Could James White Parkway – and the racial divide it deepened – be undone? | Know Your Knox

What would it take to remove the James White Parkway to restore the connection between East Knoxville and downtown? It’s a question many residents have asked over the years.

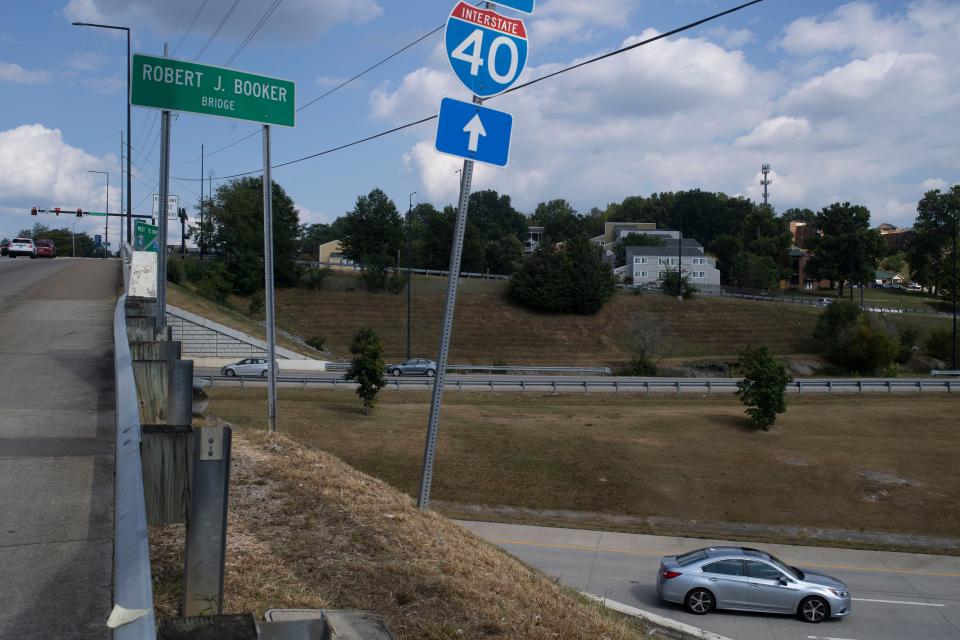

The road to nowhere, as many deem it, is a short stretch of highway that carves a prominent division between East Knoxville and the city's core.

For many residents, it's simply an Interstate 40 exit ramp or maybe just an inconvenient barrier to cross near downtown. But for others, it's the physical manifestation of a process that displaced African Americans from the heart of the city and decimated what was once a flourishing Black neighborhood.

One solution stands out: Take it out.

So how feasible is that? Some local experts say it's not possible and the James White Parkway is here to stay.

But the same was said about similar highways that divided other American cities, and public will drove Milwaukee, Portland and San Francisco to rip out and reroute highways to create a new vision for urban transit.

Mark Nagi, the Tennessee Department of Transportation's East Tennessee division spokesman, told Knox News that in his 12 years of working for TDOT, he has never been asked the question, even as daily traffic on the highway has declined more than 58% since its peak in 1990.

“I don't recall anything like that ever being done in East Tennessee,” Nagi said.

Rogero administration halted James White Parkway extension

Since the James White Parkway's construction in 1978, drivers heading south on the route have had two choices: Either take the exit to Island Home Avenue or to Sevierville Pike. A third exit option was discussed by the city in 2017 but was never built.

"It was intended to be a major corridor going toward the Great Smoky Mountains National Park going south. So now we have this major highway-looking thing that goes about a mile and a half and just dead ends,” Knoxville Parks and Recreation Director Joe Walsh told Knox News in 2017.

In 2013, the state proposed a $104 million James White Parkway extension that was stopped under the administration of Knoxville Mayor Madeline Rogero, which banded together with residents to stop the extension of the highway.

Rogero initiated the proposal to exclude the parkway extension from the Transportation Improvement Program. She advocated for enhancing current roads and preserving Knoxville's Urban Wilderness. The Knoxville Regional Transportation Planning Organization Board unanimously voted in favor of removing the project.

