in other words, whether or not his art is. That’s an egalitarian commitment ideal for celebrating during LGBTQ+ Pride Month — and every other one.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.