Richland County has more monuments to Black women than anywhere else, researcher says

When you think about public monuments in the American South, you probably think of the Civil War, controversy around statues, and almost certainly of white men.

But Richland County has a different history that, while not hidden, is not as well known as the monuments you might be thinking of.

According to one researcher, the Midlands county has the most public memorials to Black women of any county in the United States.

Richland County has 17 monuments to Black women — nine historical markers, three historic sites and at least five street names.

That was something of a surprise to Alexandria Russell, a postdoctoral fellow at Rutgers University.

Russell grew up in Columbia and ultimately earned a doctorate in history from the University of South Carolina in 2018. But as a young girl, she didn’t think of the city as having that much public history to offer. Charleston was the state’s historical city, she thought, and she attended the College of Charleston for her undergraduate studies.

But when she started researching public monuments across the country for her dissertation, “Sites Seen & Unseen: Mapping African American Women’s Public Memorialization,” she realized that history, and especially history honoring Black women, was all around her.

“It was a discovery for me to find the town I came from, my hometown, has all these wonderful things,” Russell said. “I was excited to find that it’s so rich in memorials, and especially for Black women.”

For decades now, there’s been a push for more recognition of African-American history across the country, but in all her studies in multiple states, Russell not only said she’s never seen a locality with as many monuments to Black women, but some of Richland County’s sites appear to be unique.

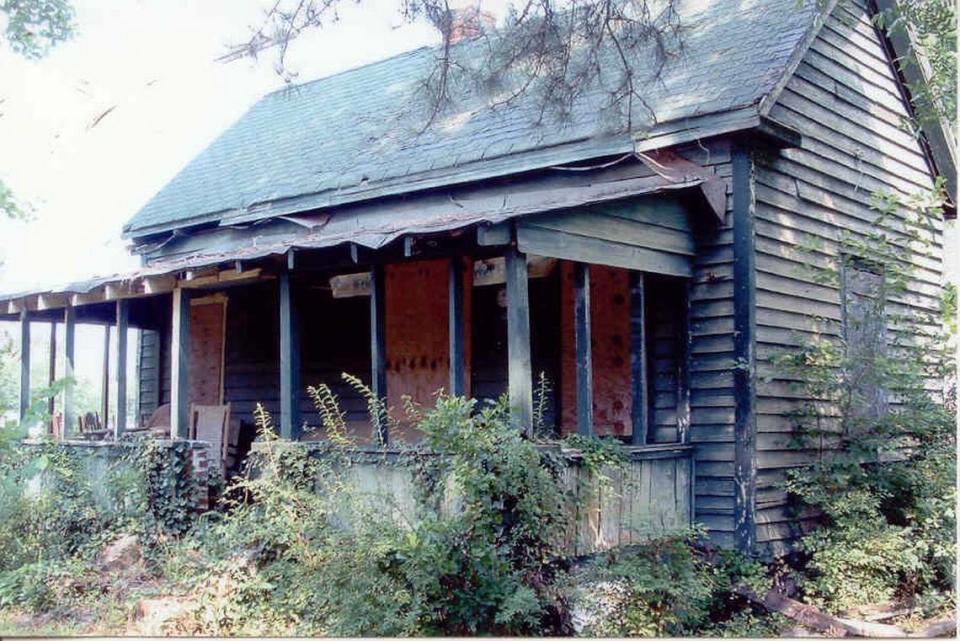

She points to the Harriet Barber House in Lower Richland, built on a 42-acre plot Harriet and her husband Samuel purchased in 1872 through the S.C. Land Commission. The commission was set up after the Civil War to allow freed slaves like the Barbers to purchase land. Portions of the land off Lower Richland Boulevard in the Hopkins community remain in the Barber family to this day.

“When you think about Black women in agriculture, the setting is usually a plantation, not Black-owned land that the family ensured survived for over a century,” Russell said. “That’s a historical narrative I had not come across.”

