Riots helped elect Nixon in 1968. Can Trump benefit from fear and loathing too?

The grainy footage shows a young CBS News reporter immersed in a large milling crowd. Suddenly he is set upon by security guards who encircle then assault him, violently forcing him to the ground on live TV.

Related: Trump reaches for Nixon playbook after protests that have rocked America

The reporter emerges seconds later looking flustered. “I’m sorry to be out of breath,” he tells his viewers. “But somebody belted me in the stomach. The security people put me on the deck.”

That 30-second clip could have been taken any night over the past two weeks from one of the anti-racism protests that have erupted across 750 US cities. Journalists reporting on the George Floyd uprisings have been attacked by police using teargas, rubber bullets and batons almost 300 times.

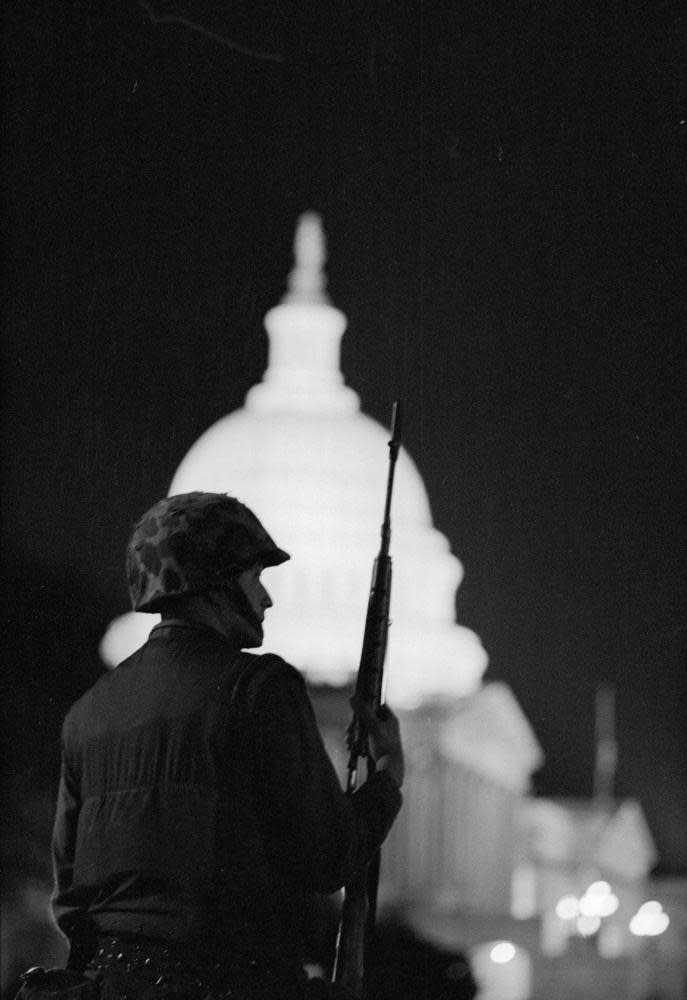

In truth, however, the video of the reporter being punched in the solar plexus was taken in August 1968. It was one of the memorable images of that chaotic and bloody year which is increasingly being held up as a parallel of our own volatile times in 2020.

The reporter was Dan Rather, a star TV correspondent who was to go on to become anchor of CBS Evening News. He was covering the 1968 Democratic national convention in Chicago, one of the low points of that year of strife, where violence erupted in police riots outside the convention hall echoed by the Rather attack on the conference floor.

“They almost knocked me out,” Rather recalled in an interview with the Guardian. “It was all captured on live television, and though in the grand scheme of things it was a minor incident, it became emblematic of the moment.”

Forty-two years after those events, Rather, 88, remains a media powerhouse. Today his voice is amplified not by the TV networks but through social media – he has almost 3 million followers on Facebook.

He continues to be one of the most acute observers of the political scene. Given his long reporting career at the coalface of American politics, he also has one of the sharpest takes on the parallels between 2020 and 1968.

