How to Make a Road Trip in a Porsche 911 GT3 RS Miserable

This story originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Road & Track.

Midnight. Atlanta, Georgia.

Camden raised an eyebrow. "Aren't we just making a 911 R?" Our car was a GT3 RS. The R is basically that minus a rear wing.

I had just unbolted our wing and packed it into the chase van.

I shrugged. "Sort of? But an RS is lighter and faster and whatnot. And now with janky cardboard Moon discs on the wheels!" Camden sighed.

Camden Thrasher is one of R&T's contributing photographers. He generally reacts to human encounters as if he was born on another planet and is perpetually unimpressed by our customs. Camden is also the sort of unflappable head that tends to be useful in unknown territory, which is why I brought him along. We were diving into an experiment.

The EPA says a Porsche 911 GT3 RS, driven normally, will see 19 mpg on the highway. Our car, a neon-green 2019, was not about to be driven normally. It was on loan from Porsche and wore the usual host of options. Chief among them: the ($140!) 23.7-gallon "touring" fuel tank, 6.8 gallons more than standard. Six-point-eight extra gallons stashed under the filler cap of a 520-hp track rat with fixed-back carbon buckets and enough spring rate to hold up Cleveland.

Porsche track specials tend to be practical on long trips: half sports car, half supercar, decent luggage space and visibility, endurance-racing pedigree . . . You know the rest. You may not know that the current GT3 RS is about to leave production.

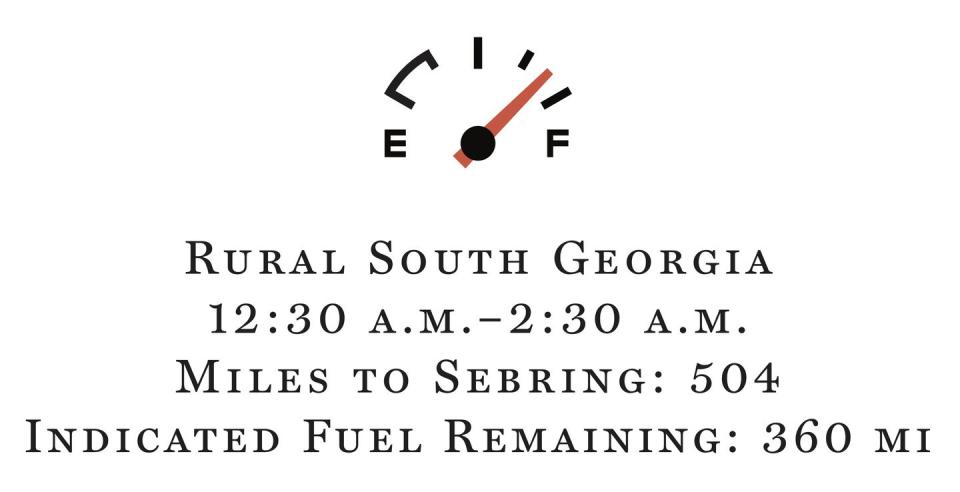

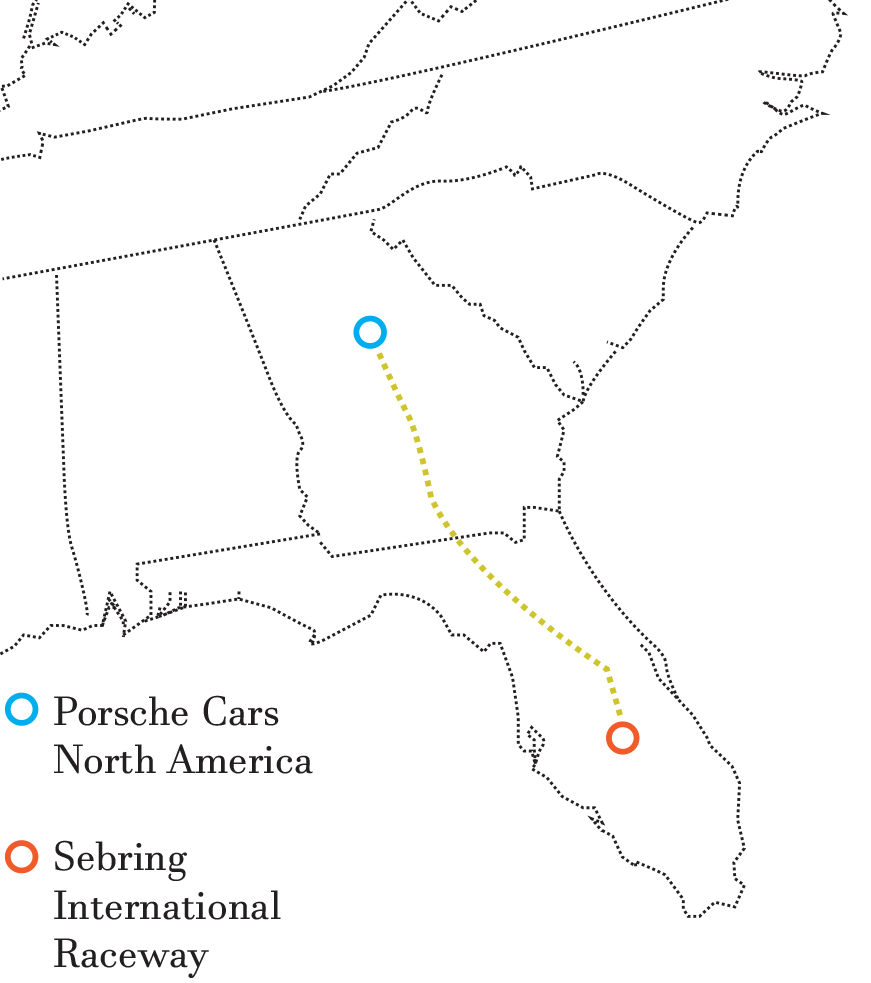

Departures require a send-off; departures of respected giants, more so. And so it was midnight, in Atlanta, near Porsche's North American headquarters, and the car was wallpapered with masking tape. Over body seams and downforce vents, capping bumper nostrils and hood ducts, piled into the tray beneath the wipers. All ostensibly for drag reduction, like that missing wing, but also to lend a sense of purpose. Twenty-three-point-seven gallons of gas multiplied by 19 mpg equals 450 miles of range. Porsche's Atlanta facility is 504 highway miles from Florida's Sebring International Raceway, and Sebring is home to the most famous 12-hour endurance race, a Porsche touchstone.

I figured we could connect those dots on one tank of gas if we left late at night—avoiding traffic and heat, hypermiling on the interstate, treating throttle like poison. It was a less than serious task, which made me happy in the planning, because the world has no shortage of people who take Porsches too seriously. IMSA, the 12-hour's sanctioning body, agreed to give the GT3 a parade lap of the track as a symbolic trip closer. We timed the whole thing to end during ramp-up for the annual 12-hour, in early March.

We brought a chase van, in case my math was wrong and the car ran out of gas. The van was driven by Brian Silvestro, R&T's long-suffering 24-year-old social-media editor. Brian did me a favor and made the Moon discs late at night, cutting cardboard in a dark parking lot. When he finished the last disc and zip-tied it to the wheel, I patted him on the back.

"These are great! And they're almost certainly maybe possibly going to work."

Brian sighed. "How close," he asked, "can you draft the van?"

The 2019 GT3 RS represents everything Weissach can tell you about making a rear-engined, naturally aspirated road car go quickly. The roof is magnesium; much of the body is carbon fiber. The rear wheels steer themselves during lane changes and cornering. The engine, a 9000-rpm, 4.0-liter flat-six, is distilled Mulsanne Straight.

We did not, technically speaking, need any of that at 50 mph.

We lurched out of Atlanta just after midnight, skulking south on the interstate and dabbling in speed math, playing with throttle and speedometer in search of economy and something like pace. Porsche's trip computers are remarkably accurate, so we leaned on the digital dash for range, average speed, and a rolling stab at instant fuel economy. (Measuring the latter: Reset mpg readout, hold a speed for a few miles, reset again, repeat.) The car ran as high as 32 mpg sustained, as low as 21. Turning the A/C off saved a single mile per gallon. Fifty mph ended up the best compromise, giving an indicated 27 mpg; 55 cost us one mile per gallon over that, and 60 cost us two.

I briefly wondered if the tape and cardboard were helping, then decided I didn't care, because it made me cackle. Camden asked if we should overinflate the RS's Michelins—Pilot Sport Cup 2s, basically DOT-legal race rubber—to reduce rolling resistance. No, I said, it would be bad form to trash one of the best tires in the world, crown-wearing its center from overpressure, to gain a mile or two per gallon.

Hypermilers are incredibly odd people, I preached. Those jerks would ruin a Cup 2; I will not.

All that experimenting should have taken the better part of an hour, chewing up miles and watching the numbers, but it made me feel like Mr. Science, so I stretched it to two. In a quiet moment, I announced that we would also leave the radio off, because you do not win Sebring to Parliament-Funkadelic. Camden nodded, a yes-doctor nod, then descended into a squinty-eyed staring contest with the windshield. Presumably because his inner song dictated it.

A car built to vaporize a 130-mph corner is almost destined to be a snooze in a straight line at 50. Traffic treated us like a cone in a glacial slalom. In seventh gear, in the slow lane, on mostly straight highway, with the windows up, the Porsche might as well have been dead. There was no real engine noise or steering feel, none of the stuff the car is famous for, and it held course on less than a finger. I spent the better part of an hour trying to imagine how much work went into a lap of Sebring in the late Sixties, when 911s raced on skinny tires and the model was young enough to still be a new notion. The road crawled by in the kind of agonizing motion that makes you reconsider the meaning of distance and the wrinkles in your underpants.

"Camden," I said.

"Yeah?"

"This may have been a terrible idea."

He was silent for a moment. Then a knowing chuckle.

"Well . . . yeah."

Somewhere outside Macon, around two in the morning, the slow wormed into my head. It made little tracks, chewing up bits of brain, poking around and looking for a way out. Fireworks spat across my eyelids on each blink. Slow became not so much a temporary condition as a place on the map, a noun, a verb, a foreign language. The feeling resembled the strange mania of any long drive but was compounded by the fact that the car took nothing from me, needed nothing, came just short of driving itself. Input served only to avert action—steer but don't! Fifty on the speedometer, not 51! My foot hovered over the throttle, rarely touching it, like a threat. (Cruise control seemed like cheating. Another self-imposed no-no.)

Eighteen-wheelers went by every 10 seconds or so, a cacophony of wind and tire howl. (Silence, SCREAMING TRUCK NOISE, silence.) Hills were somehow slower than level ground, a chance to count the seconds between seconds, an interminable inhale before the downhill exhale that followed.

By 3:00 a.m., 50 mph had produced a sustained 27-mpg average. The efficiency was eerie and unexpected. Fifty mph in seventh gear in a GT3 RS is 2000 rpm, and 2000 rpm is 22 percent of 9000. If you do 22 percent of anything, did you really do it?

Twenty minutes later, the indicated range to empty exceeded the nav system's mile count to Sebring. The numbers should have been life-affirming—We were going to make it!—but traffic had grown all-consuming. Each car that passed came to feel like a slap in the face. We were passed by one of those giant and impossibly slow tandem-trailer UPS trucks. We were passed by a Ford F-350 towing another F-350. We were passed by every girlfriend I had ever broken up with, every race I'd ever lost, every book I never finished (Look! In that Honda! A copy of Infinite Jest!). We were passed by an old Taurus with a cracked rear bumper and a little old lady at the wheel, hanging on for dear life at 54 mph.

It occurred to me that the only way to make a GT3 RS miserable is to keep it from being a GT3 RS. Chain it to the right lane, like a blue-hair Ford, so it can't rip-snort into the distance.

"This feels like a clogged toilet," I said.

Camden was in the middle of a silent conversation with a bag of candy or jerky or something. He looked over. “"Huh?"

"Einstein said time is a river. We all float in it." I smacked the wheel. "This isn't a river. This is a clogged toilet."

The instruments floated in and out of focus. The dash clock said 4:30 a.m. Then 2:00. Then 5:00. Camden suggested slowing to 40 mph, to squeeze out more range.

Inexplicably, Georgia continued.

The sun came up around 5:00 a.m. or 8:00 or noon, light dappling the dash and warming the car. Buoyed by vitamin D, I didn't so much notice as regain at least half my will to live. The rising sun painted the sky the sort of orange you only see in movies. I had spent an hour on that highway, just before dawn, thinking about how we tie stories to the appeal of speed. Ferdinand Porsche built some of his first cars in a barn, and less than a generation later, his family pointed his company at Le Mans with little more than some fiberglass bodywork and a bit of math. If you know even an ounce of that history, it helps to make a 911's guttural, raspy exhaust note sound somehow iconoclastic, even though the car is no longer anything of the sort. But the noise fits the story and the story fits the sound that the car makes in your head. How do they do that?

The highway did that thing where you blink and 25 miles disappear.

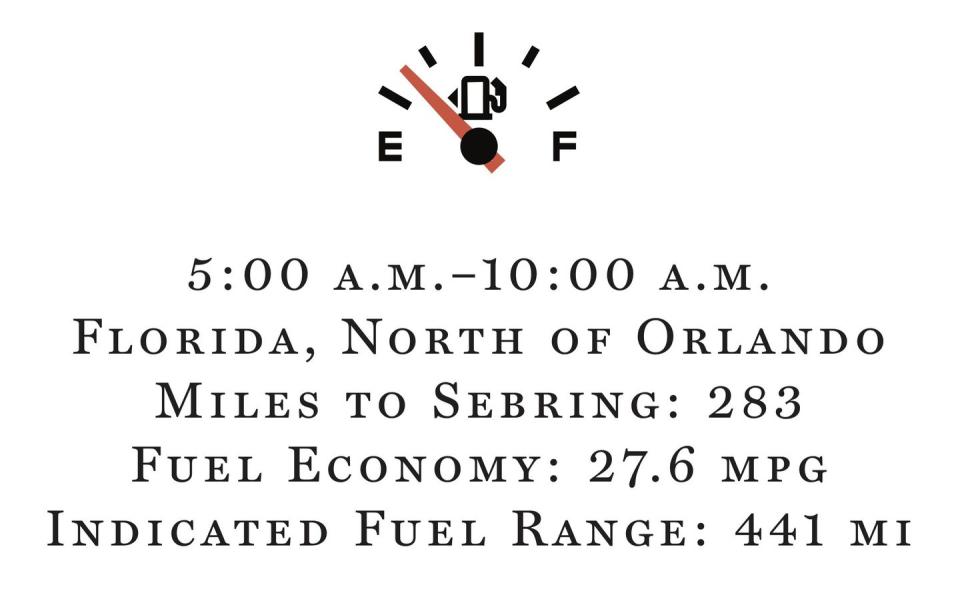

Near exit 427, in Lake City at 6:00 a.m., the RS showed 356 miles of available range and three-quarters of a tank. The nav said we had four hours and 15 minutes left. I decided to push, on the grounds that every endurance race I've ever run has been a funky combination of long planning and last-minute improv. Our cruise nudged up to 60 mph. Then 65. Then, maybe, to more than 100 for a moment, a 9000-rpm run in third, that whoopy-screamy TIE-fighter yell out the pipe. The universe smeared into a delayed-gratification mishmash of space and time and a weird hallucination of 935s and 901s and 917s and 919s, all drafting in a train at Le Mans.

The math seemed impossible: Extrapolate, and a GT3 RS at 55 mph—once the national speed limit!—might see around 650 miles on a tank. Does anyone else ever wonder why our vast, fun-loving nation saw the progress of the 20th-century automobile and decided to limit the country's roads to 55 mph, while the wee and notoriously uptight land of the French met the same general moment in history and said, "Screw it, let's keep closing down country roads and balling around in race cars as fast as we can?"

Masking tape fluttered on the fenders, pulled loose by wind. We were still hours from Sebring. I felt good and broken and warm. The fuel gauge hovered around a quarter tank. It looked like enough.

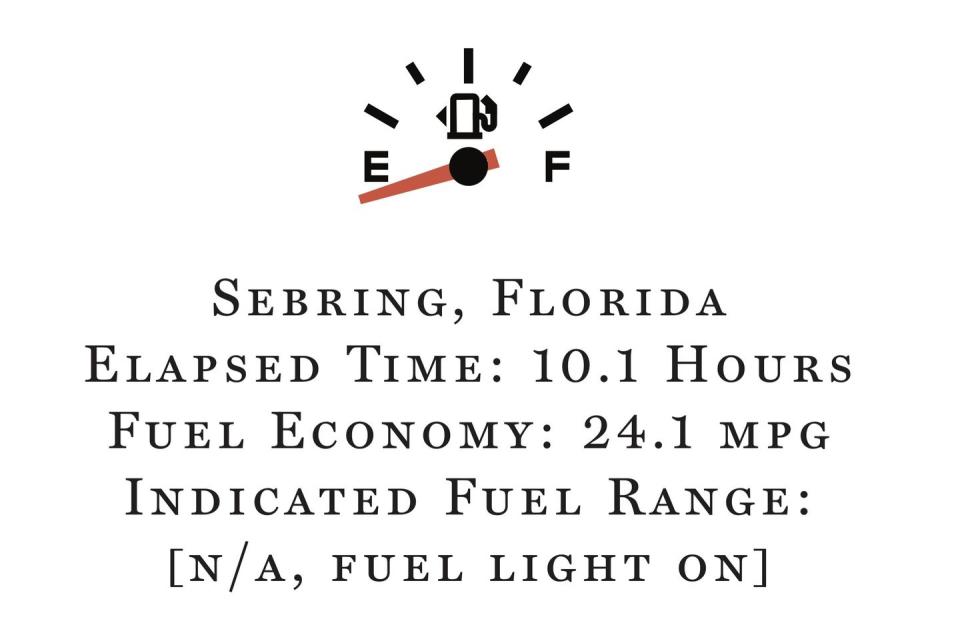

Sebring is a tiny lakeside burg, 85 miles south of Orlando, little more than a main drag by the water. The 12-hour takes over the town for just a few days a year. When we arrived, the place was in full swing, bunting and tourists, the race three days away. The fuel-reserve light was on, a small yellow graphic on the digital dash. I had driven like a hormonal jerk for the last hour, burning high-test as quickly as possible, trying to empty the tank. It had become deeply important to run dry as we rolled into town, for the sake of symmetry.

We ripped off the tape, bolted the wing back on, and drove to the track in production-car drag. Central Florida is flat and sticky, and Sebring is no exception, a surreal racing oasis parked on land only geologic eyeblinks past swamp. Our parade lap came between practice sessions for the 12-hour, surrounded by the circus of a professional race and capped at 40 mph by IMSA. That speed was more than 10 mph slower than the 51.7 mph averaged by the Porsche over 10 hours on the highway. We rolled onto the track after a group of prototypes finished a short practice.

Pro drivers tend to like that place. They say Sebring makes them work—the track is mostly concrete, built decades ago atop the bones of an airfield. The corners are pockmarked and abusive, bumpy enough to send prototypes pitching and three-wheeling past the stands at more than 100 mph. Over a single slow lap, in a road car that can feel leashed in at a buck fifty, it seemed like a place you would go when the rest of the world feels too sensible and easy.

I walked over to the front straight, under a tall set of bleachers, and listened to a few 911s barrel through a timed practice. The noise echoed in waves, bouncing off concrete and walls, the cars in their natural habitat. It was loud and grating and perfect. And for the first time in hours, I wasn't the slightest bit tired.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos