He risked his life to prevent a meltdown. Now, a hero of the TMI accident gets recognized

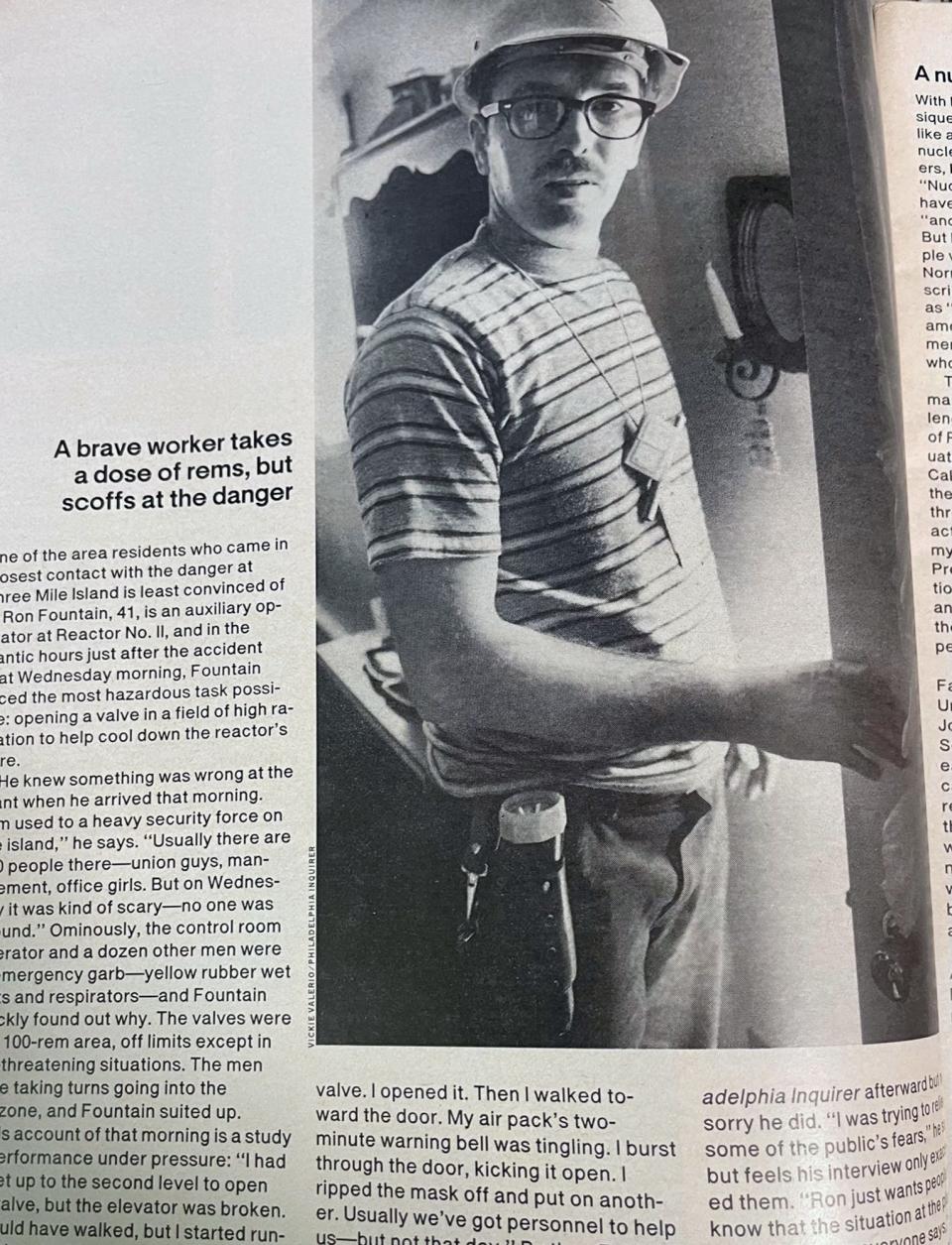

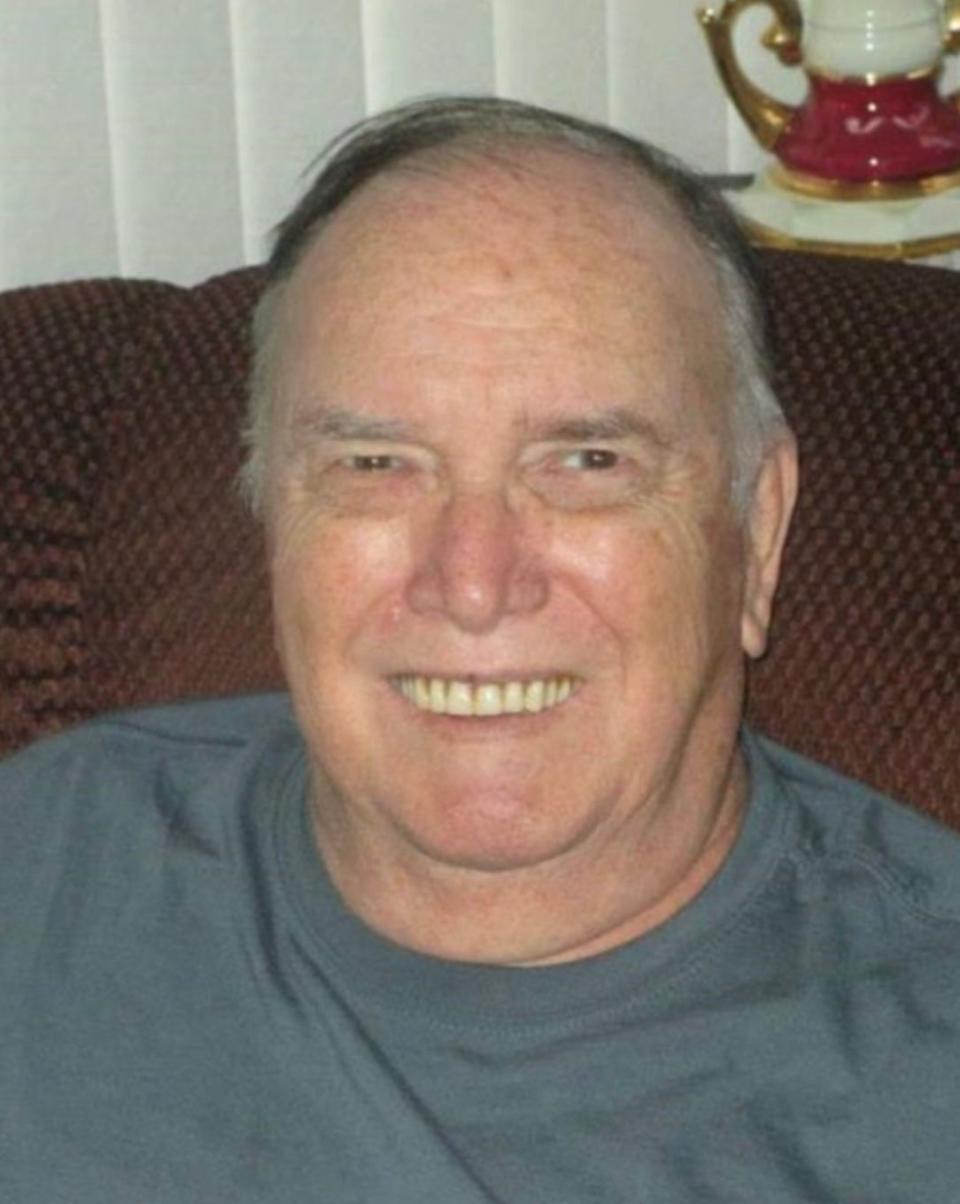

In March 1979, Ron Fountain was an auxiliary reactor operator at Three Mile Island.

He came to the job by a circuitous route. He had previously worked as a maintenance mechanic for an airline and a supervisor in a cough drop factory. Before training as a reactor operator, he worked as a janitor at TMI.

He worked his usual shift on March 27 that year, clocking out at 11 p.m. and heading home to bed. Not long after he drifted off, his wife shook him awake.

Someone from the nuclear generating station control room called. Something had gone wrong. And Fountain had to report to work; it was an all-hands situation. No explanation was given. Fountain dressed ― blue jeans and a flannel shirt ― and drove back to the island. One thing that seemed odd: The voice on the other end of the phone sounded muffled, a mystery that soon would be solved.

When he arrived at about 4 a.m., he noticed something was amiss. The facility, usually a hive of activity, was eerily quiet, “a ghost town,” he would say later. “He knew as soon as he pulled up that something was going on,” his 56-year-old son, Kevin Fountain, said.