“In 1968, the United States was in a state of shock,” he said. “The Vietnam war was going badly, there were racial uprisings and unrest, Dr Martin Luther King was assassinated and then Robert Kennedy, and all of this was coming together in the summer of 68 when it all looked to be going to hell in a hat.”

Like today, 1968 saw racial tensions boil over in more than 100 cities; like today, the country was riven by such partisan divisions it seemed to be ripping apart at the seams.

And like today, 1968 even had its own pandemic, the “Hong Kong flu” that claimed the lives of 100,000 Americans.

In the past few days another aspect of the parallels between 1968 and 2020 has exploded on to the nation’s consciousness: the warped character and dark scheming of their respective Republican leaders – Richard Nixon and Donald Trump.

There has long been an affinity between these two men. In 1987, Nixon wrote a letter to Trump in which he recounted that his wife, Pat, had seen the real estate developer on television and predicted “whenever you decide to run for office you will be a winner!”.

Then there’s the Roger Stone connection. The political dirty-trickster was an adviser to Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, having advised Nixon in an earlier era – he even has a Nixon tattoo on his back to prove it.

Nixon and Trump also share many of the same twisted traits. For both of them political power was something to be bent to their will for personal benefit.

They both had a way of brooding inside the White House, allowing their resentments over how they were perceived by the public to ferment.

This month Trump took the connection with his predecessor to a new level. On 1 June, standing in the White House Rose Garden, he declared himself to be a “law and order” president, vowing to deploy all federal resources – including the military – to staunch the “rioting and looting” he said was gripping America.

Trump then carried out the political act that rushed instantaneously into the history books. With the help of his attorney general, William Barr, he cleared a path through peaceful protesters using teargas and flash bangs, then walked accompanied by his top general in uniform to St John’s church for a photo op, Bible aloft.

“I see it as a direct copy,” Rather said. “Trump very clearly has decided to build his re-election campaign strategy around that of Richard Nixon and his 1968 campaign. The scene when he went to St John’s church, demonstrating ‘law and order’ as he went, says to me that he has looked at the Nixon victory in 68 and said, ‘This can be one of my paths to re-election.’”

Trump’s mimicry of Nixon is contained right there in the phrase “law and order” – rhetoric that had been familiar in the deep south for decades but which Nixon brought for the first time to the national political stage. In his acceptance speech for the Republican presidential nomination in Miami in August 1968, just a few weeks before Rather was decked in Chicago, Nixon addressed himself to the “forgotten Americans”, the “voice of the great majority – the non-shouters, the non-demonstrators”.

He might just have said: “Whites.”

Nixon spoke luridly about the state of the country, with its “cities enveloped in smoke and flame”. Unveiling the “law and order” catchphrase that was to define his presidential campaign, he vowed to open a new front against the “filth peddlers and the narcotics peddlers who are corrupting this country”.

Though Nixon denied it at the time, his law and order stance was suffused with racial undertones. He saw a political opening in the growing anxieties of many white American voters amid a rapidly changing landscape following the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 and the urban unrest of largely African Americans following the assassination of King.

Todd Boyd, chair for the study of race and popular culture at the University of Southern California, said Nixon used dog whistles to court the fears of disgruntled white America. “A lot of white voters were responding to the unrest not by seeing black people fighting for their rights, but as black people complaining.”

Nixon’s promise to crack down on the protests was calculated. “He recognised he couldn’t come out and say, ‘I want to dominate black people’, but he could say ‘law and order’. It was a very effective linguistic strategy that worked in 68 and for a long time after.”

Just how effective it was for Nixon is shown in an ingenious piece of academic research by Omar Wasow of Princeton University. Wasow wanted to measure the impact of the violent protests following King’s death on white voting patterns in the 1968 election, so he compared election results from largely white constituencies that had been in close proximity to scenes of rioting with similar white areas where there had been rainfall on the night of the unrest – a well-established dampener of protest passions.

He found a remarkable swing of up to 8% among white voters against Nixon’s Democratic rival, Hubert Humphrey, in those areas where there had been no rain that night. Wasow concluded that, writ large, Nixon’s exploitation of the protests through his “law and order” dog-whistling had essentially handed him the presidency.

Not only has Trump taken to wielding the “law and order” baton on Twitter with abandon, but he has gone where Nixon never dared to tread – spouting direct threats of violence and using openly racist language. When he was asked by Fox News on Thursday to explain his tweet glorifying violence by saying “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”, Trump said he thought – inaccurately – that it had come from the former police commissioner of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo (in fact it was a 1967 comment by the Miami police chief).

Rizzo was responsible for some of the most brutal policing in US history. His favored law and order response to peaceful demonstrations was to order his officers to mount motorbikes and run over the protesters.

Trump’s intentions in all this are clear – to try to repeat the Nixon playbook and turn white voters’ deep-rooted racial anxieties to his advantage in November. The billion-dollar question is: will it work?

Eduardo Porter is a social analyst who fears that it might. In his new book, American Poison, he argues that racial hostilities have so distorted the social contract in America it has turned the country into a failed state.

“It’s all about sharing the bounty of citizenship,” Porter told the Guardian. “White Americans have a real difficulty with doing that.”

He sees the current moment as a tribal inflection point that could trigger white fears, much as it did in 1968. In the late 60s the inflection point was the upheaval of civil rights legislation that was opening the doors for African Americans to the bounties of citizenship, provoking Nixon’s “law and order” backlash.

Today, the basic demographics of the country are shifting, with white people destined to lose their status as the majority of the population by 2045. “That demographic fear is an important driver of white political activity, and it’s what Trump is playing on when he talks about thugs and looting and the burning of buildings.”

Against that possibility, Americans under 40 have had much more experience of living in multicultural communities, and as a result there is a social ease that is powerfully illustrated by today’s nationwide protests in which blacks and whites march shoulder to shoulder in an unprecedented display of solidarity.

But Porter also reminds us that older, more conservative voters tend to turn out in presidential elections in higher numbers. “That residual, more racially hostile part of the electorate is particularly riled and fearful right now, and I wouldn’t find it crazy if they push Trump over into victory again.”

Timothy Naftali, a New York University historian who was founding director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in California, rates Trump’s chances at being re-elected less highly. Like Rather, he is convinced that Trump is copying the Nixon playbook.

“He is absolutely trying to revive the 68 metaphor. He is scrambling in a cynical and irresponsible way to ginny the system so that he can eke out a victory,” Naftali said.

But Naftali went on to argue that his literal repeat of Nixon’s “law and order” gambit might be Trump’s undoing, as it is based upon a fundamental misreading of history. Nixon in 1968 was the outsider, seeking to challenge a Democratic White House in the form of the lame-duck president, Lyndon Johnson.

Trump, by contrast, is an incumbent president trying spuriously to wrap himself in the cloak of the outsider. “It shows the absurdity of the man that Trump thinks he can run as an outsider when he is the ultimate insider. He got it wrong. He clearly misunderstands the moment. The 68 analogy is a trap he is creating for himself.”

Which brings us back to Dan Rather and his assessment of Trump’s Nixon ploy. The legendary reporter said he was appalled by the optics of the St John’s church photo op.

“This is the scene from some tinhorn dictatorship, using the church as a political prop with your in-uniform military generals backing you up as citizens are beaten and gassed,” Rather said.

“This election may well boil down to this,” he said. “Are the white voters in the suburbs more afraid of Trump than they are of the protesters?”

I ask Rather to answer his own question.

“I want to believe that the combination of the fear and disgust that a lot of people have with President Trump’s leadership will be a greater motivation than whatever racial fears they might have. I want to believe, and I do believe.”

Rather’s personal hope is that he’ll be around to see whether he is right. “I’ve been lucky and blessed to live this long,” he said. “Elections are the dance of democracy. I’d sure like to see this last dance through.”