Rhode Island's housing crisis is at a breaking point. How did we get here?

WARREN – The residents of these quiet side streets east of the Kickemuit River answer their doors when you knock and welcome strangers – unless they're trying to build 40 apartments in a field next door.

Then they will band together, sticking red-lettered signs on the front lawns urging people to "Stop Penny Lane," an affordable housing development and the latest battleground in Rhode Island's housing wars.

"To develop and change our neighborhood is just wrong," Joan Hunt, a neighbor opposed to Penny Lane told the Warren Planning Commission at a recent hearing. "We are a small coastal community, not an urban one."

Rhett Nanson, another neighbor, was more blunt.

"The ruse of affordable housing ... is just a lie: no one aspires to get an apartment unless you still live in the Soviet Union," he said. "What is the point of having guidelines if we are going to ignore them? I thought the purpose of them was to keep us from becoming an urban hellscape."

In Rhode Island, resistance to change clashes with efforts to boost affordable housing

Opposition to new construction is a common sentiment in communities across Rhode Island, a state not known for embracing change.

But as the housing shortage has become a bigger problem for more Rhode Islanders, resistance to building new places to live conflicts more and more with efforts to make places to live actually affordable.

Home prices, whether you rent or buy, are higher than ever. Housing options are scarcer than ever.

Take the houses around Penny Lane, for example.

When they first went on sale in 1985, you could buy one of the raised ranches on Fern Drive for $65,000. Now, they go for half a million, if you can find one on the market. A recent search turned up only one house listed in the vicinity, a small Cape-style home close to Kickemuit Middle School with an asking price of $470,000.

This newfound exclusivity is an uncomfortable fit for Warren, a quirky town with a working-class history and left-leaning politics.

A walk west from Penny Lane takes you past a bowling alley, some empty storefronts and a few tightly packed 19th-century apartment houses before you get into the center of town.

It might not look like neighboring Barrington, which is known for its affluence, but it's not far from being that expensive.

Less than 4% of Warren's housing stock is considered affordable under the state low-income housing law designed to encourage communities to get to 10%.

And yet at the start of this year, the Warren Planning Commission effectively sided with neighbors like Hunt and Nanson, refusing to allow Penny Lane unless the 40 planned units were sliced to 25, a change its nonprofit developer said would be a nonstarter with RI Housing.

That decision – which may have have run afoul of state law and could soon be reversed – came after the town last year rejected an apartment building with affordable units proposed for Water Street.

Penny Lane's developer, East Bay Community Development, had to go to the state Supreme Court in 2006 for permission to build a similar 47-unit affordable townhouse project called Sweetbriar in neighboring Barrington.

New construction is so controversial in Barrington that even though the town spent $3.2 million to buy the former Carmelite Monastery there, neighborhood opposition to building almost anything has kept it unoccupied and decaying.

And over in Tiverton, the town has put a six-month moratorium on residential development proposals of more than four homes.

The East Bay might be the current poster child for not-in-my-backyard versus yes-in-your-backyard conflict, but it is hardly unique.

For years, Rhode Island has ranked last or close to last in the country for per-capita new home construction.

In its report on housing for the Rhode Island Foundation last year, Boston Consulting Group calculated that Rhode Island was 50th in the nation for adding new housing units per capita in 2021.

The Journal crunched census data for 2022, the most recent now available, and found that Rhode Island had moved up to third lowest per-capita, behind New Jersey and Illinois.

By another measure, the number of new home's approved for construction, the Ocean State was again 50th per capita last year. The number of units approved by local officials in Rhode Island last year fell for the third consecutive year to the lowest level since 2017, based on the Census Bureau's building permit survey.

Housing safety net is hanging by a thread

Soaring home prices and rents, combined with meager inventory of housing options, have made it harder to move to Rhode Island, move within Rhode Island or start a family here, even for those with a job.

And it has grown the share of Rhode Islanders for whom homeownership is out of reach, and finding anywhere to stay is a constant fight for survival.

The state's housing safety net strained last year as the number of Rhode Islanders living in tents, cars and emergency shelters, or sleeping on couches and sidewalks, grew to more than 1,800 people, a 72% increase since 2019, according to the Rhode Island Coalition to End Homelessness. Over that period, the number of people without any form of shelter rose from 71 to 334.

State leaders have belatedly moved to expand shelters and fund new low-income housing options, but progress has been slow, challenged by local opposition and unexpected setbacks. If the number of people living at the financial margins and priced out of the market keeps rising at this rate, government programs may never catch up.

The number of single-family houses sold in Rhode Island last year fell 22.5% to the lowest level in a dozen years, according to the Rhode Island Association of Realtors.

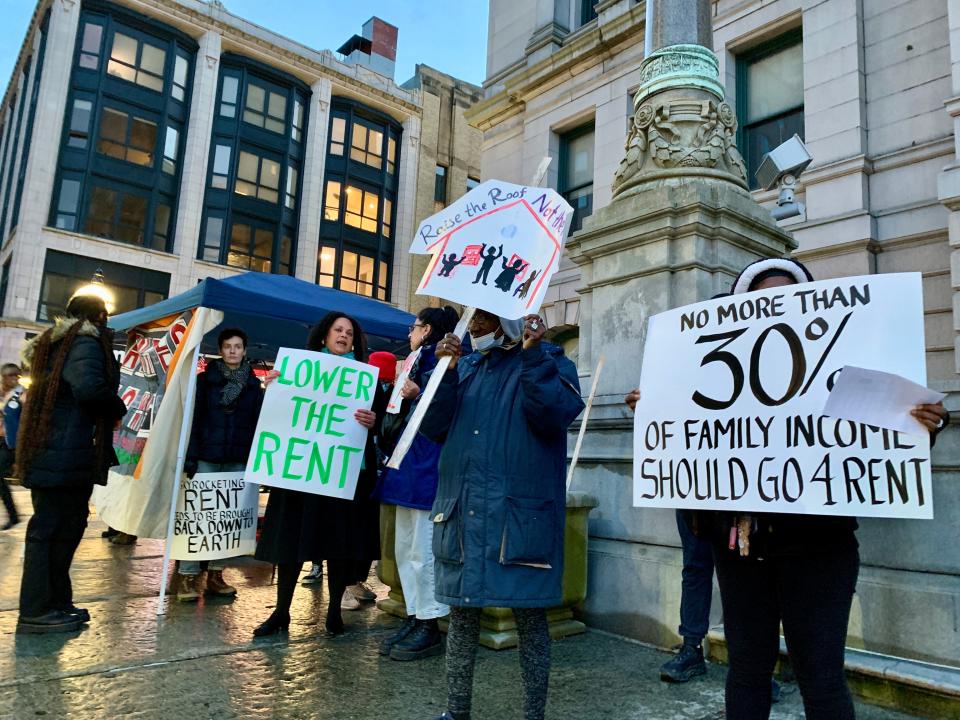

The rental market may be even tougher. The median rent (including all bedroom types) in the Providence metro area in November was $2,846 per month, according to Rent.com. That's a 22% increase from a year ago, the biggest hike in the nation.

Zillow reported that Providence posted the highest year-over-year rent increase for both single family and multifamily homes in November, up 9.4% and 6.9%, respectively. (In the same month, Hartford and Boston posted the second-largest annual multifamily rent increases – 6.5% and 5.6%.)

Putting radical options on the table

Because affordable homes have become scarce for all but the richest Rhode Islanders, solutions once considered radical are now on the table.

They range from boosting already record state spending on construction subsidies, to allowing apartments in single-family neighborhoods to instituting rent control and even building new publicly owned housing.

For most of these solutions to work, some Rhode Island neighborhoods will have to change, at least a little.

Seth Zeren, a principal at Armory Management Company in Providence and co-founder of housing advocacy group Neighbors Welcome RI, said the state can easily improve its anemic 0.29% annual housing stock growth without radically changing neighborhoods.

"We need to get to at least 1% annual growth. And every city, town and neighborhood can and should do its part," Zeren said. "In a neighborhood of 100 homes, 1% growth means each year there's just one new [Accessory Dwelling Unit] townhouse, or small lot home. That's not a drastic transformation."

How did we get here?

Rhode Island industrialized through the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, with waves of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, French Canada, Cape Verde, Portugal and elsewhere arriving to work in the growing mills while the Great Migration brought Black Americans from the rural South to the North in search of jobs and opportunity.

Apartment houses, including New England's famed triple-deckers, sprang up to shelter the new arrivals. But with the urbanization of Rhode Island's cities came a backlash.

By the 1910s, a movement to slow urban growth, or at least prevent it from encroaching on the best neighborhoods, was gaining momentum.

New York City enacted the nation's first zoning ordinance in 1916 to, as a Journal editorial that year put it, encourage the "lateral spread rather than ‘capitalization of the air,’" in cities.

The idea quickly spread.

In November 1920, Flavel Shurtleff, secretary of the National Conference on City Planning, explained the concept to a gathering of Providence business leaders.

"The purpose of zoning is the same as the purpose of restrictions in deeds to high-class residential property," Shurtleff said. "The house must cost $6,000, it must be set back 20 to 40 feet from the property ... no stores, factories or public garages [may] be built in the neighborhood."

The General Assembly authorized cities and towns to create their own zoning codes in 1921, and, after a lengthy process led by consultant Robert Whitten, Providence enacted its first code in 1923.

In addition to banning commercial activity from residential neighborhoods, the zoning code also aimed to "decentralize" development, as Whitten put it, and spread it out.

As the automobile took over transportation in the decades that followed, the crusade to spread communities out accelerated with city planners demanding that homes sit on ever-larger lots with fewer units on each lot and more space reserved to park cars.

More: 'Traumatic': How Route 195 uprooted the Cape Verdean community in Providence's Fox Point

Soon, large swaths of the downtowns and historic sections in most Rhode Island communities were "nonconforming," or illegal, under local zoning codes.

With existing buildings "grandfathered" if they predated the codes, mid-20th-century planners turned to urban renewal, slum clearance and highway construction to knock down many low-income neighborhoods that didn't conform to the new suburban ideal.

The historic-preservation movement emerged to save some classic Rhode Island neighborhoods, but generally not if they were poor.

Growth of the Rhode Island suburb starts with Garden City

By World War II, the growth of Rhode Island's cities was over, and a new building boom emptying them into the suburbs had begun.

Starting with Garden City in Cranston, builders rushed to meet demand for more and larger homes, gobbling up land and pushing into the countryside.

As of 2021, 43% of all residential structures in Rhode Island were built between 1940 and 1979, according to data from HousingWorks RI.

Construction was strong through the 1980s, but concerns about the environmental impact of suburban development grew, resulting in a series of State House battles between homebuilders and conservationists.

In 1992, the General Assembly passed its last major zoning law rewrite before last year's pro-building reforms. It standardized many local zoning processes for builders while creating new environmental rules, including limiting development near wetlands.

Building boom and bust

In 1986, Rhode Island municipalities approved permits for 7,274 new housing units, according to census data. Over the following two decades, they were approving an average of around 2,500 units per year, the overwhelming majority of them single-family, before the housing bubble burst in 2008 and almost everything ground to a halt.

By 2011, the number of units permitted plunged to 700 before rebounding to around 1,300 per year in recent years.

Rhode Island has added around 40,000 new residents over the last decade, nearly twice the number of new homes over that period.

And that doesn't take into account the homes taken out of the permanent housing supply by everything from neglect to fires, floods, airport runway extensions and conversion to short-term rentals.

Since the COVID pandemic, demand for residential space has soared as people have left the office and sought more space at home for remote work and leisure.

Younger adults moved out of their family homes and ditched roommates, while older Rhode Islanders aged in place after the rest of their family moved out.

As a result, as houses get bigger, the number of people living in each one gets smaller, increasing the number of homes needed.

The number of households in Rhode Island increased 8.3% from 2018 to 2021, according to the Boston Consulting analysis for the Rhode Island Foundation, outpacing population gains.

Why does it take so much time, and money, to build affordable housing?

In June 2022, Olneyville-based affordable housing developer One Neighborhood Builders identified a decrepit 1970s building surrounded by parking lots on Taunton Avenue in East Providence as a promising site to build apartments for Rhode Islanders at risk of homelessness.

Working with social service providers Foster Forward, Crossroads Rhode Island and Family Service of Rhode Island, One Neighborhood bought the properties, designed a three-building complex and guided it through local permitting in East Providence.

But a year and half later, with $6.4 million already spent, One Neighborhood still doesn't know if the Center City apartments will be built.

The developer is waiting to hear whether its financing will come through, with a decision expected in May. Even if it does, a shovel is unlikely to hit the ground on Taunton Avenue until sometime in 2025.

Last fall, One Neighborhood president and CEO Jennifer Hawkins, who is also a member of the Rhode Island House's Affordable Housing Study Commission, presented Center City as a case study to her fellow commissioners on why, despite an unprecedented state investment in affordable housing over the last two years, it takes so long and costs so much to build affordable housing.

First, East Providence, one of the more development-friendly cities in the state, sliced 26 apartments off the proposal during the permitting process, reducing the number of units that would be producing rent to pay for the construction.

Then, city planners ruled that the development, which has a RIPTA stop at the front door, did not have enough parking spaces, so a planned child care center was canceled.

But One Neighborhood and Hawkins pressed on, looking for funding and ways to make the smaller $64 million development work.

"So this is how we're going to pay for it, and if your mind explodes, I can understand that," Hawkins told the commission while showing a slide with all the different sources Center City is relying on for financing. "There's 21 different and prospective sources that we are cobbling together. Our capital stack, as they say, is like a very, very tall leaning tower of Pisa."

The sources include a federal earmark, six different pots of American Rescue Plan money, grants from several private charities, local Community Development Block Grant funds, state housing bond money, a mortgage from Rhode Island Housing and, the largest source, the proceeds of federal tax credits sold to private companies for around 90 cents on the dollar.

The inherent uncertainty of pasting together 21 funding sources, and the amount of time needed just to launch a development, adds to the cost. And then there are a host of middlemen taking a cut.

"The accountants and attorneys make a huge amount of money on brokering these deals. And also there's a syndicator. There's a middle person between the investor and the developer that we have to rely on, and they, of course, make a cut," Hawkins said in response to a question about whether the current tax credit system subsidizes corporations. "There's a lot of layers of grift, if you will."

Some of these costs might not have been as noticeable a decade ago, but as construction costs have skyrocketed, insurance premiums have soared and interest rates have climbed, the amount of housing-per-public dollar spent has fallen.

The two dozen projects approved in Rhode Island Housing's most recent funding round had an average per-unit cost of $400,000, and that included some projects that are renovations of existing buildings.

Some developments are even more expensive. The conversion of three former mill buildings in Woonsocket into the 70-unit Millrace apartments is expected to cost $40 million. That would be $570,000 per apartment, although the project also includes commercial space. The residences alone cost around $405,000 per unit, according to Melina Lodge of the Housing Network of Rhode Island.

The business-backed Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council estimates that, at current costs, the $100-million bond that Gov. Dan McKee has proposed – which would be the state's largest ever – would produce only 823 new housing units, if all of it were dedicated to production. (Typically, only part of a housing bond pays for new construction.)

The public-private financing system does have its advantages and was developed as an alternative to the government-run public housing developments of the 20th century, which became poorly maintained and stigmatized.

"It allows for private money to come into a project, and it makes for a bigger tent of advocates who are championing affordable housing," Hawkins said. "And I think that it's really important to have private sources involved in the program."

Penny Lane may rise again

Back in Warren, neighborhood relief that Penny Lane had been stopped, or chopped down to size, might have been short-lived.

A law passed by the General Assembly as part of House Speaker K. Joseph Shekarchi's housing agenda last year allowed qualifying affordable developments in communities like Warren to build 12 more homes per acre than would normally be allowed under local zoning.

For Penny Lane, that would mean 54 units, more than double the number the Planning Commission wanted, and even more than the developer was proposing. (The original plans called for 14, two-story townhouses with a mix of one, two and three-bedroom units.)

Facing a potential lawsuit, the Warren Planning Commission is set to revisit its decision Feb. 12.

Next door to the prospective construction site, residents like retired Navy veteran Richard Almeida are worried about drainage problems from new construction and that tenants of the new development won't maintain their homes.

"I'd be OK if they put [in] half a dozen houses, but when you see the picture of it, that's a lot of buildings there," Almeida said.

A few doors down, retired insurance claims adjuster Sue Machado says she doesn't object to some homes being built, but anything new should look like what's already there.

"We're not against affordable housing. It is just how big it is going to be," said Machado. "Why don't you just turn it into another cul de sac. Ten houses. Putting all that there is just a little extreme."

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Rhode Island is in a housing crisis. It took decades to get here.