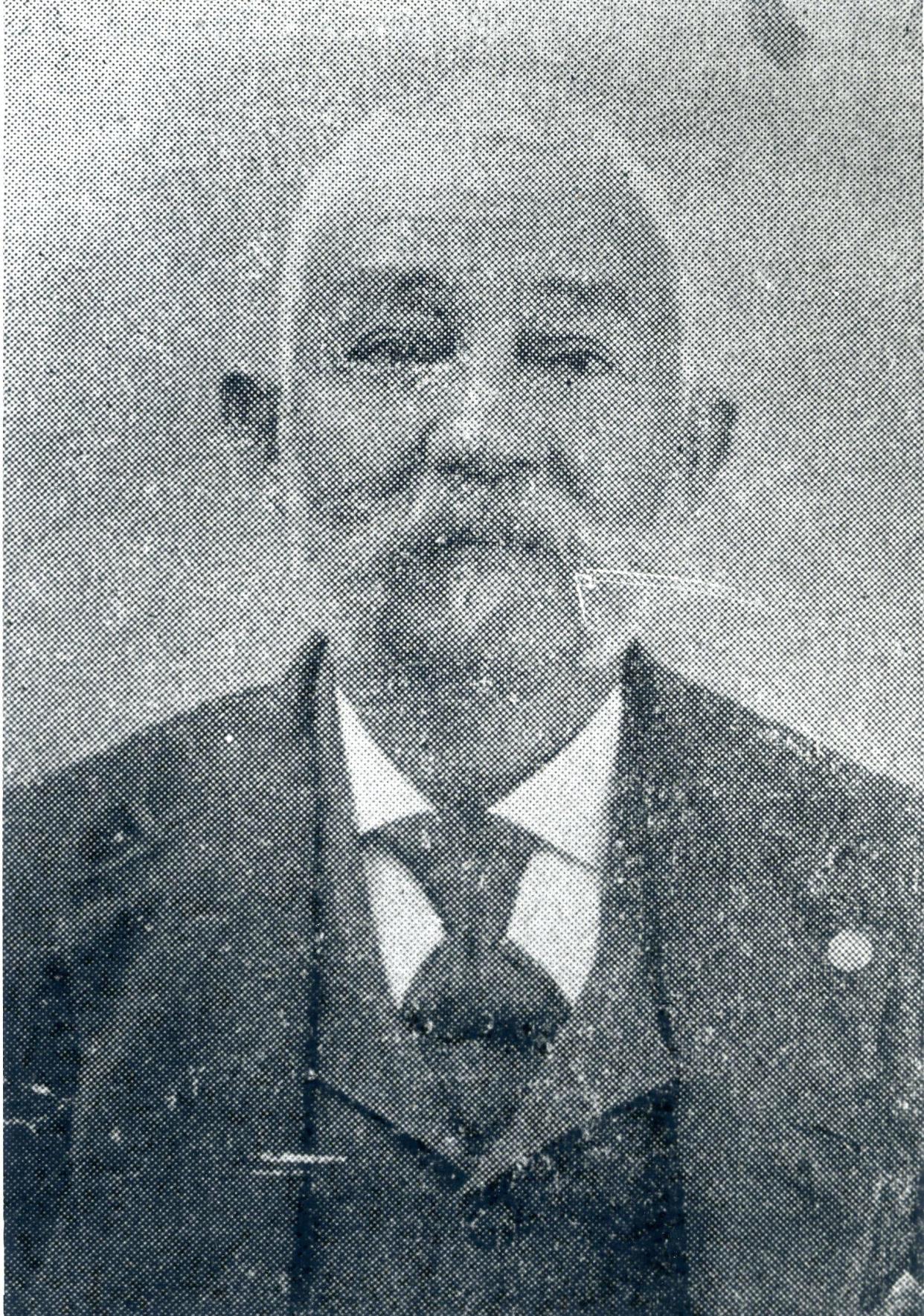

Righting the past: War veteran and prominent citizen, John Sunday is dead at 86

John Sunday, a prominent citizen of Pensacola who fought to end slavery and helped rebuild the city after the Civil War, died on Jan. 7, 1925. He was 86 years old.

Throughout his life, Sunday was active in Pensacola, whether it be in the construction trade or local politics. More than nearly any citizen of the city, Sunday represented not only the past but also the future of Pensacola.

Born in 1838 to an enslaved mother and a white farmer, John Sunday was named after his father and freed at the age of 2 upon his father’s death.

Why are we writing obituaries from past?Their history wasn't just forgotten, it was buried. Today we tell their stories.

Despite being a free man of color, Sunday was African American in the Deep South where life was precarious at best and dangerous at worst. Though Pensacola in the pre-war years offered more opportunities for free people of color than much of the Deep South, the Southern institution of chattel slavery was an ominous part of daily life and a constant reminder of his own enslavement.

When war broke out between North and the South, Florida seceded from the Union. After Pensacola’s brief time in the Confederacy ended, and Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the U.S. military soon allowed African Americans to join the fight.

One of the first from Pensacola to join in this fight to end slavery was John Sunday.

According to his military service record, John Sunday “[j]oined for duty and enrolled May 15, 1863” in Pensacola, Florida. Sunday joined the army as a private and was soon sent to join the 6th Regiment of the Corps d’Afrique in Port Hudson, Louisiana. He was 25.

The unit Sunday joined fought in the Siege of Port Hudson and was one of the first African American regiments to engage directly with the Confederate Army.

The Union Army reorganized Sunday’s regiment officially as the 78th Infantry of the United States Colored Troops. He remained with the 78th until the end of the war, rising to the rank of First Sergeant.

Dedication:John Sunday helped shape the course of Pensacola. A century later, he's getting his due

More:Pensacola City Hall park to be named John Sunday Plaza after prominent Black businessman

Discharged after the war, Sunday’s service record stated that he had “been furnished with transportation and subsistence in kind for the journey to New Orleans, Louisiana.”

Once Sunday came back from his military service, he returned to his home with a wife, whom he met in Louisiana.

With the end of slavery and federal troops occupying much of the South, there were unprecedented opportunities for African Americans throughout the region. Where they were once seen as property, the Black population now could vote, earn wages, serve in the military, and even hold political office.

Almost immediately upon his return, Sunday began working as a mechanic at the Pensacola Navy Yard and later as a customs inspector for the Port of Pensacola. During this time, Sunday began acquiring property and building homes throughout the city. Trained as a carpenter, Sunday used his skills to work to establish his wealth in real estate, a near impossible task before the war.

During the Reconstruction period, Sunday began his official service to Pensacola and the state of Florida. In 1874, John Sunday served as the second African American to represent Escambia County in the state legislature. After serving the State of Florida, Sunday served as a councilman for the city of Pensacola. He held that position until former Confederate Edward Perry was elected governor in 1885, bringing about an end to the multiracial government of Pensacola and ushering in what would become known as Jim Crow laws, a series of laws that legalized racial segregation.

After Sunday and his Black colleagues were forced from office, the Civil War veteran set his sights on his community, first by helping to found an African American chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Union veteran organization, where he served as post-commander. Then he focused on broader community work, including helping to found an orphanage in Pensacola and the Creole Catholic Benevolent Association.

Meanwhile, Sunday’s wealth grew as his construction business flourished and continued to build throughout the city, most notably in Pensacola’s segregated Belmont-Devilliers neighborhood. Mentioned by name in Booker T. Washington’s “The Negro in Business,” Sunday was described as the “wealthiest colored man” in the region. Washington wrote: “He owns valuable holdings in the principle business streets of the city, and employs steadily a force of men to repair old and build new houses.” Among those businesses were his construction company, several taverns, and a grocery store.

A devoted Catholic, Sunday donated some of his personal land, at the behest of his sister Mercedes, to build St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. The church was founded in 1891. A decade later, Sunday built his home nearby. He lived there until his death.

Born into slavery, Sunday was freed and fought against the Confederacy to end slavery. He returned to his hometown and rose to prominence in politics while prospering in business. He gave to his community and his former comrades. Few people have represented Pensacola, both literally and figuratively, as had Sunday.

John Sunday is survived by his wife, Seraphine Landry, and his children Samuel, John, Edward, and Henry. He is preceded in death by his mother Jinny, his father John, and his children Amiele, Charles, and Daisy. Sunday will be buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery.

This article originally appeared on Pensacola News Journal: John Sunday obituary: Righting the past means rewriting obituary