Rip currents: What you need to know for safer swimming on Cape Cod

What's more dangerous than sharks? Rip currents, powerful and difficult to identify channelized currents of water rushing back to sea. They can pull swimmers offshore and turn a carefree swim into a grueling fight for survival.

"Almost every day at the beach there could be a rip current," said Gordon Miller, North District Lifeguard Supervisor at the Cape Cod National Seashore. "They didn't disappear when the sharks showed up."

According to the United States Lifesaving Association (USLA), rip currents "are the #1 hazard at a surf beach, leading to tens of thousands of rescues by lifeguards and over 100 drowning fatalities every year in the United States."

By contrast, there were 11 shark-related fatalities in the world in 2021, according to the University of Florida's Florida Museum of Natural History.

Rip currents can develop on any beach with breaking waves. On Cape Cod, these surf beaches include those that face the open Atlantic Ocean in Truro, Wellfleet and Eastham. Cape Cod National Seashore beaches in the mix include Head of the Meadow Beach in Truro, Marconi Beach in Wellfleet and Nauset Light and Coast Guard beaches in Eastham.

Miller estimated that there are about 30 rip current rescues per season at each of the four Seashore surf beaches. But he said he wasn't aware of a rip current drowning occurring at a Seashore beach in the 37 years he has been on the job, or in the 60-year history of the park.

In 2021, however, a swimmer died after reportedly being caught in a rip current in the ocean off Great Pond on Martha's Vineyard. And there have been close calls in the region, one of which is documented in the new film "Rip Current Rescue," set to debut on Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) stations this summer and also available on streaming platforms.

A segment of the documentary shows what happened in July 2015, when Derrick Johns and his two daughters were swimming at Surfside Beach on Nantucket. One of his daughters had a GoPro camera on a stick, and the footage shows how quickly the situation went from carefree frolicking to life-threatening as a rip current took hold of them.

Derrick Johns used a GoPro stick to help daughter in a rip current

Johns was able to use the GoPro stick to pull his daughter to shallower water, but lost his footing and was swept out to sea by the current. He made the mistake of trying to swim against the surging water and quickly became exhausted.

“I was like, it’s going to be OK for them, but I had nothing left. I had 30 seconds left, and the guy made it to me and dragged me in. I was just basically jelly,” Johns told the Cape Cod Times in 2015.

Plan ahead: Cape Cod Beach Guide 2022

More: Cape Cod beach sticker information 2022

In the documentary, Johns sums up his battle with a rip current this way: "I'm a former Marine, was in the Gulf War and I don't think I can say I was that scared ever over there. Swimming into the current, that's Mother Nature. There's nothing stronger than that, that I've ever felt."

Drowning caused by rip currents can occur "when people pulled offshore are unable to keep themselves afloat and swim to shore. This may be due to any combination of fear, panic, exhaustion, or lack of swimming skills," according to a fact sheet published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the USLA.

But there are ways to better the odds of getting into serious trouble with rip currents, and most importantly, avoiding drowning deaths. Miller urges visitors to Seashore beaches to look at signs at the entrance to beaches that provide daily updates on water and air temperature and surf conditions. It's also a good idea to chat with lifeguards about any hazards that could be in play when swimming.

Here is essential information from a USLA/NOAA fact sheet about rip currents:

Q. What can people do if caught in a rip current?

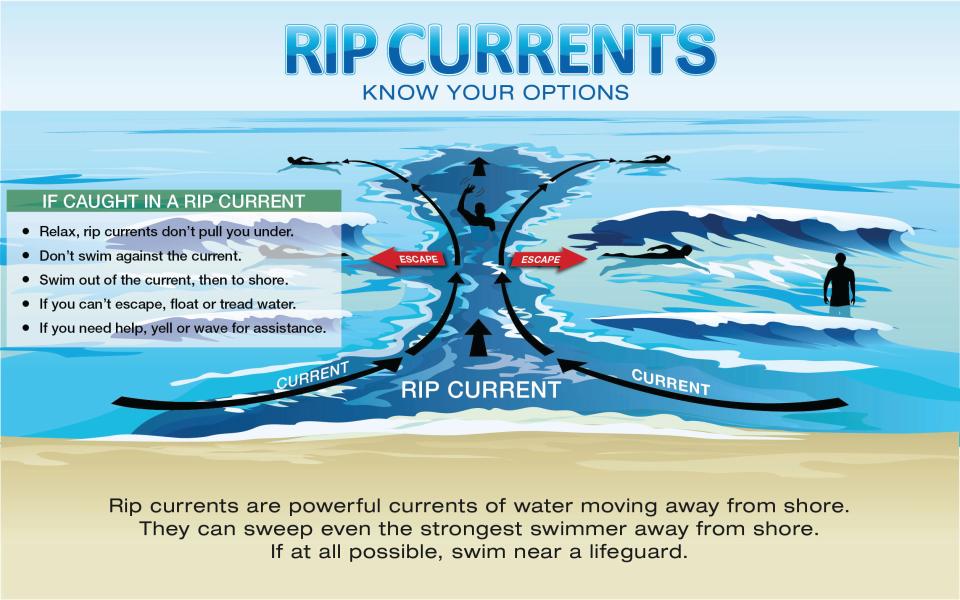

If caught in a rip current: Try to remain calm to conserve energy. Don’t fight the current. Think of it like a treadmill you can’t turn off. You want to step to the side of it. Swim across the current in a direction following the shoreline. When out of the current, swim and angle away from the current and towards shore.

Cape Cod beachgoers: Shark and seal safety guidelines

If you can’t escape this, try to float, or calmly tread water. Rip current strength eventually subsides offshore. When it does, swim toward shore. If at any time you feel you will be unable to reach shore, draw attention to yourself: face the shore, wave your arms, and yell for help.

Q. How can people assist others who are caught in a rip current?

If you see someone in trouble, get help from a lifeguard. If no lifeguard is available, have someone call 911. Throw the rip current victim something that floats – a lifejacket, a cooler, a ball. Yell instructions on how to escape.

Many have died trying to help others. Don’t become a victim while trying to help someone else! Before you leave for the beach, check the latest National Weather Service forecast for local beach conditions. Many offices issue a Surf Zone Forecast. When you arrive at the beach, ask on-duty lifeguards about rip currents and any other hazards that may be present.

Q. How can I identify a rip current?

Signs that a rip current is present are very subtle and difficult for the average beachgoer to identify. Look for differences in the water color, water motion, incoming wave shape or breaking point compared to adjacent conditions. Look for any of these clues: Channel of churning, choppy water. Area having a notable difference in water color. Line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving steadily seaward. Break in the incoming wave pattern. One, all or none of the clues may be visible.

Q. What is a rip current?

Rip currents are channeled currents of water flowing away from shore at surf beaches. They typically extend from near the shoreline, through the surf zone and past the line of breaking waves (the surf zone is the area between the high tide level on the beach to the seaward side of breaking waves).

Seashore partnerswith Cape Cod Healthcare to combine health talks, hikes

Q. How do rip currents form?

Rip currents form when waves break near the shoreline, piling up water between the breaking waves and the beach. One of the ways this water returns to sea is to form a rip current, a narrow stream of water moving swiftly away from shore, often perpendicular to the shoreline.

Q. How big are rip currents?

Rip currents can be as narrow as 10 or 20 feet in width though they may be up to ten times wider. The length of the rip current also varies. Rip currents begin to slow down as they move offshore, beyond the breaking waves, but sometimes extend for hundreds of feet beyond the surf zone.

Q. Are all rip currents dangerous?

Rip currents are present on many beaches every day of the year, but they are usually too slow to be dangerous to beachgoers. However, under certain wave, tide, and beach shape conditions they can increase to dangerous speeds. The strength and speed of a rip current will likely increase as wave height and wave period increase.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Swimming on Cape Cod: How to spot rip currents and get out of one