Righting the past: Walker W. Thomas, national newspaper correspondent and veteran, dead at 28

Editor’s note: This is the ninth in a series of historical obituaries written today to honor the men and women of the past who were denied the honor at the time of their death because of discrimination due to their race and/or gender.

Walker Wilmer Thomas, formerly of Pensacola, died on April 29, 1921, in New York City. He was 28. Throughout his short life, he strove to improve the lives and opportunities of African Americans while demonstrating the quintessential American virtues of hard work, entrepreneurship and patriotism.

Mr. Thomas and his twin brother Walter were born in Pensacola on July 25, 1892. Their parents, Mathew and Mary E. (Ames) Thomas, were born in Alabama during the Civil War. The twins had four other siblings: Joseph, Cora, Urial and Frances. To support his family, Mathew worked various jobs over the years, including as a family butler to William H. Knowles, a prominent Pensacola banker, and as a porter at the First National Bank.

Righting the past: Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

Henry Stalburt: Righting the past: Veteran Henry Stalburt, champion of freedom, dead

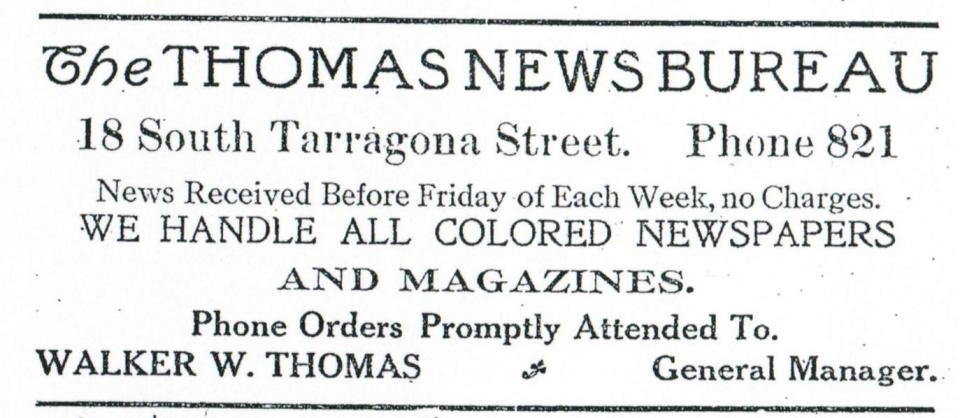

In 1910, 18-year-old Walker Thomas began serving as the special agent and local correspondent for the Indianapolis Freeman, a nationally prominent Black newspaper that he distributed in select Pensacola drugstores. The following year, he added The New York Age to his portfolio and opened the Thomas News Bureau.

Thomas wrote local society columns that were published in both newspapers. Like many society writers, Thomas’ reports often described his activities — re-enrolling in Pensacola’s only Black high school “after a three years’ vacation,” being elected president of the school’s literary club and attending his brother’s wedding. His articles offer invaluable insights into Pensacola’s Black community life during the 1910s, including detailed descriptions of social and religious gatherings, recreation and sports, to broader assessments of the community’s health and wellness.

In 1914, Thomas took on a partner, J. Caesar Lewis, and renamed the newspaper business to the Thomas & Lewis News Company. The same year, the local newspaper The Colored Citizen began publication, with Thomas contributing a society column titled “Seen and Heard While Passing.”

Thomas was an early adherent of what contemporary observers called the “grindset,” i.e. an unrelenting pursuit of numerous entrepreneurial endeavors. In 1910, he sold buttons supporting Black boxer Jack Johnson’s “Fight of the Century” against “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries. In 1912, he operated the El Centro Buffet and Ice Cream Parlor, boasting the “only colored place in the city that has music while you eat.” As proprietor of the Walker W. Thomas Decorating Company, he created elaborate decorations for special events, including wedding receptions and Carnival masquerades. In 1914, he and Warren E. Gregory opened the Palace Shoe Shining Parlor, which featured a public reading room. Thomas catered to Black and white customers, offering newspaper and shoe-shining delivery “anywhere in the city.”

Thomas also found time for community service. In 1913, as president of the Young Men’s Athletic Association, he helped establish a local Y.M.C.A. for African Americans and participated in fundraising activities to support it. He was active in the fraternal organization Knights of Pythias and the Young Men’s Progressive Association, serving as president of the latter in 1916. That summer, Thomas organized a memorial service for African-American soldiers who died in the Battle of Carrizal, pursuing Pancho Villa. On July 16, mourners marched from Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church to the Mount Olive Church (now Lily Hall).

Mary Higgins: Righting the Past: Pensacola teacher Mary Higgins died unexpectedly in fire at her home

Donald Reed Sr.: Donald Reed Sr., a leader in Pensacola business, life and community, died at age 86

In March 1917, as the United States inched towards involvement in World War I, Thomas spearheaded plans to begin local training of Black cadets. The U.S. declared war on Germany the following month, and Thomas was among the first 15 men drafted into the American Expeditionary Forces (A.E.F.) from Escambia County. On Sept. 5, he departed for France to serve in the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, including the 301st Labor Battalion and the 304th Service Battalion. Five months later he was promoted to corporal.

After 17 months of service, Thomas was discharged and headed to St. Louis, Missouri, to live near his family. He worked at the recently opened Pine Street Y.M.C.A., which quickly became a hub of Black social life and civil rights organizing. Thomas was a passionate advocate and community organizer. In July 1919, he wrote to The Crisis, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.), praising its founder and editor W.E.B. Du Bois: “I must say in behalf of all the soldiers Colored of the A.E.F. Hats off to Mr. DuBose [sic], the living M.O.S.E.S. … The Race should be proud of Mr. DuBose and the movement… every colored soldier of the A.E.F. should be a member of this organization.”

Perhaps inspired by Du Bois and the burgeoning Harlem Renaissance movement, Thomas moved to New York City by 1920. He lived in Harlem and worked as a letter carrier when he became ill and was admitted to the Sea View Hospital on Staten Island. After more than a month of treatment for chronic tuberculosis peritonitis, Thomas died on April 29, 1921. His mother arranged for his body to be returned to St. Louis, where he was buried in the Rural (now Bellefontaine) Cemetery on May 4, 1921.

John Sunday: Righting the past: War veteran and prominent citizen, John Sunday is dead at 86

Salvador Pons: Righting the past: Pensacola’s only Black mayor, Salvador Pons, is dead at 55

Walker Thomas’s life was a flame that burned brightly but briefly. He committed himself fully to every endeavor — to his business ventures, community and nation’s service. Through his love of writing and literature, he communicated the story of Black Pensacola to the rest of the country. Committed to social progress, he blazed a trail that led him to France, St. Louis and, finally, the bustling streets of Harlem. While his story ended there far too soon, Walker’s legacy of service is an inspiration to subsequent generations.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: Righting the past: Walker W. Thomas, newspaper correspondent, dead