The rise and fall of the yakuza, Japan's ruthless mafia gangs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Satoru Nomura, the 74-year-old leader of Japan’s most violent yakuza group, was sentenced to death this August, it sent a shock wave through the Japanese underworld.

But the shock probably didn’t come close to that caused by the blast of a hand grenade thrown into a nightclub by members of the Kudo-kai after the owner refused to pay protection money. Nor did it quite match the impact of a two-ton truck being rammed into the home of another person who hadn’t paid his dues.

While Left-wing pundits and legal scholars professed to be astounded at the first case of an active yakuza boss being sentenced to death on circumstantial evidence, those who had suffered at the hands of the Kudo-kai breathed a huge sigh of relief.

‘Yakuza’ is a blanket term for a large number of organised crime groups within Japan – the Japanese equivalent of the Mafia, if you like. There are currently 24 recognised groups and roughly 26,000 active yakuza members in Japan right now. The most dangerous group is the Kudo-kai, located in Southern Japan’s Kitakyushu city.

The group has been involved in a raft of high-profile crimes, including attacking a Toyota factory and firebombing the office and residence of Shinzo Abe (who later became Prime Minister of Japan – Abe’s flunkeys had allegedly failed to pay the organisation properly for its services in defaming a political rival).

The Kudo-kai also bombed the home of the CEO of Kyushu Electric Power Company (he was unhurt). Almost all these crimes were committed to force firms to pay protection money or punish them for not doing so.

Nomura rose to the top of the organisation in 2000. Since then, there have been 114 attacks on civilians believed to have been committed by the Kudo-kai, some never solved. Their particular brand of lurid violence is not something Europeans might associate with the popular perception of polite, ordered Japanese society.

Kudo-kai gangsters have stabbed golf club owners and sliced open the faces of mama-sans (female managers) of hostess clubs who refused to entertain gangsters.

They’ve rammed cars into pachinko parlours and burnt down homes and businesses. They’ve shot dead union leaders and wounded construction company presidents who wouldn’t cut them in on public works projects. They’ve fired bullets into the cars, homes and businesses of those who refused them service. They’ve used guns, blunt instruments, arson and even rat poison.

They have a unique way of doing things: yakuza don’t rob banks with guns; they rob them with blackmail, fraud – and cats. In the 1990s, a faction of 100 members of the Inagawa-kai yakuza lined up in front of a bank near Machida city with stray cats and one-yen coins. They twirled the cats around by their tails to create a ruckus and noisily began to open accounts, depositing only one yen.

They were not doing anything illegal per se and the bank manager got them to leave by promising to make a loan to a company the group was backing. Extorting money without actually ever resorting to brutality is the smart yakuza way. It’s the threat of violence that motivates most people to pay up. With the Kudo-kai, the threat was almost never a bluff.

I have been covering the yakuza since 1992, when I was in training to be a reporter for Japan’s largest newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun. The first story I wrote was about yakuza extorting money from Israeli street merchants working in the area. The first yakuza boss I ever met called me because he was in a bind and thought I could help him out.

It was a strange meeting but it taught me much about how things worked in their world. By 1994, I was assigned to cover the anti-organised crime division of the Saitama police department. I’ve met some honourable yakuza – and am still friends with a few who have retired.

They have been good sources, but they never provide information without an ulterior motive. In general, they are highly functional sociopaths and best avoided.

I wrote the truth about one amoral, double-dealing yakuza boss in 2008 and ended up in police protection for five years because of it. Yakuza are hard to deal with. Every conversation can turn into a fight. A careless word will be seized upon and some will attempt to force you to apologise and then demand compensation for being insulted.

In 2010, one of my better yakuza sources was high as a kite on methamphetamines and in a state of drug-induced paranoia when I went to visit him. The evening ended with him kicking me in the head and bruising my spine, while I probably broke his knee and damaged his larynx.

I didn’t call the police because he was my source. Later we patched things up. He still has a raspy voice and I have trouble sitting still for long periods. It’s an occupational hazard. I’m 52 now. That makes me two years older than the average yakuza. These days, I keep the association to a minimum.

