Review: Do you see the smile? Why Sanford Biggers' painting will put one on your face

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you look at a painting and smile, it is disconcerting to suddenly realize that the painting is smiling back.

Did one subconsciously induce the other?

This pleasantly perturbing exchange happens more than once in “Sanford Biggers: Codeswitch,” the fine traveling survey from the Bronx Museum of the Arts of paintings from the last decade by the Harlem-based artist, currently at the California African American Museum. Biggers’ skillful interactivity is one engaging leitmotif in the show.

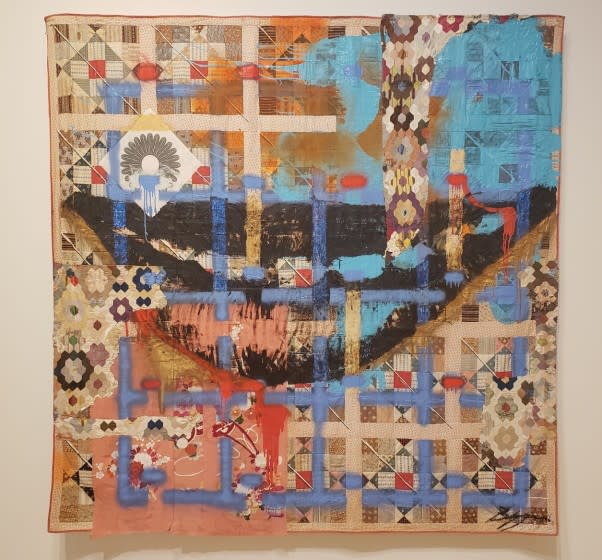

The first big smile — more of a sly grin — is in the first room, painted in thick, textured black almost edge-to-edge across a surface not of canvas but an antique quilt. Like Faith Ringgold, who began fusions of quilting and painting in the 1980s, Biggers cross-references the two.

This hovering smile is not a riff on the famous Surrealist “floating lips” of Man Ray. Instead, it recalls the one that’s a focal point of “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,” the little black-on-black painting of a gap-toothed smile that in 1980 launched Kerry James Marshall onto a productive revival of the long-dormant genre of history painting, which he centered on Black American life.

It’s also part Cheshire cat. The disembodied remnant of a now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t creature of elusive, discombobulating whimsy, the Cheshire grin represents unavoidable worldly madness.

On top of the grin, Biggers spray-painted a grid in light blue, visually stitching together a painted geometric pattern with the pieced squares of the domestic quilt. The contradictory use of a soft, drippy spray technique to render a firm, upright grid pattern suggests the public improvisations of graffiti.

The gesture is simple but determined: The relationship between the image of a grid and the quilt signals an artist in conversation with painting as a material object, one destined for a public rather than private life.

The same light blue paint is applied like spilled clouds of ethereal color in brushy, runny patches in the upper right corner. The baggy, flowing form runs counter to the grid’s brisk geometry. This loose, organic element underscores a quilt’s ordinary functional use as a bodily cover, different from the rectilinear convention of a squared painting meant for hanging on the wall.

One bracing aspect of Biggers’ art is its firm refusal of an unproductive hierarchy often attached to quilts. When the bold, brilliant quilts made by Black women in the tiny town of Gee’s Bend, Ala., took the art world by storm 15 years ago, it was often because of misguided claims about their similarity to Modern abstract paintings. Hanging the quilts on the wall, when they’re meant for a rumpled bed or neat folding in a drawer, easily obscures the lively, improvisational experience that yields the compositions’ actual power.

Biggers doesn’t make quilts that are “like paintings.” He makes paintings, and they are constructed from quilts.

The common bedding, almost 6½ feet square, is a size roughly repeated among a majority of the 40 paintings in the show. The scale makes a direct address to a viewer’s physical presence, body to body.

For “Hat & Beard,” Biggers also sewed red fabric rectangles onto the corner diagonally opposite the brushy blue, adding his own cloth pieces to an already pieced coverlet made by an unknown quilter sometime in an unmarked past. (His quilts are antiques, but nothing special.) Soon, you notice other added pieces of quilting — notably a scattering of six-petal geometric flowers that are a variation on a traditional pattern sometimes called a “Dresden bloom.”

One flower is a stark anomaly: Biggers designed an abstraction of a lotus, a single example of which he planted on the smile’s lip.

A lotus is a Buddhist symbol of purity and enlightenment able to emerge from murky waters. This one encompasses both illumination and gloom: Its radiating petals are formed from the notorious 1787 British drawing that shows the cross-section of the hold of a slave ship, filled to capacity with African bodies destined for the Americas.

Runny red paint sliding down through the smile can’t help but suggest blood.

The painting’s title, “Hat & Beard,” resonates with an admired 1964 tribute of that name to Thelonius Monk, recorded by jazz musician Eric Dolphy (born, like Biggers, in L.A.). The painter’s layered rumination is at once sorrowful and joyous.

Biggers also works in other media, including sculpture and projected video. A horizontal platform low to the floor in one gallery is the screen for a projection of fantastic break dancers on a brightly painted stage. Shot from above, the dancers’ thrilling windmills, head spins and hand hops seem otherworldly.

The format is like a hip-hop Buddhist mandala — an abstract landing strip for the earthly arrival of celestial deities.

Still, the show’s focus on quilt paintings is revealing. The original quilters’ race or ethnicity is likely unknown. But recycling found objects has been a hugely important tradition in Black art since the 1960s. Biggers approaches these antique quilts as tangible objects with authentic if anonymous histories, not simply as immaterial pictorial images.

He builds from there. Sometimes the result is a painting that becomes a wall relief.

The stacked, radiating square quilt pieces in “Kubrick’s Rube,” for example, are related to a traditional pineapple quilt pattern. The artist pushes the pattern all the way into three dimensions to become a stepped construction of stacked cubes jutting out from the wall. Think Frank Stella in the sewing room, rather than the industrial workshop.

Installed in a gallery corner, “Kubrick’s Rube” even recruits the adjoining walls as the next logical step in the cubic format — from quilt to painting to room. The architectural environment in which you’re standing gets surreptitiously enlisted in the aesthetic conversation.

“Reconstruction” is a wall relief made from cutting up more than one quilt, then sewing the pieces back together. They’re stretched within a gilt-edge structure whose angular, protruding shape is reminiscent of the folded planes of Japanese origami.

To make it, Biggers cut out linear strips of red and white fabric, plus white stars on a navy-blue field. He then reassembled the pieces, inserting pretty patches of floral motifs into the jagged bunting, to suggest fractured American flags.

The flag-waving design of “Reconstruction” is somewhere between a stylized origami landscape of peaks and valleys merged with ominous weaponry — a stealth bomber, say, or the sharp blades of a ninja star. The art object is sharply reconstructed quilting, with all the conflicted social ramifications of America’s failed 19th century history of Reconstruction.

Throughout the show, there’s a sense of these additive moves being made up as the artist went along, rather than following a predetermined design. They radiate pleasure in the making — a smile that reverberates in manifold ways.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.