How Richard Petty Was Shortchanged From NASCAR Cup Win No. 201

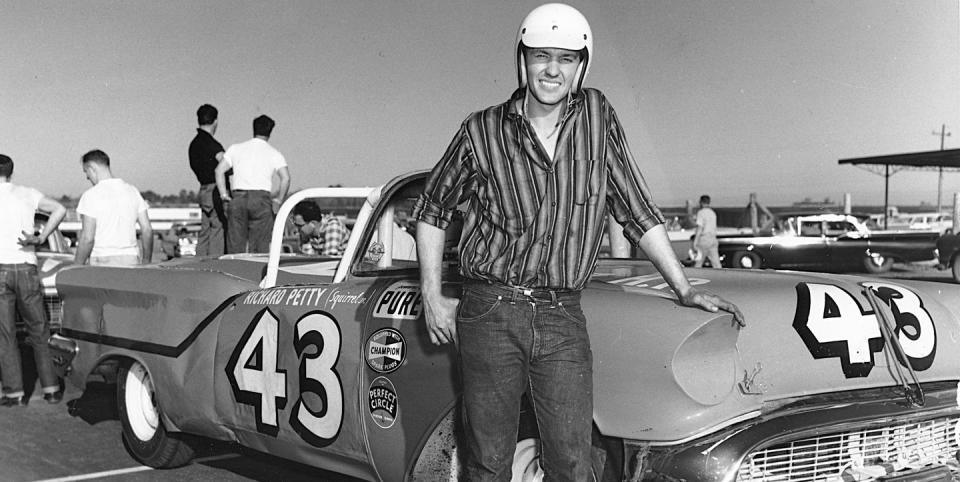

The record books say that Richard Petty's first of 200 NASCAR Cup wins came in 1960. Richard says that's not exactly true.

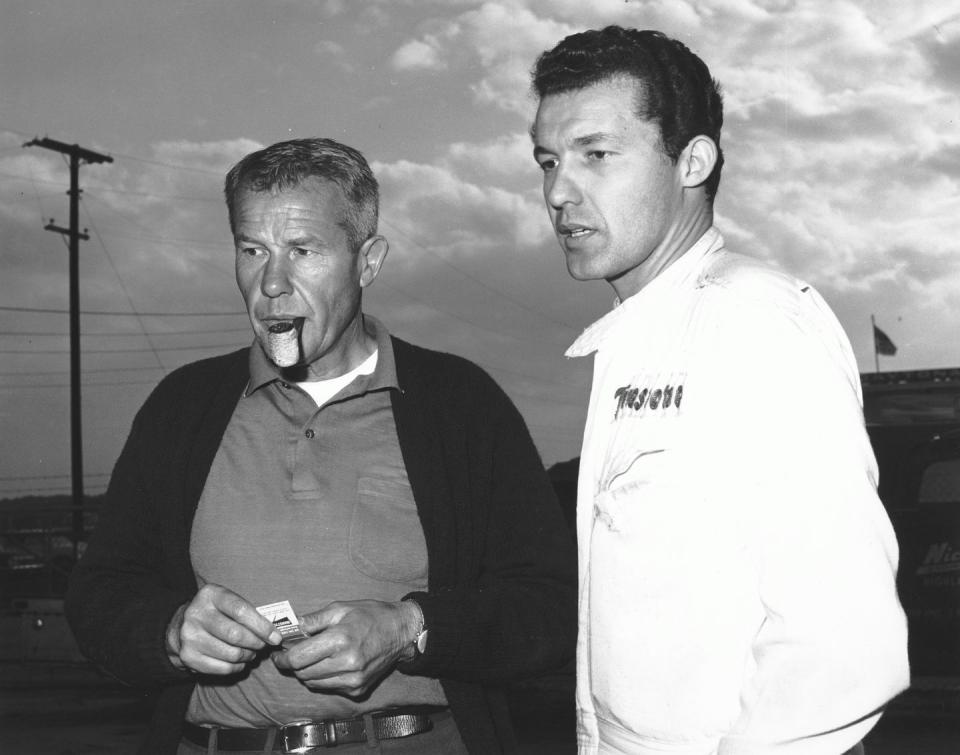

Richard's greatest rival in his early years in NASCAR was his father, Lee Petty.

Petty went on win a record 200 wins in 1,184 career starts in Cup.

Richard Petty would have retired with 201 career Cup Series victories if his father, Lee, hadn’t been so obsessed with money. Or maybe it was simply a matter of expressing his parental authority.

It happened like this:

In June 1959, at the 1-mile dirt Lakewood Speedway in an Atlanta suburb, Richard and Lee were flagged 1-2 in a 150-lap “Sweepstakes” race featuring convertibles and sedans. Moments after the checkered flag, Lee protested the result. He argued strenuously—every Lee Petty argument was strenuous—that he was first and his son was second. Their finishing order, he insisted, was backward and should be reversed. (There was no issue with the other top-5 finishers Buck Baker, Curtis Turner, and Tom Pistone).

Such disputes were commonplace when scoring was humans putting pencil to paper every lap. Now, with computer technology and transponders, errors have virtually disappeared. In this case, the protest was upheld after a lengthy review. Richard, just 21 but wise beyond his years, knew better than to protest the protest of what would have been his first victory. He knew money was important, and Petty Enterprises needed all it could get.

The Lakewood 150 entry offered an extra $250 if the winner drove a convertible … like Richard’s No. 43 Oldsmobile. It also offered an extra $450 if the winner drove a 1959 current-year model … like Lee’s No. 42 Plymouth. Lee did the math and realized his business would benefit by his winning. His bonus would beat Richard’s, and that $200 difference was serious money back then. Lee didn’t hesitate to take the money and the winner’s trophy.

