Rob Rinder on October 7 attacks: ‘The paramedic saw headless bodies and heard terrorists laughing’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was 5am when Rob Rinder touched down in Tel Aviv. The airport, usually bustling with life, was eerily quiet – “a ghost town”. He headed towards Sderot, a city by the Gazan border, just an hour away. “The massacre was so close to everyone in Israel – not just emotionally, but physically, too,” he says.

Britain’s much-loved broadcaster, barrister, former Strictly quarter-finalist and author was in Israel to visit first responders from Israel’s ambulance service, Magen David Adom (MDA), meaning the Red Star of David. Accompanied by the chief executive of the British fundraising wing of MDA and a cameraman, his mission was to capture the stories of those who helped save lives on October 7. He’s no hero, he insists, but admits he didn’t tell his 70-year-old mother, Angela, about the trip until he was home, for fear of worrying her. His brother Craig, though, was given the heads-up. “I have the unconditional support and love from my family which, of all of the privileges in life, is the most important one,” he adds.

Rinder, 45, is no stranger to Israel: he spent two and a half years working with “a community of courageous colleagues” to make The Holy Land and Us – Our Untold Stories, a two-part BBC documentary exploring the stories of both Palestinians and Jews following the establishment of Israel, including some of his own family. It was made with “a great deal of time, heart and passion”, he tells me (indeed, the documentary is shortlisted for Best Specialist Factual Programme in the 2024 Broadcast Awards).

He is also familiar with conflict – he was in Sierra Leone at the civil war’s end to help teach non-violent debating skills (the head of his chambers was the Chief War Crimes Prosecutor at the time) and two years ago he went to the Ukraine border to interview those fleeing from the east. But this, he says emphatically, “is different”, adding, “There’s denial of this massacre happening in real time, and there’s an increasing and truly malignant metastasisation of anti-Semitism.”

His maternal grandfather, Morris Malenicky, was a Holocaust survivor, while last year, Rinder, alongside his mother, received an MBE for his work in Holocaust education. Rinder’s acclaimed BBC documentary series My Family, the Holocaust and Me is now being used by UCL’s Centre for Holocaust Education in schools. For Rinder, the rise in anti-Semitism is personal and “deeply disturbing”.

We discuss some of the experiences Jewish people have shared with him over the past two months – teenagers being racially abused on the streets, adults being ostracised by colleagues at work, children being bullied at school. And also the online hatred. “Whether it’s being called ‘dirty Jew’ or a ‘Zionist shill’ – what I thought was only in the darkest recesses of society, is coming out in the public sphere.”

He tells me about a conversation he’d recently had with a reporter for a major American television network.

“He’d interviewed survivors from a kibbutz and showed me messages he’d received from people claiming that those in his reports were actors. I’ve grown up in a family with a Holocaust survivor. I’ve spent time trying to teach about the dangers of anti-Semitism. But here, my friend was warning me that it has reached horrifying new levels.”

Rinder grew up in a working-class community in Southgate, north London. His father was a black-cab driver, and his parents divorced when Rinder was young.

“It was rich in love if not in other things,” he says of his childhood. He was brought up to believe that “nobody gets to write your narrative” – a spirit he credits to Morris, his Lithuanian grandfather.

Rinder had always had a passion for theatre, but at Manchester University, studying politics and modern history, he discovered debating, which brought him to law. He was called to the bar in 2001, taking on court cases involving bribery, corruption, fraud and manslaughter. In 2014, he was asked to front his own reality courtroom drama, Judge Rinder, the ITV version of America’s Judge Judy.

He puts the career pivot down to “a series of random incidents”.

In his spare time he wrote scripts, and he wrote one for a different reality-based show (which never went ahead) that led to a meeting with a producer in search of a TV “judge”. He was a natural and the show became cult daytime viewing.

“Unexpectedly, it just captured the imagination.” Rinder now fronts the BBC’s Amazing Hotels: Life Beyond the Lobby, with Monica Galetti (a festive episode airs on Christmas Eve), and had another history documentary on Channel 4 last month. And, drawing on that legal experience, his second novel, The Suspect, is out next summer – his first, The Trial, came out earlier this year.

The year before his television career took off, Rinder had tied the knot with fellow barrister Seth Cumming. (His university friend Benedict Cumberbatch officiated at the Ibiza ceremony.) But after four years of marriage and 11 years together, the couple amicably split.

When we chat over FaceTime, Rinder is backstage at the Cliffs Pavilion, in Southend, rehearsing for his panto role as Captain Hook. He’s just flown in from Rome (filming a future project he can’t disclose), but his mind is very much back in Israel. “I felt that the response to this denial and everything that goes with it had to be to listen. And who better to listen to than the paramedics of MDA, Israel’s emergency ambulance service,” he says. “These people have no incentive but to save lives and to run towards danger – the very best of humankind.” MDA was established in 1930 by a Jewish doctor as a medical volunteer service, but it was only in July 1950 that MDA officially became Israel’s national emergency service. Fast-forward to 2023 and the organisation has about 1,500 permanent staff and 27,000 volunteers, with approximately 10 per cent of MDA’s income still funded by charitable international donations.

Its workforce reflects the nation it serves and Israeli society as a whole, so includes Jews, Muslims, Christians and others. Today, MDA is in urgent need of funds and hopes that Rinder’s powerful video interviews, screened at charity events on social media, will help. The lives of 11 MDA paramedics were lost that morning, along with 12 emergency vehicles.

To capture personal testimonies, Rinder journeyed south from Tel Aviv with a videographer. Rinder shows me one of the videos – it packs an emotional punch. The stories speak for themselves, but Rinder’s sensitivity and empathy on screen is very moving.

In Sderot, less than a mile away from Gaza, there are only 15 seconds between the sound of sirens and rocket impact, hence the need for bulletproof vests. More than 200,000 Israelis have been evacuated from border towns as Hamas rockets continue to fall. Out of the window, “it was those outward vestiges of modernity that struck me – the things that superficially seem to protect from inhumanity and horror – a McDonald’s, a supermarket”.

He has subsequently discovered that his first stop, the city’s ambulance centre, was intended for massacre – it was listed as a target on plans found in the possession of terrorists. There, he met the volunteers who took calls, drove ambulances, and treated the wounded on October 7, including former paratrooper commander Ophir Tor, 61. Before our interview, Rinder sends me some chilling CCTV footage posted on Instagram. A man in a T-shirt is seen swerving bullets. As he goes out of shot, three armed terrorists come into view. An unsuspecting minivan approaches. One of the terrorists stands in the road and points a rocket at the windscreen. And then an explosion. A group of elderly people, on their way to the Dead Sea, blown to smithereens. After narrowly missing those bullets, Ophir (the man in the T-shirt) tried to warn others to hide. He saved the life of a mother and son by ushering them away from the carnage and then helped others to the relative safety of the centre, before starting his shift. “He saw bodies in the road – children’s bodies, headless bodies – and described it ‘like watching a horror film’. And he remembered hearing the terrorists laughing. ‘They were enjoying it. They came only for death,’ he told me.

“Ophir immediately went into survival mode,” says Rinder, adding that something about his “quiet understanding” reminded him of his own grandfather.

In 1942, Morris’s mother, father and four sisters and brother were taken to Treblinka concentration camp, where they were murdered. Morris, then 19, was sent to forced labour in a glass factory before being sent to concentration camps, where he miraculously survived until liberation. He was one of 300 survivors known as the Windermere Children, brought over to the Lake District by the Jewish charity the Central British Fund.

Back in Sderot, Ophir retraced his steps with Rinder, “as if deconstructing a crime scene… a head blown off here, a rocket attack there. We ended up in the ambulance centre car park, where he listed the bodies of that day, scores of them: Holocaust survivors, children, young IDF soldiers,” adds Rinder. He had what Rinder describes as a “kindness of eyes... and was so stoic, so logical”.

After the army, Ophir decided to volunteer at MDA after his best friend and comrade had died in his arms.

“He became a paramedic to heal people because he couldn’t save his friend,” Rinder says.

From there, he travelled 45 miles to Kibbutz Magen, where a civil defence team managed to fight off terrorists, with only one member of the 350-strong kibbutz killed. They have all now been evacuated.

Driving south, Rinder passed the site of the Nova Festival – “a right turning up an innocuous road”.

“What we’re learning now is that many of those young people were engaged in activism for a peaceful two-state solution for Israel and Palestine.”

On Kibbutz Magen, Rinder met Shunit Dekel, 43, who had landed in Israel that morning and went straight to serve at MDA. She couldn’t get to her children, who were at home under attack. “She told me that the ambulances were being shot at and the volunteers going to save lives were being murdered, too.

“She told me how people who escaped the festival were ambushed by terrorists from every angle. Just as they’d thought they’d reached safety, they were shot dead. There was just no place to hide. If you drove north, you were shot. If you ran, you were shot. If you went to a shelter, you were shot.”

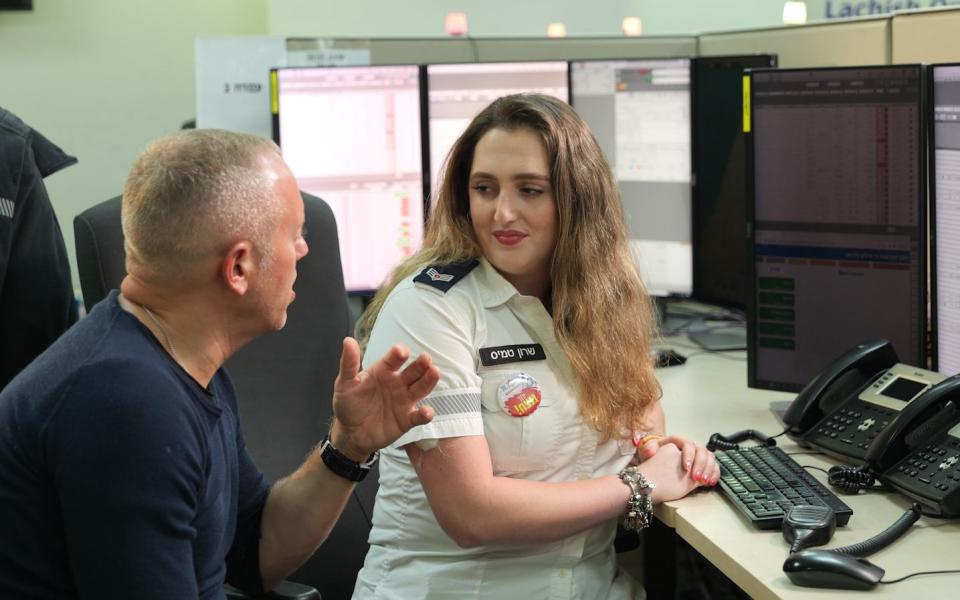

Another testimony he shares is that of Sharon Temis, 25, whom he met in the regional dispatch centre in Ashdod. She is a trainee doctor and also volunteers as an emergency dispatcher. On October 7, she was on the way to the airport for an overseas trip when she saw her phone’s red alert. She immediately turned her car round and went to the control centre. On a normal day there are a few “red calls”, for high-emergency situations.

On that morning, the screens of every dispatcher were entirely red. There were too many calls to answer.

Rinder says: “She described the screams of children, of men, of women, of grandmothers: ‘Save us’, Where are you?’, ‘Help us!’, ‘Please come now’. The ambulance tyres and doors were also being shot at. And the paramedics, too. Their radios started to go silent ‘making that soft sound the sea makes’.

“She spoke of a boy – Yotam, 12. He was whispering on the phone to her: ‘My parents and my brother and sister are dead.’ Sharon asked him where he was – he was hiding under a bed in his room. He could hear voices. She said to him: ‘I will stay with you, Yotam. You must be quiet for your Ima and Abba’ – for the sake of his mother and father. And she did. She answered other calls along the way, but she stayed with him on the call until he was rescued. He is the only survivor from his family.”

She does not know where he is now, says Rinder, but she “hopes he is with grandparents”.

Before Rinder leaves, Sharon’s colleague tells him that they also had to dispatch an ambulance to treat a terrorist that day. “I asked her why and she smiled – a real smile – and said: ‘Because we are for humanity. We save lives. Whatever kind.’”

For Rinder, it is that humanitarian spirit that draws him to MDA. The night before his trip, he posted an image on Instagram of him standing alongside members of the Jordanian Red Crescent (Jordan’s equivalent of the MDA).

In the caption, he highlighted that the Jordanians joined the International Committee of the Red Cross on the very same day as MDA [back in 2006] with a quote from Maya Angelou: “Hope and fear cannot occupy the same space”. The picture was taken on a charity bike ride a few years back – but represents so much more, a collaborative ethos Rinder feels is key in this age-old conflict.

“The starting point at the beginning of any mediation, before we can even come to a table, is to do the preliminary work of understanding that you and me share a common place on this earth as human beings,” he says. “And that’s where we start – with goodwill. For me, MDA and its volunteers are the best example of that goodwill, even against the backdrop of conflict.

“MDA also shares blood between Jews and Palestinians, and it’s impossible to think of a more, not just poetic, but profound and clear illustration of a shared humanity than sharing blood.”

MDA donor blood is used in Israeli hospitals for both Palestinian and Israeli patients and MDA exchanges blood with other members of the International Committee of the Red Cross if a rare blood type is needed. “Now that MDA is a member of the International Red Cross it is also sharing its advanced medical technology.” (The Jordanian Red Crescent team has recently visited Israel for that specific purpose.)

I ask Rinder how he felt as he headed home from his mission, but the seemingly simple question stumps him: “I don’t know. All I know is I wanted to capture on film these accounts of humanity and that’s what I did. And just like the other work I’ve done, if you walk away feeling touched by the stories you’ve captured, that’s always a good starting point.”

What touched him most? For that, he has a swift response: “The thing that always touches you most isn’t the horror, it isn’t the savagery, it’s always the good and the hope.”

Back in the UK, last weekend he was on the streets too, along with more than 100,000 others, to march against anti-Semitism.

This weekend Rinder plans to attend a vigil of humanity and hope with Israelis, Palestinians and all faiths, organised by Together for Humanity, which perfectly chimes with his ethos. Sadly, he feels the battle against anti-Semitism will be a “lifelong fight”.

“You can’t disinvent the hate,” he says. “You can only do what you can to educate children and empower them to stand against it.”

To find out more about the work of Magen David Adom UK and to donate, please visit www.mdauk.org