The term ‘yakuza’ is a self-effacing moniker, referring to a losing hand in a traditional Japanese game of card; it essentially means ‘loser’. However, in Western Japan, the gangs refer to themselves as ‘gokudō’ (極道), which translates as ‘the ultimate path’. Japan’s National Police Agency does not use either term, but calls them ‘bōryokudan’ – literally ‘violent groups’.

They are not hidden and are not ‘secret societies’. The yakuza are regulated and monitored but the organisations themselves are not illegal. Each group has its own corporate logo or ‘coat of arms’. This serves as their brand name and adorns their offices and business cards. In Kobe, the Yamaguchi-gumi’s diamond-shaped logo is as well-known as the golden arches of McDonald’s.

Nomura was arrested in September 2014. Due to lack of evidence, he was only on trial for one murder and three attempted murders. The Fukuoka Court (one of eight high courts in Japan) ruled that he had ordered the assassination of Kunihiro Kajiwara, the 70-year-old former head of a fishing cooperative.

Kajiwara was shot four times, once at point-blank range in the head, and died on a Kitakyushu street in 1998. He’d refused to let the Kudo-kai have a cut of a lucrative construction project.

The victims of the attempted murders were a retired Fukuoka Prefectural police captain, who had long been in charge of investigating gangsters (he is now under police protection and cannot be named), shot by Nomura’s men in April 2012 on a street in Kitakyushu; a dentist who was stabbed in the leg and stomach in a parking lot (he was a relative of a former fishery cooperative leader); and a 45-year-old nurse, who was stabbed in the head on a street in Hakata Ward, Fukuoka, in January 2013.

She had overseen a Brazilian wax and penis enlargement for Nomura, and the procedure had not gone well – he felt she had made fun of him and it left him in pain for several days, although normal function of his appendage was apparently unimpaired.

Legal scholars lamented what they saw as the injustice of a death sentence for only one murder but the people who live in Kudo-kai territory were overjoyed. ‘I hope they hang him high,’ one 55-year-old bar owner in the entertainment district said. ‘There was a time when I respected the Kudo-kai and was happy to pay a few hundred dollars in protection money. But those days ended several decades ago. I miss the good old yakuza.’

‘The good old yakuza’ is a bit of a myth. All yakuza groups in Japan claim to be humanitarian organisations – fraternal groups that keep the peace, help the weak and battle the strong. They all claim to ‘never bother civilians’. It’s true that there was a time when the Kudo-kai peacefully coexisted with the community, but since Nomura became the group’s fourth-generation leader, those days are well and truly over. The police and general public are no longer tolerant of their presence.

‘The yakuza aren’t a necessary evil – they’re just evil. Most of them are sociopathic scum. It’s time for them to go – and good riddance,’ says former Fukuoka anti-organised crime division detective, Masataka Yabu. He knows Nomura: he spent years working on the cases that finally caught up with him. One of the first cases he ever handled as a detective involved the brutal murder of one of Nomura’s former rivals, but he could never prove he had a hand in it.

Oddly, for many years, the only place a yakuza boss was ever really held accountable for the crimes of his ‘soldiers’ was in civil court. The power structure of the yakuza made prosecution extremely difficult and Japanese prosecutors, who take pride in their much-vaunted 99 per cent conviction rate, often refused to indict a yakuza without a full confession from the accused.

The prosecutors manage to maintain that conviction rate in criminal courts because they will only take slam-dunk cases. If it’s not a sure win, they won’t indict. It’s something that the yakuza groups, who hire excellent lawyers and former prosecutors to keep them briefed, know well and have used to their advantage.

However, Yabu is right. Times have changed. And so have the yakuza. The most powerful yakuza group in Japan, the Yamaguchi-gumi, located in Kobe, is now over 100 years old. The legal and societal status of the yakuza has evolved since their formation and subsequent emergence as a major force in the aftermath of the Second World War.

There was a period of chaos after Japan’s surrender when many of the victims of Japan’s imperial era – the Koreans, Chinese and Taiwanese – were declared third-party nationals. The Japanese police couldn’t touch them.

After years of oppression, the resident foreigners took advantage of the situation and took revenge. The police were understaffed. The yakuza became an intermediary police force of sorts and the police were grateful.

By the late 1940s, yakuza groups began setting up construction companies, talent agencies, real-estate ventures and other legitimate businesses, along with their illegal businesses such as loan sharking, racketeering, blackmail, unregistered labour dispatch and, of course, gambling.

Every yakuza group has a slightly different structure but they all have some things in common. They are fraternal organisations and no women are allowed to join. A new member pledges loyalty to his ‘oyabun’ (father figure) who is the head of the organisation. The relationship is often sealed with a ritual sake exchange. Anyone can join – if you have a penis – and anyone can rise to the top.

Many of the yakuza are Korean Japanese or members of the outcaste class who faced discrimination in Japan of old. Most groups were – and still are – meritocracies. If you worked hard, paid your dues, or served your time in prison, you could rise up quickly.

Many joined attracted by the prospect of ‘fancy cars, beautiful women, the fear and respect of their peers, and lots of money’, according to one former member. However, the days when yakuza could walk around with their badges on and a business card that struck terror into the hearts of ordinary people have been over for almost a decade. The average yakuza is 50. Young people are not joining.

But the Japanese are still fascinated by the yakuza. They’d like to believe there are outlaw heroes in the world. The Sega game series Yakuza has sold millions of copies in Japan and worldwide. Comic books about yakuza do well, as do drama series. However, the word ‘yakuza’ still strikes fear into the heart of the average citizen, to the point where I’m uncomfortable talking about them in public.

Like many Japanese people, when discussing them I never say the word. Instead, I pretend to draw a scar down from my ear to my chin with my index finger. That gesture means ‘yakuza’; most people of a certain age know exactly what I’m talking about.

The fatal mistake Nomura made in his reign of terror was orchestrating an attack on a retired police officer. ‘There have always been certain taboos in the underworld that were respected. Attacking a police officer – retired or not – was beyond the pale. There was no way that the police were going to let that go,’ says Professor Hirosue, who specialises in criminal sociology and has conducted extensive interviews with yakuza.

A former police detective adds, ‘Nomura is a thin-skinned individual. The police officer they attacked was a great detective and one of the few people that could speak to Nomura face-to-face without flinching. However, one yakuza expelled from the group got him on tape criticising Nomura – and then played the tape to Nomura, who was furious.’

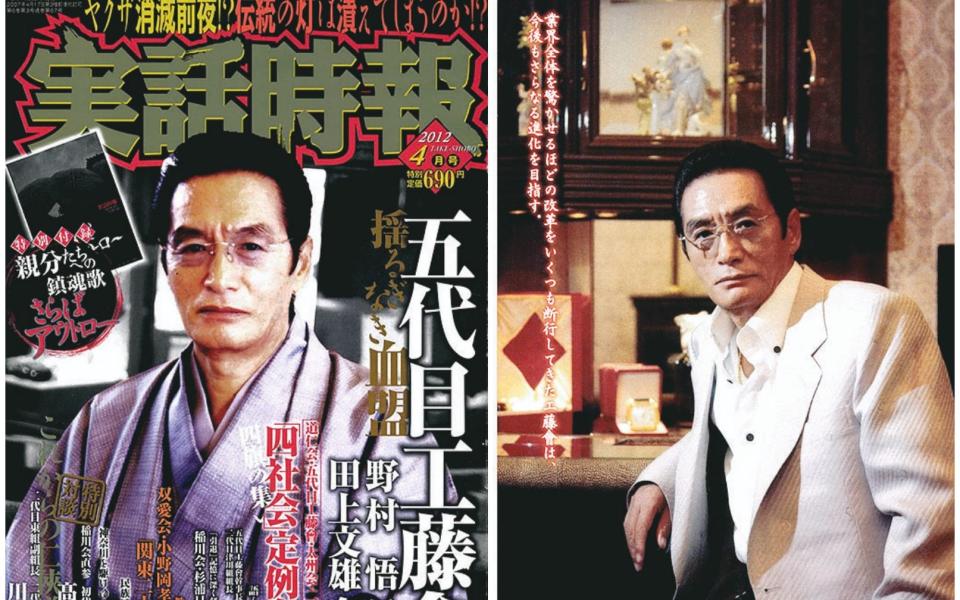

In Nomura’s long trial, a portrait emerges of a man who was seething with anger behind his debonair appearance.

He was not a typical gangster.

Born in Kokura city (part of present-day Kitakyushu) in 1946, he came from a rich farming family and was the youngest of four sons. His father was a shrewd real-estate developer and Nomura never lacked for food or comfort. He was small (5ft 4in) and carried a short wooden sword with him at all times: he was deadly with it. ‘Nomura the Stick’ was his nickname, although no one would call him that to his face. He had a lot of pride and a foul temper.

He began stealing cars in middle school, until he got caught and was sent to a juvenile detention centre. In his 20s, Nomura discovered a love of gambling. He even opened his own gambling parlour; he was a lucky gambler and a shrewd businessman. He not only ran the gambling parlour, he also provided the ATM, so to speak.

He would lend large sums of money to customers at his ‘casino’ and most of them would lose it. He has bragged that he made 20 million yen (£130,000) per night and 200 million yen on his best night.

A high-ranking member of a Kudo-kai gang noticed his success and recruited him. In his memoirs, he insists he never wanted to become a top yakuza boss or even a yakuza at all. But when he met the man who would become his oyabun – ‘godfather’ – at a gambling den, he realised it would be a shrewd move. ‘In order to keep gambling, it was more convenient for me to be a member of a gang.’

Nomura was tremendously successful as a gangster. Under his reign, the Kudo-kai expanded their territory into Tokyo. They earned commissions on almost all construction projects in the area. Nearly every merchant and business paid protection money. The organisation raked in millions of dollars a month.

But unlike his respected predecessor, Nomura was quick to resort to violence. Those who wouldn’t pay protection money or give him a cut of lucrative projects were ruthlessly attacked, as were their family members. In many ways, he was similar to the infamous Yamaguchi-gumi boss Tadamasa Goto, who revelled in sadistic violence, had over $100 million in assets, and at one time was the largest shareholder of Japan Airlines.

Nomura was also extremely wealthy. In 2014, he had the equivalent of $14 million (1.4 billion yen) in his bank account. He is an intelligent individual who appreciates good wine and has a custom-made cellar in his palatial mansion. He was referred to as ‘the Emperor’ by his gang – and treated like one.

Every morning, when he came down from his bedroom, the gangsters would prostrate themselves on the floor in front of him. He never travelled alone. His henchmen escorted him to golf in the afternoon and expensive clubs in the evening. He was a lavish tipper and paid generously for the welfare of his wife, numerous ex-wives and their children.

Members of the Kudo-kai jailed for the organisation (the ones who didn’t confess) were rewarded with promotions upon being released. During their time in jail, Nomura made sure their families were provided for. He took care of people. But what made him successful was the brutal way in which he took care of his enemies.

His brilliant use of the carrot and the stick ensured that those arrested never ratted him out. Keep your mouth shut and you get rewarded; rat out your bosses and you will become familiar with the Japanese proverb, Dead men have no mouths.

Nomura was quiet and respectful during his long trial, but when the presiding judge Ben Adachi sentenced him to death, he showed his true colours. ‘I asked for a fair decision and a fair trial,’ he growled. ‘This isn’t fair. You’ll regret this for your whole life.’

The implication was that Judge Adachi might not live very long. He is now under police protection and Nomura has appealed the decision. He is unlikely to win. If he loses, he’ll be hung, with little or no notice. He might be able to continue to appeal for many years – but not for ever. The majority of the Japanese public supports the death penalty and there is no sympathy for the man.

The only real question left is, which will die first: Nomura or the organisation he led for nearly two decades? When that is answered, the thousands of people terrorised by the Kudo-kai will all breathe a little easier.

Jake Adelstein is the author of Le Dernier des Yakuzas (Marchialy, £17.50)