“Second was the best I’d ever run, so I was still tickled to death,” Richard recently told Autoweek. “I was out of the car jumping around ‘cause I’d just won for the first time. Then, somebody came over and said Daddy had protested the scoring. Later, he explained that we’d made more money with him winning and we needed every little bit we could get.

“Really… it didn’t matter that much to me. I was just a 21-year-old kid happy to be there. All I cared about was that we had enough cars and money so I could keep racing. It didn’t make that much difference as long as the company came out ahead. In the end, I think the scorers got it right.”

The next day, in the Atlanta Constitution, a sportswriter quoted Lee: “Either way you look at it, we are 1-2. But I won the race; I lapped Richard twice when he was in the pits. He’s my boy and I would love to see him win a race. But when he wins one, I want him to earn it. This wouldn’t be the right way for him to get his first victory. I would have protested my mother if I needed to.”

A year before Lakewood, there had been Toronto, the first of Richard’s “official” 1,184 starts and the first of his 984 losses. Again, Lee was in the middle of things.

Richard’s debut was July 1958 in a 100-lap race at the third-mile paved Canadian National Exposition Speedway. Two weeks after turning 21—to Lee, that was manhood—Richard qualified seventh in the No. 142 Oldsmobile. He barely reached halfway before crashing out to 17th. Lee, pole-sitter in the No. 42 Oldsmobile, led the final 29 laps in beating Cotton Owens, Jim Reed, Shorty Rollins, and Johnny Mackison.

But there’s more to it than that. The flagman that day, an official named Ross Kennedy, blamed Lee for Richard’s crash. “Richard was all over the track,” he told journalist Mike Hembree in 2010. “Lee was leading, and he came around and there was Richard, in the way. WHOOMP! That was the end for Richard.” (Clearly, the elder Petty took no prisoners; not even his son).

Toronto was part of NASCAR’s annual mid-summer Northern swing. Richard skipped Busti, N.Y., then finished 17th in Toronto and 11th in Buffalo. He was a career-best ninth in Belmar, N.J. (the famous Wall Stadium) before skipping Rochester, N.Y. and Bridgehampton, N.Y. Even though one Southern journal had called him “a young sensation,” the future King’s career was off to a rocky start.

“Everything was Daddy’s deal about where we raced and when,” he explained when asked about running only half the six Northeastern races. “He said we were going to Canada, so we loaded up and went up to Canada.” As usual, he said all the right things: “It wasn’t much of a start for me,” he told reporters after crashing at Toronto in his first start, “but Daddy won, so it was good for the Pettys.”

The “young sensation” made eight more starts in 1958 and 21 more in his Rookie of the Year season of 1959 (among them, the disappointment at Lakewood). By the time he went full-schedule racing in 1960, he already had six top-5’s and 10 top-10’s in 30 starts. Clearly, the potential was there … if not the results.

That potential finally bloomed in February 1960 on the half-mile dirt Southern States Speedway near Charlotte. The 200-lapper was Richard’s 35th career start, the sixth on that year’s 44-race schedule, and the first since Junior Johnson had won the second annual Daytona 500 two weeks earlier.

Just 22 and still honing his skills, Petty qualified seventh among 21 entrants. There is controversy and confusion about the race, not least of which involves lap leaders, lead changes, contact, and intentional teamwork.

One version has No. 2 qualifier Rex White leading the first 182 laps while, reportedly, “Richard kept the leaders in sight.” Richard was second after 182 laps when (according Richard’s version) White hit a huge Turn 1 pothole and briefly lost momentum. That allowed Richard to pass cleanly and drive off to his first career victory. Two leaders, one lead change, and nothing particularly untoward.

Another version is that Lee, lapped and driving in relief of Doug Yates, simply knocked White aside in the final laps to make Richard’s winning pass easier. It’s unclear from race reports whether White and Lee spent the afternoon racing each other hard. It’s also unclear whether White so was dominant that Lee didn’t get close enough to hit him until late, when he was being lapped.

“Honestly, I don’t remember much about that race,” Richard said recently. “It was a long time ago. I do remember the track was unbearably rough, but not much else about what went on. There were potholes and bumps and ruts all over the place, and Rex got into one of them. I guess I got though the holes and rough spots better than he did. I think only about seven of us were still running at the end.”

The top-5 behind Richard and White were the lapped cars of Yates (no relation to Hall of Fame engine-builder Robert Yates), Johnson, and Joe Eubanks. In addition to the two Pettys, White, and Johnson, the 21-car grid featured future Hall of Fame drivers Ned Jarrett, Buck Baker, Cale Yarborough, and David Pearson.

White, now 91, well remembers Lee knocking him aside in the latter laps, ruining his chance of winning. “We’ll never know if I could have won,” he said from his home in western North Carolina. “But I certainly was in contention until Lee hit me. As much as I raced with Richard through the years, I never had any confrontation or disagreement with him. He didn’t do a thing to me that afternoon. But I didn’t get along with Lee, not one bit. And I wasn’t the only one that didn’t get along with him. No, sir.”

When asked about it afterward, Lee would tell a Charlotte Observer reporter only: “I didn’t hurt Richard’s chances.”

Was that a grin he was trying to hide?

After all these years, Richard’s numbers seem unfathomable: 1,184 career starts; 123 poles; 200 victories; 555 top-5 finishes; 712 top-10 finishes; 7 Cup Series titles and 18 other top-10 points seasons; 9 Most Popular Driver awards; 1959 Rookie of the Year; and (unofficially but unquestionably) the most important driver in the history of American stock car racing.

Even if he won “only” 200 times.

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos