A Rochester astronomer thought he discovered Planet Vulcan during an eclipse. (He didn't).

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Even scientists can get overexcited during solar eclipses.

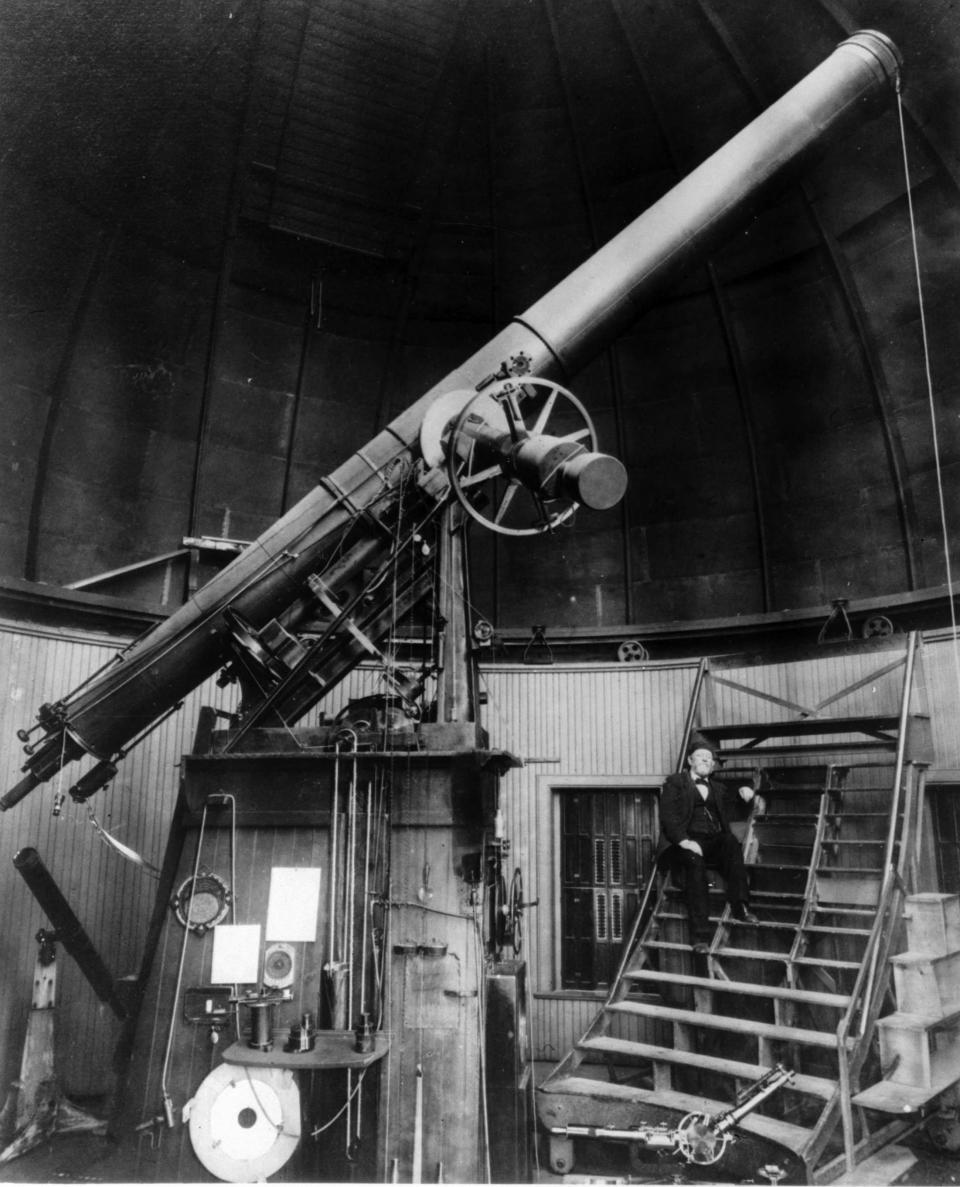

That's what happened to Lewis Swift, the famous Rochester astronomer of the late 19th century. He identified a dozen comets and more than 1,000 other space phenomena over the course of decades, many of them through a telescope mounted on the roof of a cider mill off State Street.

His reputation was gravely endangered, though, after he made worldwide news in 1878 for a fantastic proclamation: he claimed he had identified a small planet called Vulcan in between the sun and Mercury during a solar eclipse.

Almost immediately, skeptics pushed back on Swift and a better known peer who claimed the same thing. It took another 37 years before a still greater scientist, Albert Einstein, definitively proved them wrong.

Vulcan, we hardly knew ye.

What is Vulcan?

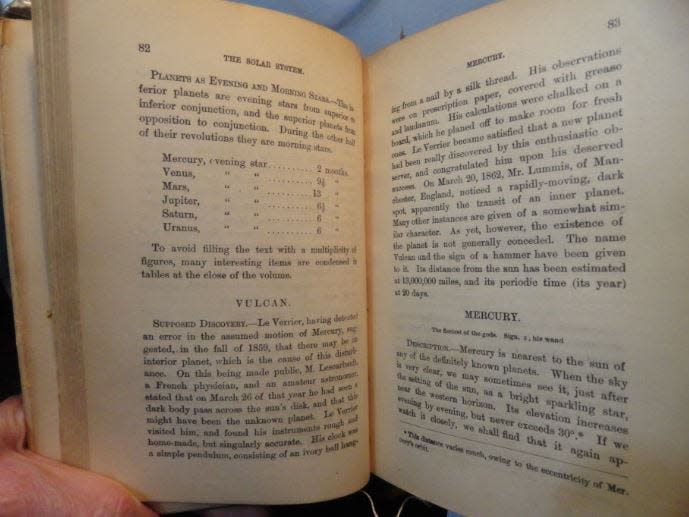

Vulcan had been tantalizing astronomers for decades by the time Swift set his telescope up the morning of July 28, 1878. Its intellectual provenance started with no less an authority than Sir Isaac Newton, who demonstrated in 1687 that the earthbound laws of gravity applied to celestial bodies as well.