Closer to downtown, you can see the Mann-Simons Cottage at the corner of Marion and Richland streets. Celia Mann was born into slavery in Charleston, but earned her freedom and settled with her husband Ben Delane in this pre-1850 house. Working as a midwife, Mann would have been one of the few free African Americans in the city at the time.

From that position, the family were leaders in the Black community. Three Columbia churches — First Calvary Baptist, Second Calvary Baptist and Zion Baptist — trace their origins to prayer meetings held in the cottage.

“It’s significant to have a free family of color in the antebellum era owning their own house,” said Katharine Allen, research director for Historic Columbia. “It was nearly lost to urban renewal, but the Black community rallied to save it in 1970, and it became Columbia’s first Black museum.”

That time period produced the first spurt of African American monuments in the country, as the civil rights and Black Power movements produced the first African American studies courses in universities and a renewed interest in Black history.

But the movement for more public recognition has continued in the following decades. Only a couple blocks away from the Mann-Simons Cottage on Marion Street is the Modjeska Monteith Simkins House, home of one of South Carolina’s leading civil rights pioneers for 60 years.

A Columbia native, Simkins graduated from Benedict College in 1921 and became a teacher at Booker T. Washington High School in Columbia, until she was forced to leave the profession when she got married in 1929.

Instead, Simkins became a public health advocate. In 1931, and she became the director of “Negro Work” for the S.C. Tuberculosis Association, becoming the first African American in a full-time, statewide public health role.

Active in the Columbia chapter of the NAACP, she helped found the state conference of the civil rights organization in 1939 and served as its secretary for 16 years. She helped bring the Briggs v. Elliott case in the 1950s that challenged school segregation in South Carolina, paving the way for the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

When Simkins died in 1992, her small home was turned into a civil rights museum run by Historic Columbia.

Russell doesn’t believe Columbia intended to compile so many monuments to Black women, but because so many women played an important role in the community, they were remembered for their contributions when the opportunities arose to memorialize them.

“In Columbia, it’s just that the homes that were threatened with demolition, or the public history that gets attention, centered on Black women.”

Besides historic sites, the city has also worked to honor Black women with street names. Last year, it was announced a street in the BullStreet development would bear the name of Matilda Evans, an Aiken native who left South Carolina to earn a medical degree and became the first woman in the state to practice medicine in 1897.

Evans joins Celia Saxon, who was born into slavery but graduated from South Carolina College in 1877 and spent the next 50 years educating and caring for Black children in the capital city. Celia Saxon Street runs by the Drew Wellness Center off Harden Street.

In addition, the section of Washington Street between Assembly and Main is called Sarah Mae Flemming Way in honor of a young woman who protested segregated seating in 1954 by refusing to give up her seat on a Columbia bus, more than a year before Rosa Parks’ more famous protest in Montgomery, Alabama.

Other streets in the capital city named for Black women include Dawn Staley Way, a section of Lincoln Street near Colonial Life Arena named for the national championship-winning Gamecock women’s basketball coach, and Emily England Clyburn Way in the Greenview neighborhood, named for the civil rights activist, education advocate and late wife of U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn.

The latter provides another reason Allen with Historic Columbia sees for the area’s preponderance of honors for Black women; its leadership is eager to recognize their contribution.

“The elected representatives at every level here, from the city to the federal level, are really in tune with this history,” Allen said. “If some people don’t know Celia Saxon, the elected leadership here grew up knowing who she was.”

More markers honoring Black women could still be on the way. Just this year, the city saw its first statue of an African-American woman erected when the University of South Carolina put up a statue of Gamecock and WNBA basketball star A’ja Wilson outside the Colonial Life Arena.

Allen says historical markers are fairly easy to get placed in South Carolina.

“The great thing is that anyone can make a nomination to the State Archives,” she said. “You just submit an application showing where you think it is and why it’s historically important.”

Historic Columbia and the Richland County Conservation Commission are working on an additional marker to honor the Rollin sisters — Charlotte, Florence, Katherine, Marie Louise and Frances Ann “Frank” Rollin. The mixed-race sisters were active during the Reconstruction era in calling for women to be granted the right to vote. They organized a women’s rights convention in 1870, and chartered the S.C. chapter of the American Woman Suffrage Association.