Highway at the forefront of urban removal legacy

Between 1959 and 1974, the city of Knoxville embarked on projects aimed at transforming its urban landscape. That included razing homes and commercial buildings on the eastern edge of downtown, as well as construction of the James White Parkway's interstate loop.

The Riverfront-Willow Street, Mountainview and Morningside projects included construction of the Civic Coliseum and changes to Interstate 40 and the James White Parkway.

This work demolished Black residences and businesses, effectively severing Black communities from the city's civic and business hub. This transformation physically isolated Black families, disconnecting them from economic opportunity, and those divisions persist today.

Banishing highways is not a new phenomenon

Throughout the nation, there is a concerted effort to eliminate highways that act as barriers within communities. In a bid to rectify the socioeconomic consequences of planning choices made many years ago, the federal government is allocating $1 billion over a span of five years to dismantle highways that create divisions in communities. The funding is a component of President Joe Biden's Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, which was established as part of the bipartisan infrastructure law passed in 2021.

Last year, Knoxville's African American Restoration Task Force backed an application from Knoxville's Community Development Corporation to expand trails and improve walking paths that would stretch from Knoxville's Botanical Gardens through the new Austin Homes development to the Tennessee Smokies stadium site adjacent to the Old City.

The application also included the widening of the narrow sidewalk along Summit Hill Drive where it crosses the James White Parkway.

That grant was not approved, but plans are underway to reapply for the next grant cycle, according to a KCDC representative at last month's task force meeting.

In the new application, plans for 10 pocket parks along the Beck Cultural Corridor project will be included.

Once finished, the Beck Cultural Corridor will feature numerous markers that allow access to information and images of places that might no longer exist but hold significance in the rich history and culture of the Black community.

What would it take?

Jeff Welch, executive director of Knoxville-Knox County Planning, told Knox News the first step to eliminating a highway such as James White Parkway would be TDOT giving up its ownership.

Next, someone would have to create a plan for all the traffic heading into South Knoxville, the interstate and the University of Tennessee.

Average daily traffic volume on James White Parkway has experienced a steady decline in recent years, particularly since 2014, according to TDOT traffic data. For 2023, the average daily traffic count stands at 26,487, representing the lowest figure ever recorded in the history of the highway. In 2021, it was slightly higher at 26,782. By contrast, in 1990, the highway reached its peak daily traffic volume with 63,600 travelers.

“They would essentially have to agree that we're not going to claim it as a state highway anymore and turn it over to the local government, and the local government would have to accept responsibility for the roadway and decide what they want to do with it,” Welch said.

"You have a lot of traffic on surface streets that are obviously heavily congested. Downtown streets can’t handle that type of additional traffic. I think the better idea instead of the unlikeliness of getting rid of James White Parkway would be to build over it,” he said.

What would building over James White Parkway look like?

"Freeway caps," often referred to as "lids," have emerged as an approach for addressing highways that have separated urban communities and rectifying poor infrastructure decisions made in decades past. Cities seeking to revitalize their downtown areas or uplift struggling neighborhoods are now developing "highway cap parks" by constructing decks over the existing freeways.

Within urban centers, highway deck parks offer a means to generate additional land and establish green areas that can stimulate the growth of downtown areas. They can help reunite neighborhoods that were divided by highways, especially those built in the 1960s and '70s.

Building parks on top of highways has become an increasingly popular solution. Dallas, Denver and Pittsburgh have deck parks, and many other U.S. cities have plans underway. Within densely populated areas, highway deck parks offer a means to generate additional land area and furnish green spaces, serving as catalysts for downtown development.

Welch said he thinks building over the James White Parkway could be a more viable game plan for the city.

"You could open up a creek, with green space over near the First Creek development, that becomes a linear park if the road wasn't there. Something like that would seem easiest without knowing what kinds of utilities are through there," Welch said.

For now, without a visionary to reimagine and make a move to get rid of James White Parkway, the legacy of urban removal remains.

Know Your Knox answers your burning questions about life in Knoxville. Want your question answered? Email knowyourknox@knoxnews.com.

Angela Dennis is the Knox News race, justice and equity reporter. Email angela.dennis@knoxnews.com. Twitter @AngeladWrites. Instagram @angeladenniswrites. Facebook at Angela Dennis Journalist.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: What would it take to get rid of the James White Parkway?