Richard Serra Stuns Yet Again With a Blockbuster Trio of Gagosian Shows

An attractive, intelligent-looking woman sits at the front desk of Gagosian gallery on West 24th Street in New York City and sighs, not for the first time, as the doors swing open. “Serra opens at six,” she says, firmly, to those who ignored the two signs on the door telling visitors the same thing.

You might assume that, since this is fall in New York, these people are scenesters, eager to get into the big buzzy art shows first, just like into the new restaurants. But you’d be wrong. Watching the parade, the eagerness seems genuine—palpable. As the would-be crashers enter, they actually tilt in, as though if they could just whoosh by that vigilant gallerist, they’d be able to break free into the galleries, a black-clad army of sculpture fans thrilled that Richard Serra’s new art is in town.

Early this week, influential dealer Larry Gagosian opened Serra shows at a trio of his New York spaces. At 555 West 24th, there’s an installation of precise and defiant 50-ton steel cylinders, titled Forged Rounds; uptown at 980 Madison are two floors of drawings, Triptychs and Diptychs on handmade paper. The entire 522 West 21st Street gallery is devoted to a single, almost block-long, Serra artwork: Reverse Curve, a huge ribbon of rusty hot, rolled steel, glorious in its ambition and grace.

Three concurrent shows of new work at the ripe age of 80, plus a welcoming audience? Serra has the almost unheard-of distinction in the faddish, brutal art world of never having been out of the conversation, or “out” of fashion at all. He has never had to be "rediscovered." The Museum of Modern Art's website features 59 Serra exhibitions, or exhibitions that have included Serra, dating back to 1982. An even rarer distinction: MoMA has said they specifically beefed up their floors to carry the weight of Serra sculpture.

Across the U.S., from collectors Aggie Gund to Eli Broad, and internationally, the California-born, Yale-educated artist's work is everywhere. So how does an artist of persistent and widespread world success still manage to carry such a cult vibe?

Prescience is part of it, surely. In art jargon, Serra’s art is process art—art about how it's made, what it is made of, how those materials age and change, and how all that makes the viewer move and feel. Perhaps more simply put, Serra's art was “experiential” long before that word started appearing in every 21st-century tourism brochure to describe immersive, striking encounters. The art of Serra is what it does to you—how “it propels you,” says Gagosian senior gallery director Kara Vander Weg. In the past, Serra’s giant works have pulled people in with their elements of mazes or shelters, and there are hints this time around of steel graveyards, of hide-and-seek playgrounds, of forests to explore.

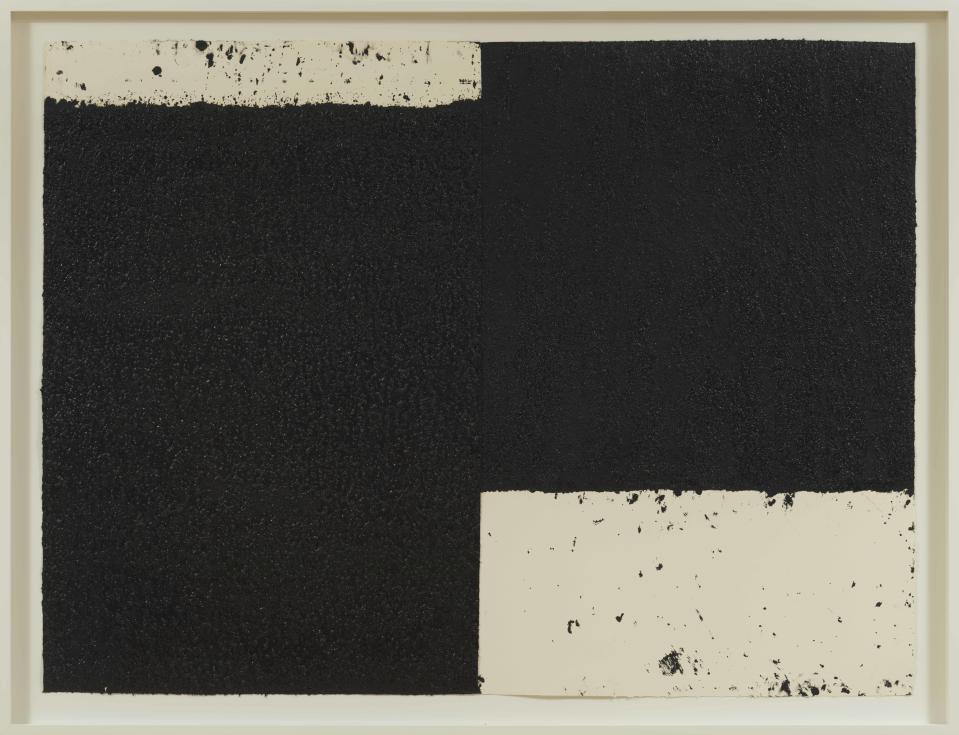

In the exhibition uptown on Madison Avenue, the paper works on view look deceptively simple in photos, but in person, the squares of black on cream seem to rise and fall. At Forged Rounds, the huge abstract forms, as you walk among and around them, evoke 20th-century industrial manufacturing towns, and their blistered, gritty surfaces in spots suggest nothing so much as decaying harborside cargo ports. Serra’s biggest works have always been ferocious and meditative, elegant and, in a moment, threatening, and Reverse Curve is all that: suggesting, in spots, a wall of protection or exclusion; a building collapsing; or a bolt of rust-colored cloth suspended and swirling. It is, for something hard and mean and powerful, gorgeous.

The gallery declines to disclose prices, but Serra sculptures have sold for up to $4 million at public auction. The drawings, made here with paint stick that leaves a thick, memorable, almost metal-like surface, have cracked the seven-figure mark. Two-dimensional works can be a hard sell for sculptors, as for some, they are ancillary to their practice. But Serra makes his own completely by hand, without assistants, and “they are not trinkets” to the bigger works, notes Vander Weg.

The works in the shows were not presold, she adds, and are not specific commissions for individual institutions or collections. And while certainly every Gagosian client owns or has been offered a Serra—this is his 31st show at the gallery—“there are always new collectors,” she says, laughing.

Triptychs and Diptychs runs September 16 through November 2, 2019, at 980 Madison Avenue (Drawings) Forged Rounds runs September 17 through December 7, 2019, at 555 West 24th Street (Sculpture) Reverse Curve runs September 17 through February 1, 2020, at 522 West 21st Street (Sculpture)

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest