Righting the past: John Brown, World War I veteran, laid to rest in Old Muscogee Cemetery

Editor’s note: This is the 10th in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

John Brown, a World War I veteran from Muscogee, Florida, died on Jan. 16, 1930. He was 33 years old.

Mr. Brown was born in Fort Deposit, in Lowndes County, Alabama, to George Brown and his wife Jane Seawright Brown in 1897. A few years later, Jane was a widow raising young John and his five siblings, including his older sister Rosa. By 1910, Rosa had married George Calloway. The couple worked as farm hands along with 13-year-old John, who boarded at the household of Lewis and Martha Dillard. Later that year, Brown’s mother married Enoch Goldsmith. Sometime in the next seven years, Mr. Brown and the Calloways moved to Muscogee, Florida, where John and George worked as laborers and millhands for the Southern States Lumber Company. They were part of a migration of African Americans to Escambia County, where jobs in the lumber and related industries were plentiful.

What is Righting the Past?: Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

On June 5, 1917, Brown registered for the draft as required by the Selective Service Act enacted the previous month. His registration card gives his race as “African” and describes him as tall with a medium build. Brown was one of 156 men — 111 of them African Americans — drafted from Escambia County in April 1918. They were willing to fight for a country that had often fought against them.

W. E. B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wrote a July 1918 editorial in the NAACP magazine, The Crisis, in which he urged Black Americans to support the war effort: “Let us not hesitate. Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy. We make no ordinary sacrifice but we make it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills.”

Private Brown served in the 810th Pioneer Infantry Regiment at Camp Green near Charlotte, NC. These military units performed essential duties and provided a logistical backbone for the US Army. When his unit was decommissioned in December 1918, Private Brown received an honorable discharge after eight months of service.

Righting the past: Walker W. Thomas, national newspaper correspondent and veteran, dead at 28

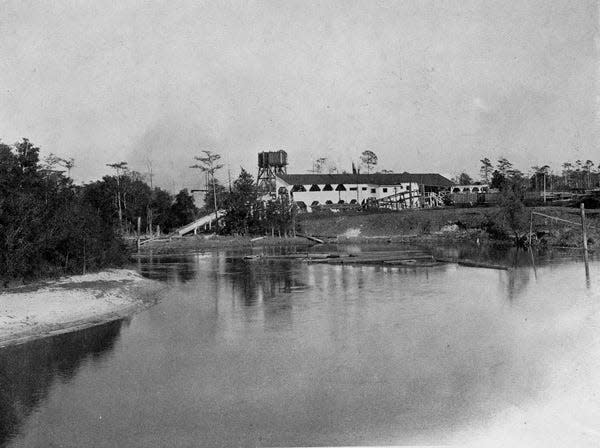

After the war, Mr. Brown returned to Muscogee to work as a millhand. He again lived with his sister, brother-in-law and mother, who was again widowed. The Muscogee Mill, which opened in 1873 by the Muscogee Lumber Company, had been operated by the Southern States Lumber Company since 1889. After decades of aggressive logging caused a shortage of pine in the local area, Southern States started to divest property and shut down the Muscogee Mill in 1925. In 1928, Southern States sold the entire town of Muscogee and surrounding land to B. C. Davis of DeFuniak Springs.

During this period of transition, John Brown married Francis Black in April 1929. The officiating judge made a racist quip about “Brown” marrying “Black” in The Pensacola Journal. The marriage would end in tragedy early the next year.

In early December 1929, a rabid dog bit Mr. Brown. He was admitted to the Pensacola Hospital on Jan. 14, 1930, displaying the neurological symptom of rabies called hydrophobia, a refusal to consume water or other liquids. He was strapped to a hospital bed while witnesses say he requested to be “put out of his misery.” He died two days later, with “hydrophobia” listed as the cause of death.

Escambia County saw an increase in rabies cases among dogs in 1930, and John’s death led to a campaign to inoculate dogs throughout the county. “It costs nothing and may prevent such an occurrence as that which has resulted in Mr. Brown’s case,” said Police Commissioner E. E. Harper. Sixty dogs received rabies vaccinations within five days of John’s passing. By April 1930, victims of dog bites immediately received a series of vaccinations before they showed advanced rabies symptoms.

Righting the past: War veteran and prominent citizen, John Sunday is dead at 86

Righting the past: Pensacola’s only Black mayor, Salvador Pons, is dead at 55

On April 23, 1930, Mrs. Brown gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Earnistine. Three months later, Mr. Brown’s sister, Rosa, applied for a veteran headstone to mark his final resting place in the African American section of the Old Muscogee Cemetery.

Muscogee struggled through the Great Depression and became a ghost town. Second-growth pine trees gradually returned to the area, harvested as pulp for the paper mill that opened in nearby Cantonment, Florida, in 1941. The cemetery continued to be used into the 1970s, although the pine forest reclaimed the Black section in the past 50 years. In 2016, local cyclist Bill Middlebrooks rediscovered this section of the cemetery and began a campaign to preserve the dozens of neglected graves — including Brown’s. International Paper, which now operates the Cantonment mill, supported these efforts. The Old Muscogee Cemetery was recently added to the Florida Master Site File with the assistance of the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN).

Muscogee Cemetery: A neglected cemetery, a ghost town, and one man's mission to help preserve Muscogees past

Righting the past: Veteran Henry Stalburt, champion of freedom, dead

Like the modest marble headstone that was for decades obscured by vegetation, Private John Brown’s story deserves to be uncovered. He represents both the working class whose labor supported Escambia County’s early economy and the military personnel who bravely responded to their nation’s call to service. Many abandoned African-American cemeteries in Florida have been identified, studied and protected thanks to new state and federal initiatives. These long overdue and ongoing preservation efforts are, in the words of University of West Florida archaeologist Margo Stringfield, “a starting point in expanding the national dialogue on our country’s history in a more inclusive fashion.”

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: WWI vet John Brown laid to rest in Muscogee Cemetery