'We have to get rid of it,' Springfield mom says after kids find invasive hammerhead worm

When Jennifer Serfass heard her children yell, “Mom, look at this worm,” she expected an ordinary nightcrawler.

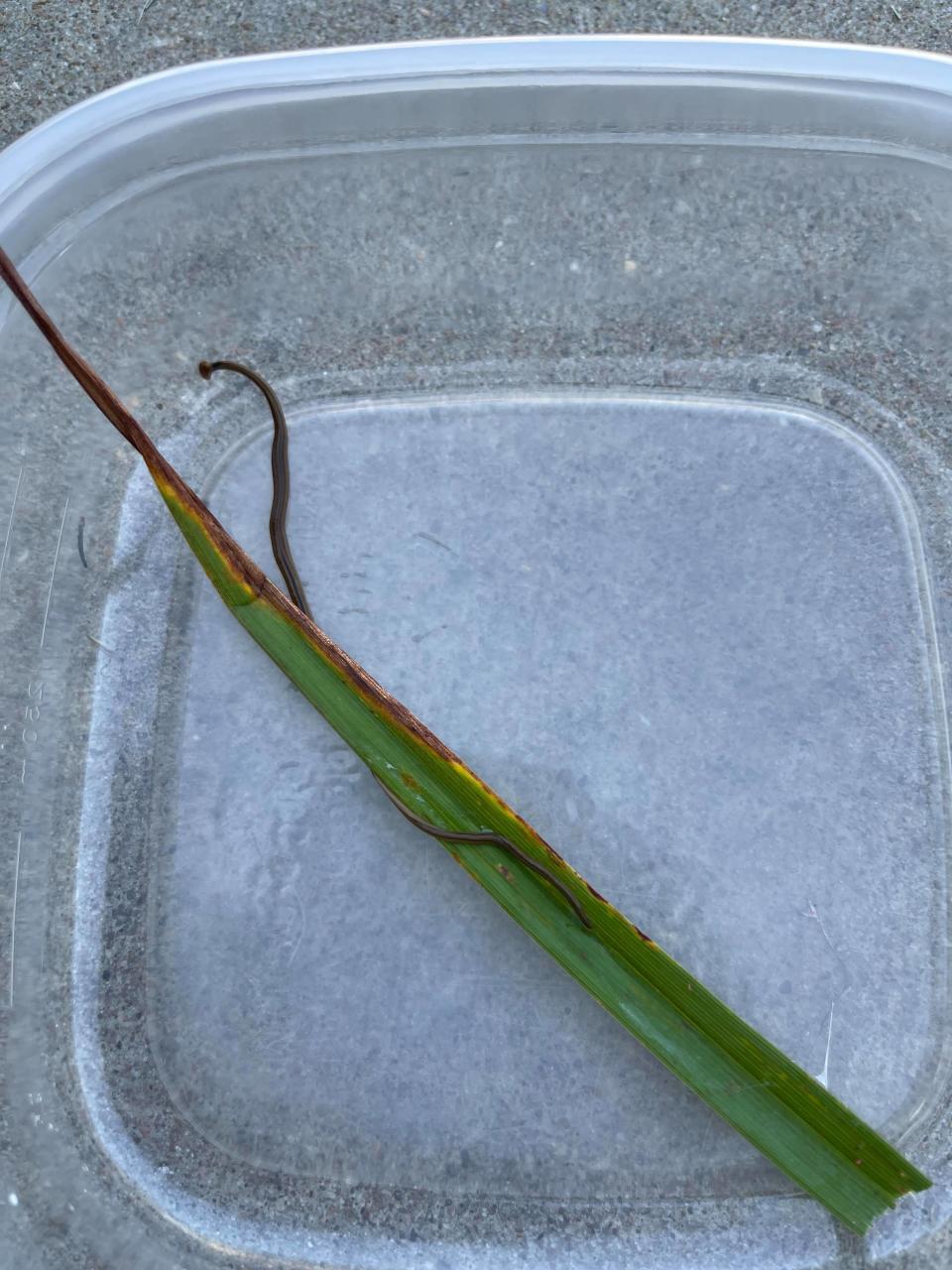

Rather than the squiggly body of a common earthworm, this one had a bulbous mushroom head.

“It was really long,” Serfass recalled in a phone interview with the News-Leader. “It moved slowly, like a slug.”

When she got a good look at it outside her home in southeast Springfield on June 7, Serfass thought the worm had something protruding from its mouth, which would have explained the hammerhead appearance. After some research, she discovered that look was all-natural.

What is a hammerhead worm?

The broadhead planarian was a hammerhead worm, or bipalium, and is considered invasive.

Serfass’ first reaction: “We have to get rid of it.”

If she chopped the pest into pieces, it would simply regrow its tail, Serfass learned online. The Springfield Conservation Nature Center also said she needed to dispose of it, but not by way of a knife.

“I had read other people say to use salt because they’re similar to slugs, so that’s what I did,” she said.

This learning experience was helpful not only to Serfass, but also her children, who range in ages from 6 months to 6 years old. She spared them the exact details of how the hammerhead worm met its end.

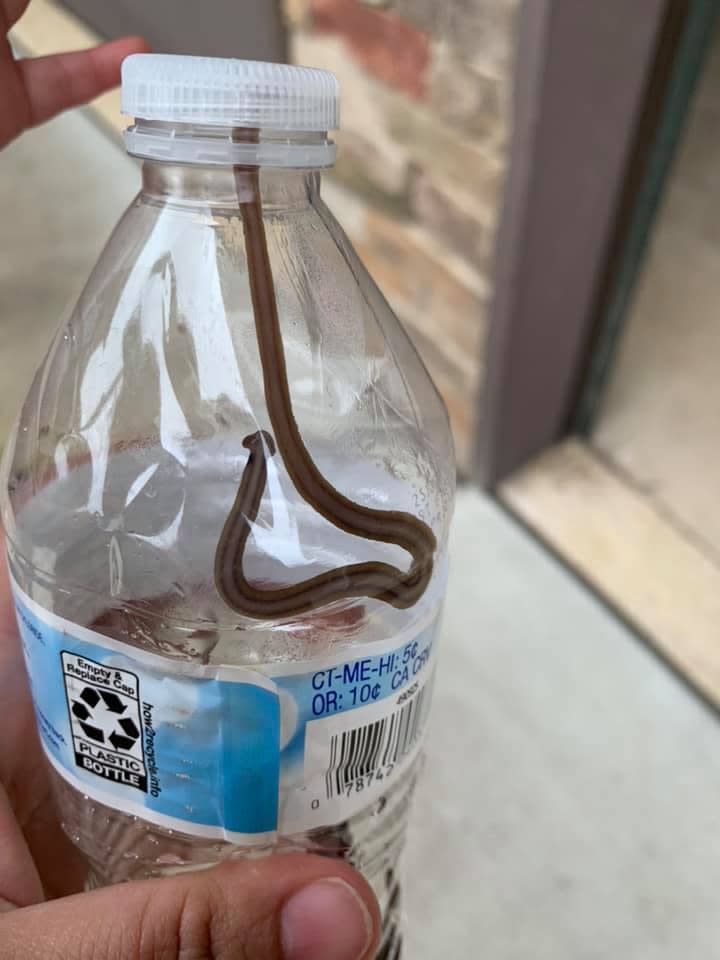

“I don’t think I told the truth to my children about what I did,” Serfass said. “My daughter came home from school and I saved it for her in a water bottle, and she said, ‘We should probably just let it go.’”

Serfass explained that, no, they couldn’t just let it go and why.

“I left it at that and then she didn’t ask again, so that was good,” she added.

Serfass shared the experience on social media in the Welcome to Springfield, MO Facebook group and the post exploded. With nearly 9,000 shares and more than 1,000 comments, people weighed in on the find while also expressing their astonishment.

“This is terrifying,” one wrote in the comments.

“Holy macaroni,” a person said, while another replied, “More like spaghetti.”

The visceral reactions are understandable, especially considering how predatory the hammerhead worms can be, said Kelly McGowan, a field specialist in horticulture with University of Missouri Extension.

Why are hammerhead worms bad and how do they get into the soil?

The invasive worms aren't toxic to humans or animals, but they prey on common earthworms and other soil-dwelling species, McGowan said.

“Earthworms and other little critters are very important for our soil health, and whenever you have a non-native species like the hammerhead worm that comes in and starts feeding on some of our native things, it can certainly affect our soil health,” McGowan said.

One of the first reports of a hammerhead worm in the region crossed McGowan’s desk in 2018. Since then, she began gathering data on sightings and determined the worms had made their way generally in southwest Missouri.

“Since they’re new to our area, we don’t know the extent of what that will mean,” McGowan said. “It could end up being nothing. There may be just a few of these things around, and it may end up being absolutely no big deal.”

There could be detrimental consequences, but it is still unknown, McGowan said.

When speaking with folks who spotted the invasive planarians, McGowan said many had recently brought in a load of soil or had purchased nursery plants.

“I’m suspecting these were accidentally introduced here in soil, in plants that have been potted up in other states and then shipped here, and those worms hitched a ride,” McGowan said.

Despite not being from the Ozarks, the hammerhead worms are adapting and acclimating.

“They’re surviving our winters, they’re reproducing, and their population is starting to grow,” McGowan said.

What happens if you cut a hammerhead worm in half?

Hammerhead worms leave a mucus trail and excrement that helps it glide along, McGowan said previously in a MU Extension article. The worms produce sexually by laying eggs and asexually by fragmenting and growing new heads and tails when cut into pieces.

If you find a planarian with a hammer-shaped head, McGowan supported Serfass’ actions: pour salt on it.

Nearly three months after finding the planarian, Serfass messaged the News-Leader to report she found another hammerhead worm about 10 feet away from where the original one was spotted.

Sara Karnes is an Outdoors Reporter with the Springfield News-Leader. Follow along with her adventures on Twitter and Instagram @Sara_Karnes. Got a story to tell? Email her at skarnes@springfi.gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: If you find a hammerhead worm, you should kill it with salt