That Newtonian principle led to an intriguing problem when it came to Mercury. Astronomers' calculations of the gravitational forces affecting Mercury's orbit didn't fully explain its irregular ellipsis. Something was pulling on it that they couldn't see, bending it ever so slightly farther than otherwise expected.

Whatever it was, it had to be big — possibly another planet altogether, named Vulcan in advance. And while the hypothesis seemed bold, there was a celebrated precedent.

French astronomer Urbain le Verrier had gained international acclaim by solving a similar riddle with Uranus' orbit in 1846. He figured out through math the size and location of the hypothetical planet that was pulling on Uranus and encouraged his peers to verify through direct observation. Lo and behold, there was Neptune, the last of the eight planets to be discovered.

Vulcan promised to be the ninth, with everlasting fame attaching to the astronomer who first observed it. But the search had one major challenge: browsing Mercury's orbit usually means staring directly into the sun. Only during a solar eclipse could telescopes safely scan for Vulcan.

The solar eclipse of 1878

Such were the stakes on the afternoon of July 29, 1878, when the moon slid in front of the sun in the western United States. Totality began at 3:13 p.m. and ended just less than three minutes later. Lewis Swift was on Capitol Hill in Denver with a team of scientists from the Chicago Astronomical Society.

"Almost at once my eye caught two red stars about 3° south-west of the sun, with large, round, and equally bright discs," Swift wrote later that year in a letter to the journal Nature. "I then carefully noted their distances from the sun and from each other ... and recorded them in my memory, where, to my mind's eye, they are still distinctly visible."

Swift was well known as a comet-finder but lacked formal scientific training — he ran a hardware store during the day — or any formal affiliation.

More: The last time Rochester was in the solar eclipse path of totality, clouds got in the way

In the national press, then, his observation was viewed mostly as supporting evidence for a claim made by a better credentialed astronomer, Ann Arbor Observatory Director James Watson, who had made his eclipse-watching camp in the ramshackle Western town of Rawlins, Wyoming. Watson was joined, among others, by Thomas Edison.

Watson and Swift were absolutely convinced of what they'd seen, but others were skeptical. Two people had seen Vulcan, supposedly — but what about the hundreds or thousands of other trained astronomers who were looking for the same thing in the same place at the same time, and saw nothing?

"Veterans of the Vulcan quest had heard this before," author Thomas Levenson wrote in "The Hunt for Vulcan," his book on the would-be planet. "One man gets to see it; everyone else doesn't. Again."

Watson and Swift engaged in heated combat in the pages of newspapers and scientific journals, rebutting claims that they'd misinterpreted their own observations. Swift in particular was indignant to be dismissed as an amateur, a barb that stung all the more because it technically was true.

“I wish most emphatically to say ... that I have not been the victim of a delusion, nor have I attempted to palm off upon the world a deception," he wrote in 1879. "Scarcely a clear night in twenty-two years has passed, that my telescope has not pointed to the sky, searching out the mysteries that lie within its grasp, yet not once has it deceived me, nor did it then.”

He conceded, though, that "many years, perhaps centuries may roll by" before the truth was known definitively.

Thirty-seven years, to be precise.

Astronomers in the 1800s believed there was one extra planet in the Solar System. Vulcan, the hypothetical planet, was meant to be between Mercury and the Sun. #FACT pic.twitter.com/Ew8IBKZ8nN

— The Fact Site (@TheFactSite) March 31, 2024

More by Justin Murphy: Superintendent Carmine Peluso calls leaving RCSD 'my next, best move'

Einstein kills Vulcan

Maybe Lewis Swift saw Vulcan in July 1878, or maybe he didn't. But the problem remained that Mercury's orbit deviated from what classical Newtonian physics predicted.

What could explain it?

Nothing less than a fresh theory of the universe, as it turned out.

By 1915, Albert Einstein had left a decade-long debris field through the foundations of 19th century physics. A speech and subsequent publication in November 1915 capped his general theory of relativity — with Vulcan and Mercury's orbit at the heart of it.

As Levenson summarizes: "The sun with its great mass creates its dent in space-time. Mercury, so firmly embraced by our star's gravitational field, lies deep within that solar gravity well."

The theory of gravity that governs apples falling from trees, in other words, cannot be applied in the solar suburbs.

Swift wasn't around for the denouement. He died in Cortland in 1913.

The false spotting of Vulcan, however, had not defined his career (neither had his confident assertion that a curveball in baseball is an optical illusion). Rather, he was remembered as a comet-spotter par excellence. He is credited with having been the first to see 13 comets plus about 1,200 nebulae.

One nickname was Comet Swift; another was The People's Astronomer. Local businessman H.H. Warner was inspired by his work and built him an observatory on East Avenue. It opened in 1882 with Swift serving as host and resident astronomer. It was the first major observatory in the world to open its doors to the public.

"What I have accomplished under discouraging difficulties has been the offspring of perseverance, the details of which I have written for the amateur to follow where unfathomable mysteries in the heavens still await him to solve," Swift wrote in a retirement essay in 1901. "(I am) only hoping that he can say as do I, that sometimes, 'Though bitter has been the bud, Yet sweet has been the flower.'"

— Justin Murphy is a veteran reporter at the Democrat and Chronicle and author of "Your Children Are Very Greatly in Danger: School Segregation in Rochester, New York." Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/CitizenMurphy or contact him at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: During a past solar eclipse, an astronomer said he discovered a planet