Righting the past: Abraham, veteran of Negro Fort and Seminole Wars, is dead

Editor’s note: This is the 25th in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

Abraham, a veteran of the Battle of Negro Fort and respected elder of the Seminole people, died in what is today Seminole County, Oklahoma. The exact cause of death is unknown, but he was at least 79 years old.

A thin man whose voice was “soft and low, but very distinct, with a most genteel emphasis,” Abraham fought his way out of slavery to become a feared soldier, an inspiring leader and trusted interpreter whose words “flowed like oil.” After escaping slavery in Pensacola, he spent decades confronting American troops alongside Seminole allies.

Abraham was born in Georgia between 1787 and 1791 to parents of African descent. He later lived in Pensacola where Dr. Eugenio Antonio Sierra enslaved him. As a multilingual shipwright and carpenter later enslaved by the John Forbes & Company, Abraham was among the “most skilled and highly valued commodities in West Florida,” according to a noted historian.

Abraham lived in Spanish Pensacola until hostilities broke out between the United States and Great Britain in 1812. He may have heard about an 1814 British proclamation offering freedom and resettlement to enslaved people in the United States, and he was among the hundreds recruited in Pensacola by British Royal Marine Col. Edward Nicolls, whose abolitionist fervor and radical egalitarianism brought Spanish rebuke.

Righting the past: Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

Invited to Pensacola to defend their Spanish allies from American invasion, the recruitment of the region’s enslaved led to the British expulsion and precipitated an American invasion. U.S. Gen. Andrew Jackson—an enslaver who recruited enslaved people for his army in New Orleans with the promise of freedom, only to return these recruits back to slavery—used Col. Nicolls’ recruitment of enslaved Africans into the Royal Colonial Marines as his rationale to invade Pensacola in November 1814.

Outnumbered four to one, Nicolls’ multiracial fighting force—which included Abraham—left Pensacola for a British outpost on the Apalachicola River where the Royal Colonial Marines, along with Choctaw and Seminole allies, built a massive fortification later referred to as “Negro Fort.”

The war ended a few months later, but the well armed and trained militia remained at Negro Fort after the British troops were forced to evacuate. Spanish delegates, including Dr. Sierra, traveled to the fort to urge those now living in freedom to return to Pensacola and enslavement. Unsurprisingly, Abraham, like the vast majority of his compatriots, decided to remain at Negro Fort.

Isolated and independent, they would be joined by many more freedom seekers in subsequent months. The population swelled to nearly 1,000 residents, drawing the ire of enslavers across the southeast. Those who stayed in Negro Fort prepared for an imminent attack. In July 1816, the U.S. Army mounted its long-expected invasion of Florida, with the Spanish governor’s blessing, to destroy the free Black community. Early in the battle for Negro Fort, a single “hot shot” cannonball detonated the ammunition depot, killing hundreds and ending all resistance in the fort.

While the surviving Black and Native American leaders were executed, Abraham was among the few survivors who escaped capture and execution or re-enslavement by the American force that included Creek allies. He joined the Seminoles and continued waging war for freedom against the Americans for decades.

Abraham’s status among the Seminoles was complicated. According to one historian, he earned “a distinguished reputation among both the Seminole and their adversaries as a warrior, interpreter, and diplomat.” Although enslaved by the Seminole leader Micanopy for a period, he also became a trusted interpreter and military commander. Slavery operated very differently for Seminoles, closer to vassalage than chattel slavery.

In the early 1820s, Abraham was “rewarded” with a marriage to Hagar, “the widow of the former chief.” The two would have several children together, including Renty, Washington and a daughter. Decades later, Abraham purchased the freedom of his 16-year-old son, Washington, from Micanopy for $300.

Around 1825-1826, Abraham traveled to Washington, D.C. as interpreter for a delegation of Seminoles headed by Micanopy, who liberated Abraham for his service when they returned to Florida. He played a pivotal role in interpreting negotiations for the 1832 Treaty of Payne’s Landing. Abraham made his mark on the subsequent Treaty of Fort Gibson, witnessing the documents that led to the Second Seminole War.

Abraham was a key Seminole leader during this conflict. American commanders described him as “the principal negro chief” among the Seminoles and “a good soldier and an intrepid leader.” Often called “the Prophet,” Abraham commanded an army of about 500 freedmen and played a pivotal role in the negotiations that ended hostilities in 1838. This led to the surrender of the Seminoles and their transportation with “their negroes” to “Indian Country” in modern-day Oklahoma. “Abraham,” concluded one Army officer, “is obviously a great man.” He would later be accused of assisting the Americans to the detriment of the Seminoles, yet nothing substantial came from these accusations.

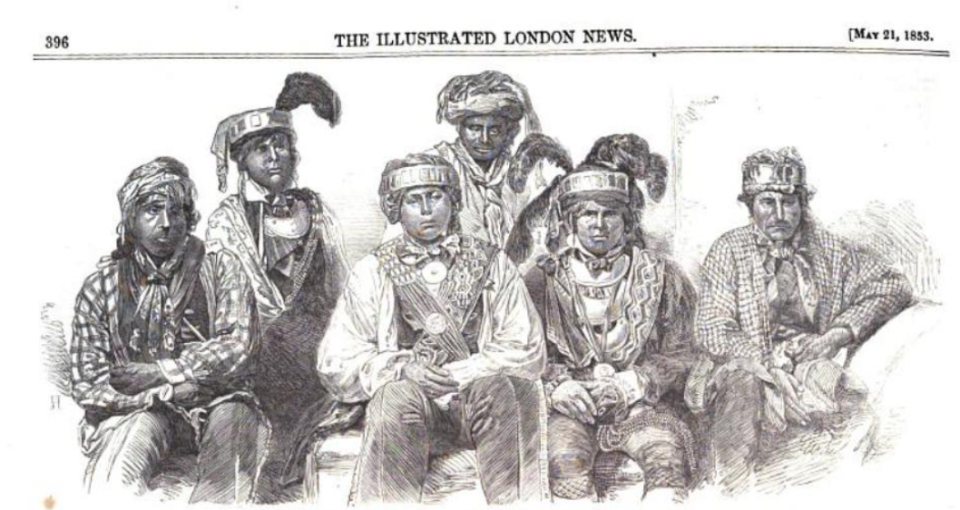

He remained a trusted Seminole leader in Oklahoma, serving as an interpreter between American officials and the Seminole into the 1840s. In 1852, he served once again as the translator for a party of seven Seminole leaders who traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with President Millard Fillmore to discuss the future of Florida’s remaining indigenous people. They visited Philadelphia and New York City where they had their portrait taken. The daguerreotype depicting the aged Abraham in an oversized turban is the only known photograph of a Pensacola freedom seeker. A sketch based on the image and a description of the Seminole delegates circulated widely in American and British newspapers.

Abraham would spend his final years farming in relative obscurity. The last surviving account of Abraham, published in 1870, reported “the old interpreter” was “still alive on Little River” in Seminole County, Oklahoma.

He died soon after and was reportedly buried in the Bruner Cemetery in nearby Bowlegs, Oklahoma. Born into slavery, Abraham spent his life fighting for the right of self-determination — first for himself, then for his family and adopted Seminole tribe.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Righting the past: Abraham, veteran of Negro Fort Seminole Wars, dies