With Richard Noble Out of the Game, Has the Car Reached Its Speed Limit?

From the August 2020 issue of Car and Driver.

The desire to do better lies at the heart of humanity's progress, from animal skins to Gucci loafers, rock-hewn cave art to boastful Instagram selfies. As a species, we strive for improvement, always. And with every record comes an implicit challenge to beat it, whatever the cost.

Richard Noble knows this all too well. He has lived most of his life in pursuit of the world land speed record (LSR), which is exactly what it sounds like. Attempting the LSR has always been a risky pursuit—Noble's new book is called Take Risk! for a reason—and yet, even when he attained it, the man still wasn't satisfied.

His obsession with the LSR began in his teenage years in the mid-'60s, at a time when the record sometimes lasted mere days. But then the pace of one-upmanship slowed. And after Gary Gabelich's rocket-powered Blue Flame reached a remarkable 622.407 mph at Utah's Bonneville Salt Flats in 1970, it seemed to come to a stop.

Noble built his first jet-powered car while working as a building-supplies salesman, with much of the work done in a suburban garage. Thrust 1—an entirely deliberate double-entendre—combined a truck chassis with a military-surplus Rolls-Royce Derwent jet engine. Noble crashed it at about 140 mph during an attempt to set a British speed record in 1977. "We think a wheel bearing failed," he says. "It just went, the car spiraled in the air, and of course the fundamental problem with a jet car is that it keeps [accelerating] even if the wheels have left the ground." He survived the wreck unscathed, sold the remains to a scrap merchant for about $300, and immediately began to plan his next car.

Thrust 2 was bigger and more serious, with the critical difference being the arrival of engineer John Ackroyd, who designed the car. "I'm not an engineer," Noble says, "and I designed and built Thrust 1, which was thoroughly dangerous. John brought the discipline and engineering experience and knowledge."

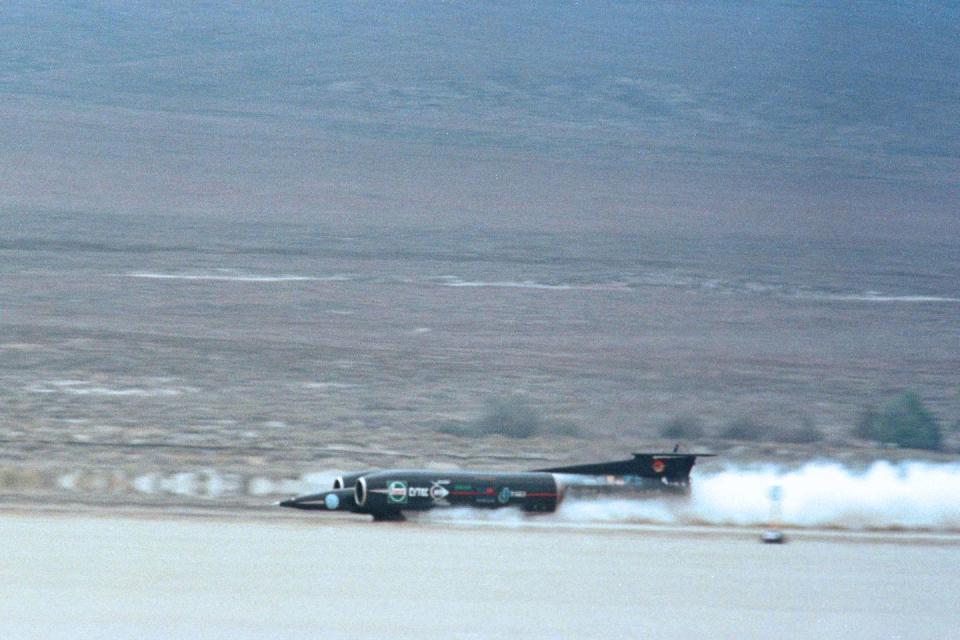

During a test at an airbase in the U.K., Thrust 2's braking parachute failed and Noble survived another crash. The resulting 4000-foot skid mark may have been a record in its own right. Not discouraged, the team repaired that car and Noble drove it to a history-making 633.468 mph in Nevada's Black Rock Desert in 1983, beating Gabelich's 13-year-old mark by 11.061 mph.

While designing and building Thrust 2 was hard work, Noble remembers the battle for funding as even more difficult. "We've got a real problem in Britain, which is that we are totally and utterly risk averse," he says. "There's always been that argument: Why on earth sponsor a car like that? Because it might just crash, and the last remaining bit of the car would have your logo on it."

Thrust 2's record still stood when Noble decided to aim for a more ambitious goal. Inspired in large part by five-time LSR holder Craig Breedlove's plans to build a supersonic car, Noble set out to break the sound barrier with Thrust SSC. He relinquished driving duties to Royal Air Force wing commander Andy Green.

Money remained the problem, with the team lacking the funds to fuel the plane that was to fly the finished car to Nevada. "I needed about £100,000 [$160,000] worth of fuel, and nobody was going to help," Noble says. "And of course Breedlove was already out in the desert and telling everybody we weren't going to make it. One guy on our team, Jeremy Davey, had this brilliant idea of setting up what was effectively the world's first internet crowdfunding operation. We just wrote the software one night and banged it up. Suddenly, we had £150,000 [$240,000] for fuel the next morning. People all over the world wanted us to do it."

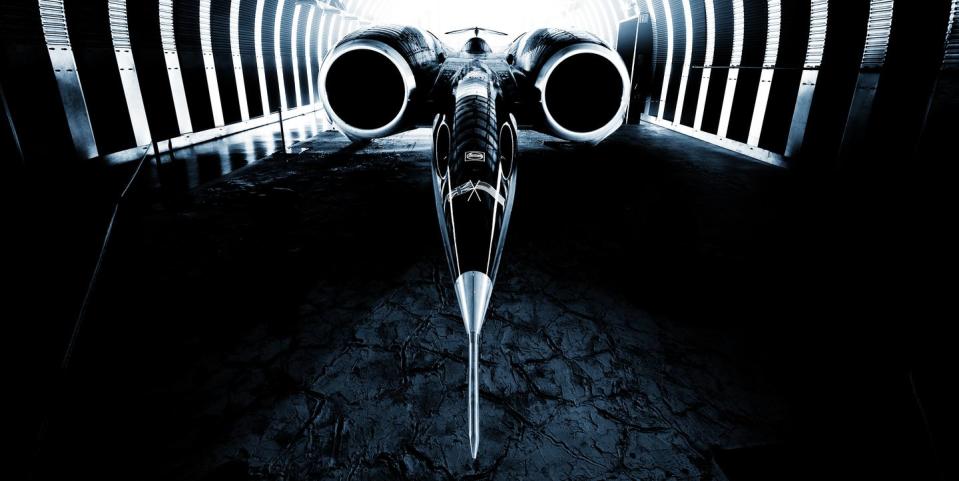

Thrust SSC set both subsonic and supersonic LSRs in Nevada in 1997, first reaching 714.144 mph and then 763.035, but Noble and Green were determined to do better. Their next venture, called Bloodhound SSC, aimed to push the record to 1000 mph. Noble persuaded the British government that the car could help advance science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education in the U.K. Indeed, the Bloodhound project has inspired STEM initiatives wherein kids learn about things such as Newtonian laws with model rockets. So with the government on board with the project, Rolls-Royce allowed the loan of its state-of-the-art EJ200 jet engine, the same found in the Eurofighter Typhoon.

Reaching 1000 mph brought new challenges, namely the additional cost and complication of rocket assistance. Work on Bloodhound began in 2008, with high-speed runs scheduled to begin in 2011. That didn't pan out. In 2012, Noble told Car and Driver that the team was aiming to complete these runs by 2014. Then and now, Noble candidly admits the problem was the familiar one: money.

"It's a big project to produce a supersonic vehicle, the same really as making a supersonic airplane, and somehow you've got to keep the cash coming in," he says. "Sponsors came and sponsors left. We had periods of three months or so where we had no money at all. We kept going. It was a terrific team, and they wouldn't give up."

Large backers, including Jaguar Land Rover, fulfilled their obligations and then dropped out. Chinese auto giant Geely agreed to help, apparently at boss Li Shufu's personal insistence, but funding was contingent on British government support that didn't come. Noble says the U.K.'s lengthy withdrawal from the European Union diverted attention. In late 2018, the cash finally ran out for good, and Bloodhound entered administration (i.e., the U.K. equivalent of corporate bankruptcy). Entrepreneur Ian Warhurst purchased Bloodhound and funded a testing trip to South Africa, where the car ran at 628 mph under jet power. But without funds to pay for the necessary rocket development, the team has had to put the program into hibernation.

A few others have taken up the mantle but without success. The North American Eagle challenge ended in failure last year, with Jessi Combs's fatal crash in the Alvord Desert in Oregon. And Australian drag racer Rosco McGlashan is still working on the rocket-powered Aussie Invader 5R under the slogan "Comin' at ya, 1000 mph." Work began more than a decade ago but the car has yet to run.

Will the current LSR ever fall? Noble certainly hopes so but knows it's a long shot. "I spent 55,000 man-hours trying to break it," he says. "And it's all about money now. If Bloodhound fails, there may never be another one. You see, this is an incredibly difficult exam on a huge range of fronts—everything from project management to the motivation of the team, the finance, the engineering—done on a very, very small budget. It's a formidable thing to undertake."

Noble is no longer involved with any LSR attempt but regards them as a noble calling: "It's a kind of socially acceptable warfare, I think. That's the best way to describe it."

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos