Revisiting the Zachary Taylor encampment, and a missed opportunity for Corpus Christi

At 9:15 a.m. on April 16, the Greyhound bus pulled out of the station on Leopard Street and headed to Harlingen. The weather was pleasant promising a comfortable ride ahead. I had chosen travel by bus in order to relax and conduct research on my Samsung phone.

I marveled at the view of the new bridge, as the bus pulled onto Interstate Hwy. 37, whose construction issues have been recently resolved between TxDOT and the contractor.

This project, so vital to the Corpus Christi economy and its position nationally and globally, is on track again. The Port Industries are after all what connects the city to the world.

But the nature of my trip was to take me back in time. An announcement of a lecture at the Rio Grande Valley Hispanic Genealogical Society in Harlingen was to focus on the Palo Battlefield National Battlefield Historical Park, located 30 minutes south.

The park is part of the National Park Service, a successful operation and worth a visit.

I had attended the groundbreaking ceremony for the visitor center in 2002 at the request of Ed Harte, former Caller-Times newspaper publisher, who had offered a million dollars to develop a historic site marking the Zachary Taylor encampment site in Corpus Christi.

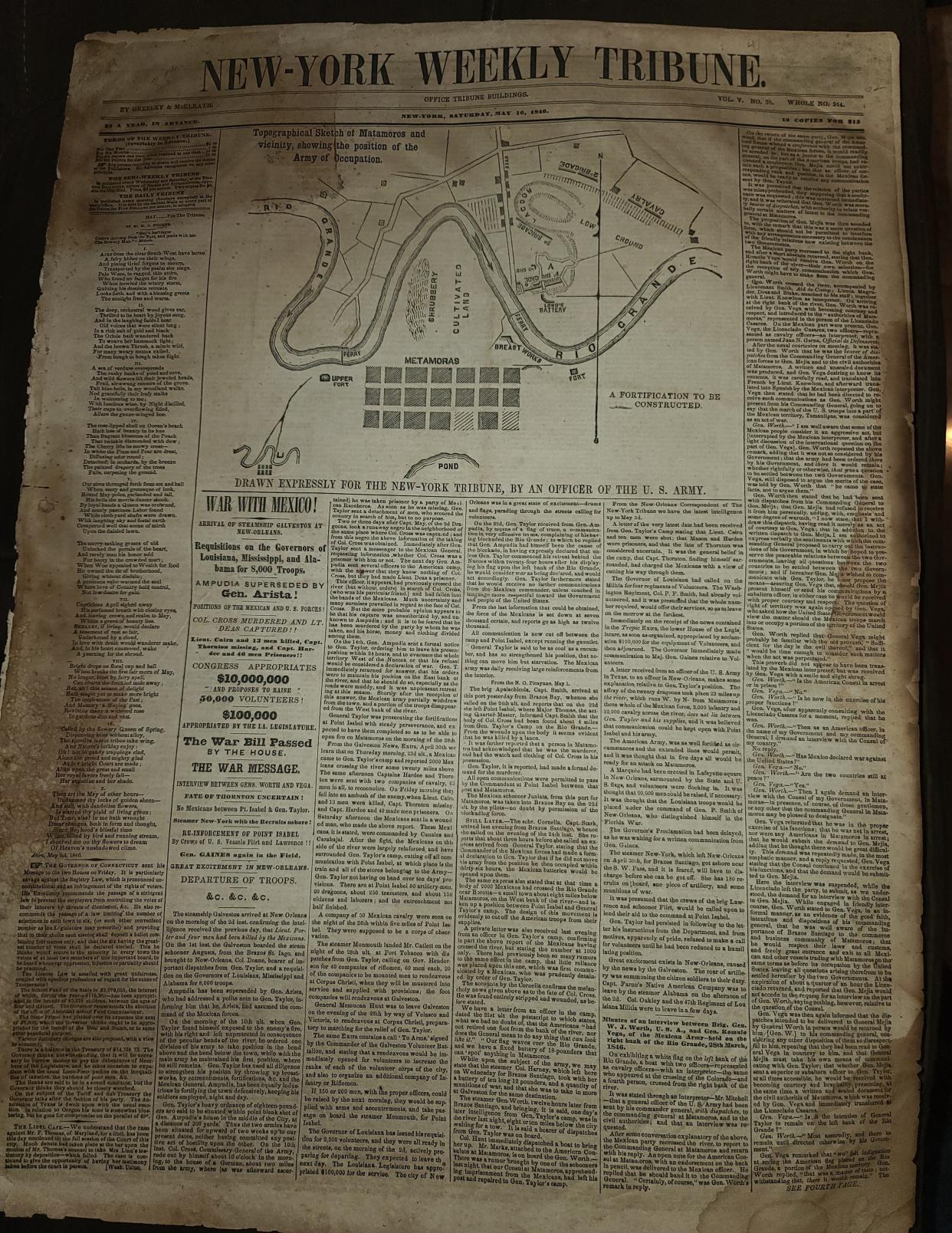

Taylor’s army spent some seven months here beginning in July 1845, training and waiting for orders. Those would come and a war between Mexico and the United States would ensue in May 1846 at present day Brownsville.

The outcome would change the destiny of the Mexico and the United States – extending the young republic to the Pacific and setting the stage for U.S. dominance on the world stage in the next century.

Corpus Christi took its place on the map – being incorporated in 1852. In short order it would pursue “deep water,” culminating in the establishment of the port in 1926, now one of the largest in the nation.

But alas Harte’s gift was pulled back amid opposition from a small group. Brownsville welcomed the historical park and reaps the benefit of added tourism.

Being frank, Corpus Christi blew it, and lost one million dollars, for starters, for what would have been a real impetus to downtown redevelopment.

I was eager to hear the park ranger. As it turned out she did not show up. But I stepped up and presented a program, off the cuff, focusing on the contrasts between Corpus Christi and Brownsville.

My talk was well received. The audience was engaged. None spoke in opposition to the historical park.

I was proud to have been able to present and to revisit an issue I am still committed to. On the personal level, I have collected material on the war, particularly newspapers of the day. It was the first war that newspapers covered in a major way.

I must recognize the late CPA and local historian Dan Kilgore who got me started in studying local history.As president of the Nueces County Historical Society I was honored to have led the organization to establish an annual local history awards ceremony in Dan’s memory.

Because of Dan I was prepared when Ed Harte asked for my help. God rest their souls.

Herb Canales is a fifth-generation Corpus Christi resident. He served as the city of Corpus Christi's library director for 27 years.

This article originally appeared on Corpus Christi Caller Times: Revisiting the Zachary Taylor camp, and a missed opportunity for city