Righting the past: John A. Gibson, education advocate and community leader, dead at 79

Editor’s note: This is the 19th in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

John A. Gibson, noted educator and community leader, died from heart failure in Pensacola on Oct. 3, 1906. A widower, Mr. Gibson was 79.

He was born in Nassau, Bahamas, on the island of New Providence on March 10, 1827. John appears to have grown up in the Anglican church and received an education that prepared him for a distinguished career as an educator.

Around 1850, he married fellow Bahamian Catherine Louisa Morey. She gave birth to their only child, William, on April 17, 1852. John, then 25, was working as a schoolmaster, potentially teaching for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

What is Righting the Past? Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

During the 1860s, John became a recognized community leader, being appointed lumber inspector for New Providence in 1864 and elected to a committee overseeing the establishment of a Voluntary Artillery Corps two years later.

The country’s hard economic times in the late 1860s likely pushed the Gibsons to leave the Bahamas. They ended up in Pensacola by 1872 where both would later become naturalized U.S. citizens.

With decades of teaching and administrative experience, John became a leader in Pensacola’s new post-war education system. Between 1880 and 1905, he taught and served as a principal at many Pensacola schools. He also worked as a deputy teacher examiner for the school district.

In the mid-1880s, John helped lead an effort to recruit and train African American teachers in Escambia County. Along with Charity Tucker and John T. Mark, he organized the Institute of Colored Teachers of Escambia County. Tucker was the wife of Thomas de Salle Tucker, the first president of the State Normal College for Colored Students, now known as Florida A&M University.

Heeding calls to raise the proficiency of all public school teachers, the institute offered professional development courses in content, pedagogy and classroom management. At a December 1887 meeting, one of the institute’s speakers spoke eloquently about the significance and importance of “the wonderful work of education.”

The institute also campaigned for national policies that strengthened education for African American students, sending a resolution to Congress in 1887 to support the Blair Education Bill. This bill, introduced by a Republican senator from New Hampshire, aimed to provide substantial federal support to public schools struggling to reduce high illiteracy rates. Both Black and white students, explained Senator Henry W. Blair, were “growing up in absolute ignorance of the English alphabet.” The bill was defeated four times, the last time in 1890. It would not be until 1965 that Congress enacted a law “to strengthen and improve educational quality and educational opportunities in the nation’s elementary and secondary schools.”

In 1879, 1882 and 1885, Pensacolians elected John A. Gibson a city alderman. He joined a distinguished group of at least 15 people of color who served on the board during Reconstruction, including businessmen John Sunday and Salvadore Pons, educator Reuben H. Matthews and stevedore Eli Johnson.

Righting the past: Pensacola’s only Black mayor, Salvador Pons, is dead at 55

Righting the past: War veteran and prominent citizen, John Sunday is dead at 86

John was also a leader in Pensacola’s vibrant masonic community, serving as chapter secretary and, later, high priest of the Mount Moriah Chapter No. 18 of the Royal Arch Masons. He would also serve as the District Deputy Grand High Priest, a state-wide leadership position that connected him to prominent African Americans across the United States.

John and Catherine Gibson remained devout Anglicans throughout their lives. They worshiped at St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church, where Mrs. Gibson was noted for her strong faith and Christian practice. John served as a lay leader, deacon and minister. In 1897, he officiated the wedding of his neighbors, James Jackson and Susie Kyer. In 1903, he worked with the Rt. Rev. Edwin G. Weed, the third Bishop of Florida, to establish an Episcopal mission in the West Hill neighborhood.

When Catherine died on March 24, 1902, the school board suspended classes at his school so teachers could participate in her funeral. Rev. Percival H. Whaley, rector of Christ Church, gave the obsequies at the Gibson home. John later penned a memorial to Catherine, describing her as “a devoted wife, a loving companion and a good Christian.”

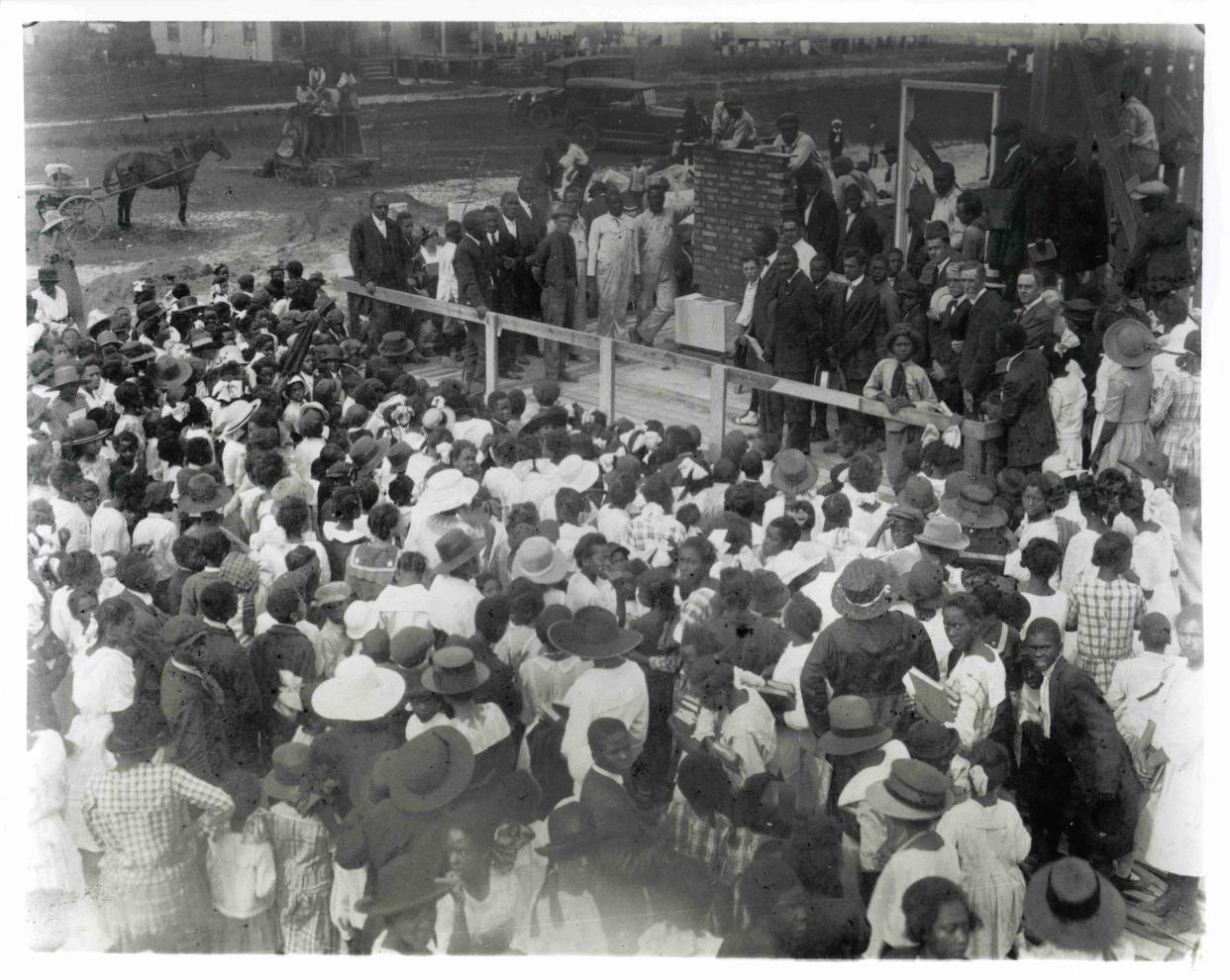

John A. Gibson died on Oct. 3, 1906, less than a week after a hurricane devastated Pensacola. As the city rebuilt, Gibson was laid to rest at St. John’s Cemetery. No public acknowledgment of his half-century of public service or advocacy came until the Escambia County School Board named its newest segregated intermediate school after Gibson in 1921. Located at 710 N. C St., the John A. Gibson School’s first principal was Charles E. McFarlin, another member of St. Cyprian’s.

For over 50 years, the John A. Gibson School served as a monument to a prominent African American educator. When it closed in 1974, the school became the headquarters of Escambia’s County Head Start Program, inaugurating a new chapter in providing strong educational opportunities to Pensacola’s children. In his faith, his commitment to exceptional teaching and his advocacy for his community, John A. Gibson represents the hope for education.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: John A. Gibson, education advocate and community leader, dead at 79