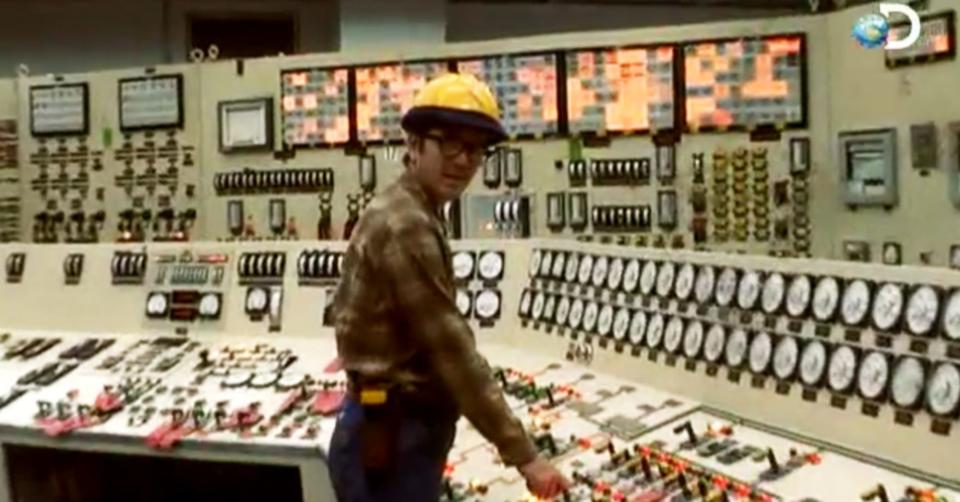

The scene inside the control room, a radiation-proof bunker in the heart of the plant, was different. Usually, he recalled later, there were four operators monitoring the horseshoe-shaped console housing the various switches that controlled the nuclear reaction within Unit 2’s containment vessel.

That early morning, there were about 10 reactor operators crammed into the control room, all wearing respirators. One of them tossed a respirator to Fountain, who responded, “What the heck?” He had never worn one during his tenure at the plant.

The operators struggled to gain control of the reactor. At one point, they needed someone to venture into the guts of the plant to unlock a valve that would feed needed cooling water into the reactor vessel.

They turned to Fountain.

And with that, he became one of the unsung heroes of what would come to be known as the worst nuclear accident in American history.

'Erased from history'

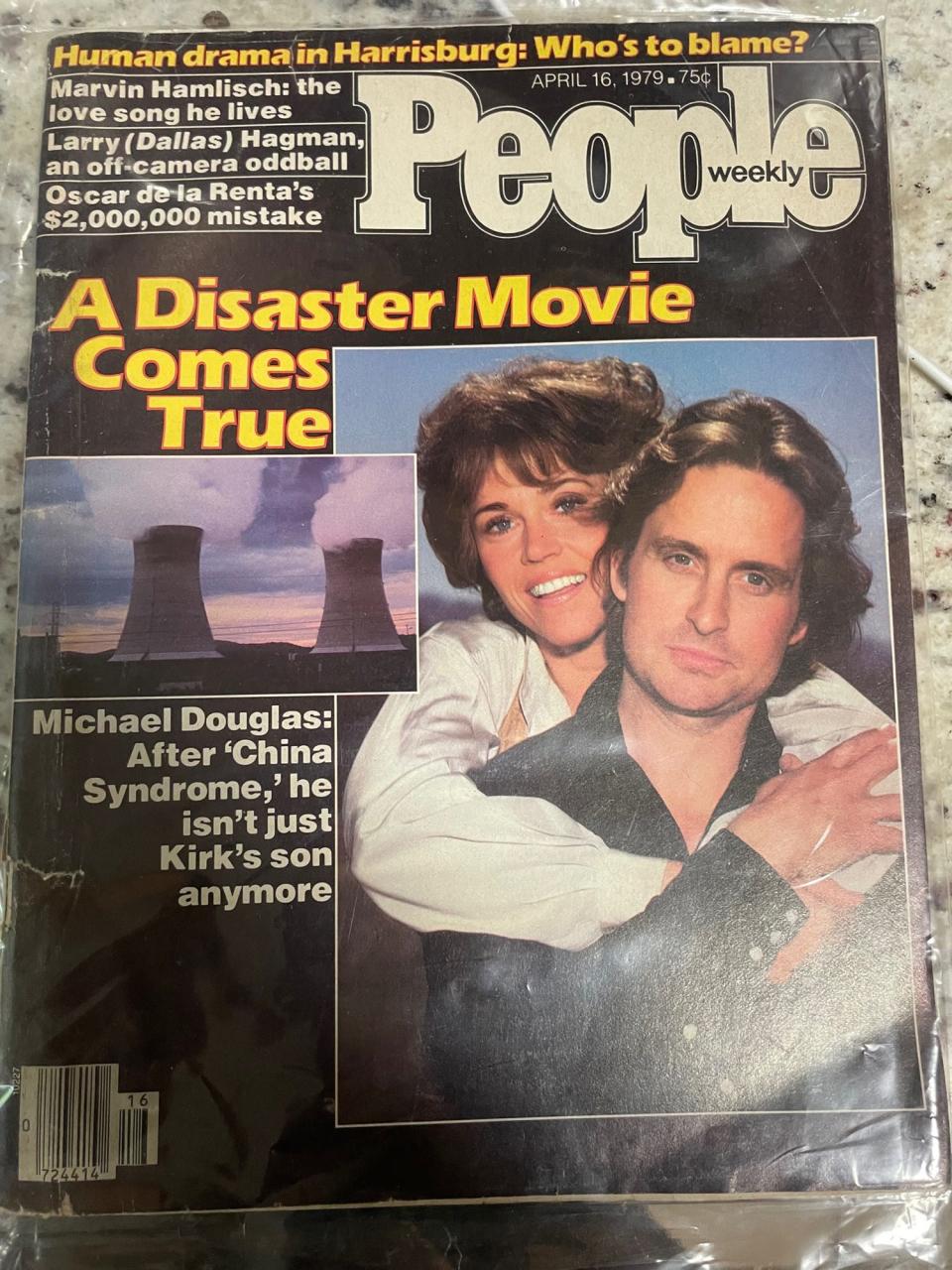

It’s been 44 years since the Unit 2 reactor at Three Mile Island nearly melted down. Yet, mention of TMI still evokes strong memories among those who lived through the accident, the fear, the anxiety. More than 100,000 people evacuated the area surrounding TMI ― a number that included Fountain’s family ― to escape the invisible terror of radiation.

TMI is closed now, a concrete memorial to the nation’s nuclear-power program.

The accident wasn’t as bad as it could have been ― not as catastrophic as the explosion at Chernobyl in the then-Soviet satellite of Ukraine or the disaster at the Fukushima plant in Japan.

Part of that can be attributed to Fountain’s actions that day. And while he did speak to reporters a couple of times over the years ― once to the New York Times and again in 2011 to Newsweek after the Fukushima meltdown ― his role in the accident has been relegated to obscure government documents chronicling the accident.

A 2022 four-part docuseries streamed on Netflix ― “Meltdown: Three Mile Island,” which was a hit and was nominated for an Emmy Award for outstanding historical documentary ― did not mention Fountain’s role in the accident.

And that rankled Kevin Fountain.

“I don’t know how he was erased from the history,” Kevin Fountain said. “He deserves recognition.”

From a janitor to a hero

Ron Fountain’s journey to history began in Canada.

His father served in the Canadian military during World War II. (Canada entered World War II on Sept. 9, 1939, eight days after Hitler invaded Poland. The United States didn’t become involved in the war until after the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941.)

When his father returned from the war, Kevin Fountain said, he suffered from what was then known as “shell shock,” now diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder. His father couldn’t work so Fountain dropped out of school in the ninth grade to help support his family and supplement his mother’s income from her job at a munitions factory.

He sold meat pies that his mother baked, an attempt to become the Mrs. Smith’s of Canada, riding his bike on his sales routes. When he was old enough, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, training in aircraft maintenance at the base in Chatham in New Brunswick, serving a four-year hitch.

After his parents divorced, his mother emigrated to the United States, settling in New York. Fountain, out of the service by then and living in Toronto, visited his mother in New York and decided to stay, getting a job as an aircraft mechanic for now-defunct Pan Am Airways. Once, Kevin Fountain said, he found some folded papers in a seat-back pouch. It appeared to be a handwritten speech. He read it and threw it away. He learned later the speech had been written by a Massachusetts senator named John F. Kennedy.

A friend at Pan Am had family living in Mohnton, just south of Reading, in Berks County, and invited Fountain to visit his hometown. There, Fountain met a woman and decided to quit his job at Pan Am and move to Pennsylvania. He worked as a supervisor at Luden’s cough drop factory, but that was too stressful. He then took a job at a Carroll’s fast-food restaurant, but that wasn’t less stressful.

His father-in-law and other family members worked for Met-Ed and suggested he get a job at the new nuclear power plant along the Susquehanna River, just south of Harrisburg, called Three Mile Island.

He started out as a janitor. Later, after he passed an aptitude test, he enrolled in a two-year training program to become a reactor operator. It may seem odd. Many of the reactor operators at TMI were veterans of the nuclear Navy or had higher education. Fountain, though, had a knack for the job. “A lot of people think he only had a ninth-grade education,” his son said. “But he was a voracious reader, and he was smart. Smart people get elevated.”

And so, at 41, he was an auxiliary reactor operator when something went wrong inside Unit 2.

'Just a family man'

As operators struggled to gain control of the reactor, they realized they needed to get water into it to cool it down and avert a total meltdown.

Fountain knew the plant and the team asked him to venture into its bowels to open a stuck valve to allow needed cooling water to flow into the reactor. Later, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission would ask him why he agreed to venture into a part of the plant where radiation readings were spiking. He said he didn’t think about it. “We had to save the plant. We didn’t think about saving our own lives," he told Newsweek in 2011, a piece that was republished by the Daily Beast in 2011.

Outside the control room, Fountain began to hyperventilate and nearly passed out. He slumped against a wall about 30 feet from the valve. He was not a religious man, his son said, but he asked God for help. He made it to the valve and opened it. The water cooled the reactor’s core and helped operators gain control.

After he opened the valve, he took a decontamination shower alone, still dressed, and then left the plant, driving home to his family’s empty house near Elizabethtown.

He worked in his garden to calm his shattered nerves.

In April 1979, he told The New York Times, “I’m just a family man and a guy who likes doing his job.”

Later, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, as had a number of other his co-workers at TMI. A few years later, he moved to Arizona and worked as a quality assurance manager at the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station near Tonopah, about 45 miles west of Phoenix.

'Saved hundreds is not thousands of lives'

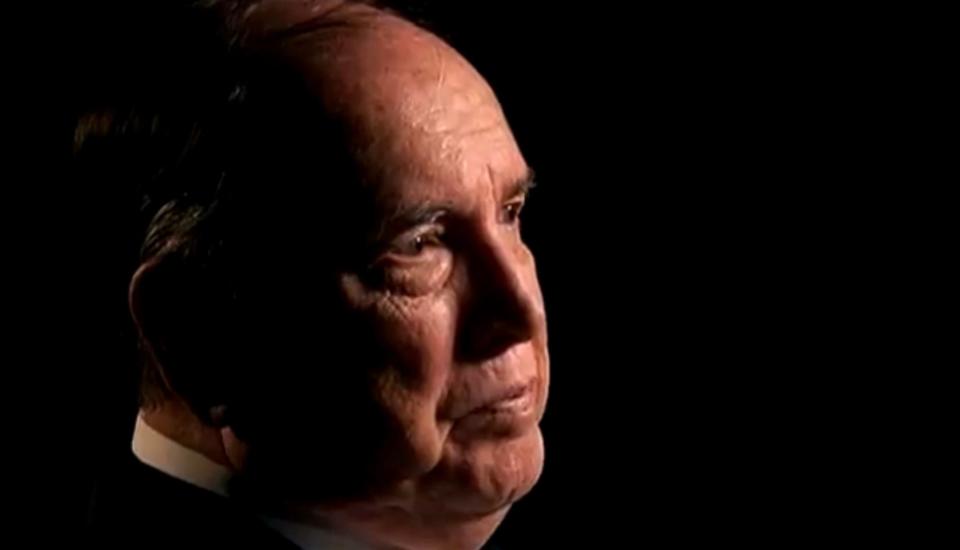

Fountain died on March 2, 2020, 23 days shy of his 82nd birthday.

When the Netflix documentary came out, his son was upset the filmmakers did not give his father credit for his role in averting the accident. He contacted the film’s director, who told him the producers tried to get in touch with Fountain, calling him twice, but never receiving a reply. The reason for that was simple: By then, Fountain had passed away.

“I was fuming,” Kevin Fountain said.

His son wanted recognition for his father. He saw a piece of mail from his state representative, Berks County Democrat Mark Rozzi, on his table and contacted his office. (Kevin Fountain lives in Mt. Penn in Berks County and volunteers at the Berks History Center.)

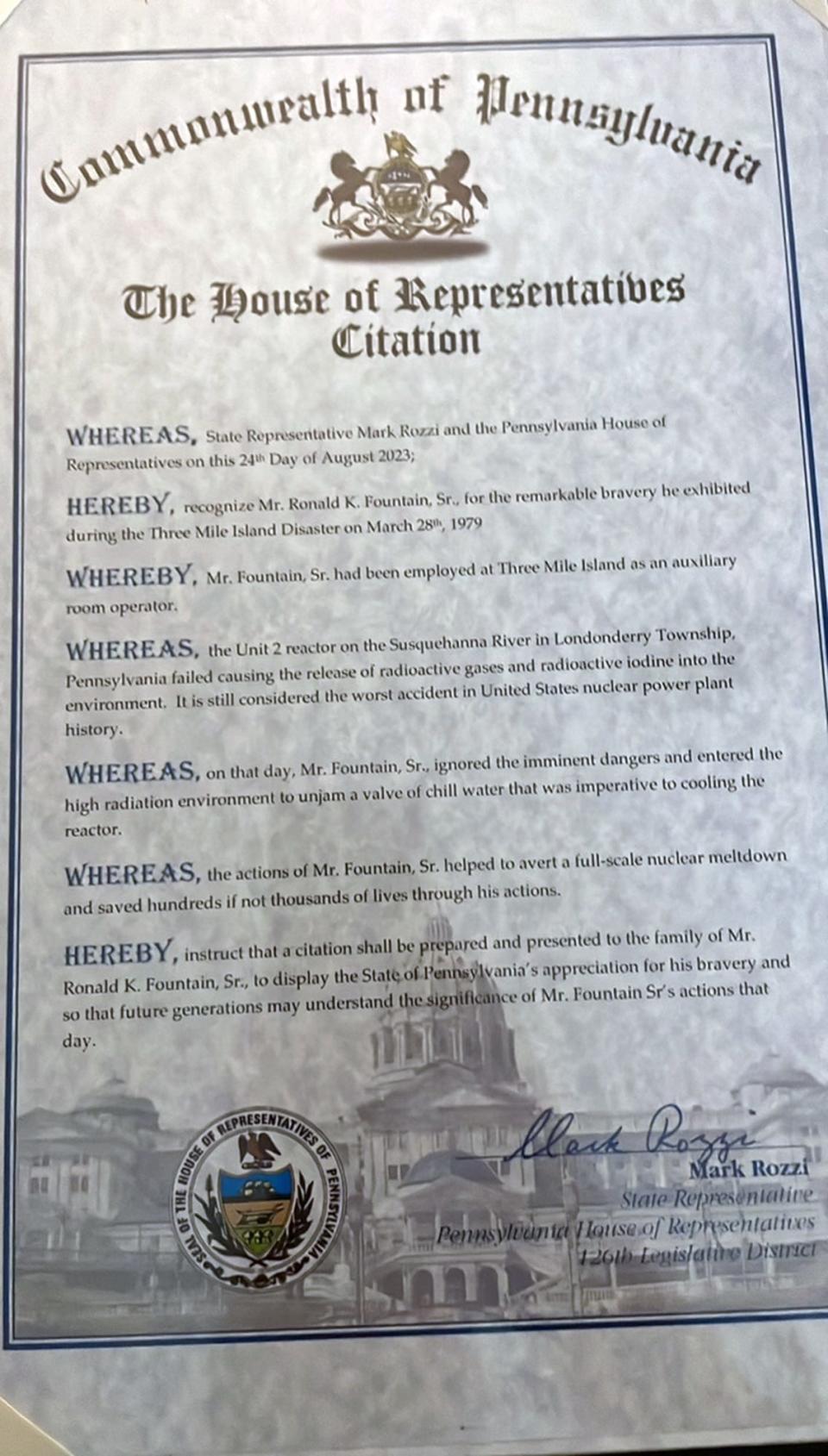

On Aug. 24, a citation lauding Fountain’s “remarkable bravery” passed the state House.

Fountain, the citation read, “ignored the imminent dangers and entered the high radiation environment to unjam a valve of chill water that was imperative to cooling the reactor.”

It continued, “The actions of Mr. Fountain Sr. helped to avert a full scale nuclear meltdown and saved hundreds if not thousands of lives through his actions.”

His son was pleased but is not finished.

“Whatever I do the rest of my life,” he said, “I want to make sure that my dad’s legacy continues.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a York Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at mike@ydr.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: A hero of the TMI accident gets recognition, 44 years later