For years, the “Rollin salon” at Senate and Sumter streets hosted interracial gatherings for a variety of social causes across Sumter Street from the S.C. State House.

When that marker is unveiled later this year, or even before, Russell asks that her fellow Columbians take in the area’s rich history for themselves.

“The main thing I want people to know is that it’s all right there,” Russell said. “I wasn’t aware of the vibrancy there. I hope people will hop in their car and go out and see it.”

Richland County historical markers honoring Black women

▪ The Alston House, 1811 Gervais St., where Caroline Alston both lived and ran a dry goods business in the 1870s and ‘80s, one of the few Black-owned businesses in the city.

▪ Celia Dial Saxon School, which opened as the Blossom Street School between Assembly and Park streets in 1898. It became an all-Black segregated school in 1929 and was renamed in honor of Celia Saxon, who pioneered African-American education in the capital city for more than 50 years.

▪ Columbia Hospital’s “Negro Nurses,” at Harden and Washington streets, marks the site of Columbia Hospital’s former Negro unit, and a nursing school and dormitory that produced more than 400 Black nurses from the 1940s to the 1960s.

▪ The Harriet Barber House, on Lower Richland Boulevard near Barberville Loop Road. Built on a 42-acre plot Harriet and her husband Samuel purchased in 1872 through the S.C. Land Commission, set up after the Civil War to allow freed slaves like the Barbers to purchase land. Portions of the land remain in the Barber family to this day.

▪ The Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home, 1713 Wayne St., run by Hattie Cornwell after the death of her husband, along with her daughters Geneva Scott and Harriet Cornwell, this home provided a safe stop for Black travelers before the hospitality industry was desegregated by the Civil Rights Act.

▪ Mann-Simons Cottage, 1403 Richland St., built before 1850, this was the home of the free Black couple Celia Mann and Ben Delane before the Civil War, one of the few households of free people of color in the city. The house was inherited by Mann’s daughter, Agnes Jackson Simons, and the family’s descendants maintained the home until it was converted into a museum in the 1970s.

▪ Matilda A. Evans House, 2027 Taylor St. From 1928 until her death in 1935, this was the home of Evans, an Aiken native who became the first Black woman to practice medicine in the state when she opened a practice in 1897. Evans went on to found Columbia’s first hospital for black patients and to advocate for public health improvements.

▪ Modjeska Simkins House, 2025 Marion St. For 60 years, this was the home of Modjeska Simkins, a Columbia native and Benedict College graduate who helped found the S.C. Conference of the NAACP and bring the Briggs v. Elliott case that overturned school segregation. The home became a public museum after Simkins died in 1992.

▪ Monteith School, 6510 Main St. Rachel Monteith reopened this former white school in 1921 as a school for Black students. She went on to serve as principal, and the school was named after her in 1932. Monteith’s daughter was civil rights activist Modjeska Simkins.

Street names:

▪ Celia Saxon Street, named for the pioneer in African-American education. Runs between Read Street and Walker Solomon Way near the Drew Wellness Center, one block east of Harden Street.

▪ Dawn Staley Way, named for the USC basketball coach who led the Gamecock women’s team to a national championship in 2017. A section of Lincoln Street that passes Colonial Life Arena.

▪ Emily England Clyburn Way, a section of Juniper Street near David Street in the Greenview neighborhood, former home of civil rights activist, education advocate and late wife of U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn.

▪ Matilda Evans Street, the former Williams Drive near Segra Park in the BullStreet neighborhood, named for the public health advocate and first woman to practice medicine in South Carolina.

▪ Sarah Mae Flemming Way, Washington Street between Assembly and Main, named for a young woman who protested segregated seating in 1954 by refusing to give up her seat on a Columbia bus, more than a year before Rosa Parks’ more famous protest in Montgomery, Alabama.