This Rochester veteran was one of few Black soldiers to see combat in World War II.

Last November, just before his 99th birthday, Thomas J. Bostick boarded a plane for New Orleans. He donned his signature blue bomber jacket and a baseball cap, both emblazoned with the logos of Buffalo Soldiers ― part of his legacy and the reason for his trip.

Bostick, who lived in Rochester most of his life, served in the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II ― one of two divisions comprised of all-Black soldiers during the height of segregation. The nickname “Buffalo Soldiers” stems back to the first regiment of Black soldiers formed in 1866 and was passed down through generations of their peers.

Bostick, like many Black soldiers, faced a grueling experience in the war, his daughters said, trudging through combat while also experiencing racism within the military that sometimes disparaged him more than the enemy he was sent to fight.

“He expected when he got out, because he had fought for his country, things would be different. His country would treat him better,” his daughter Sheila Clements said. “It bothered him tremendously when he came back home and still wasn’t recognized.”

Bostick died April 13 at 99, his family said. Funeral services took place Monday, April 24, at St. Monica’s Church on Genesee Street.

In an interview at their home, his three daughters said Bostick’s life was much more than that of a Buffalo Soldier. For all he endured, Bostick made sure to also live fully and freely on his own accord.

Last year, at 98, Bostick was likely one of few Black World War II veterans still alive, nearly eight decades since the war. The National World War II Museum estimates that of 16 million Americans who served in the war, just over 167,000 were still living in 2022. Black Americans made up about 1.2 million of that total.

So, when the museum invited Bostick on a Soaring Valor flight to visit the space in New Orleans last year, he went.

It was his way of making sure Black soldiers were represented and honored.

A Buffalo Soldier in the making

Bostick was born in North Carolina in December 1923 to farmers, the youngest of seven boys with one sister.

His first memory of the war was the attack on Pearl Harbor, a place he had never heard of.

Japanese forces attacked the Hawaiian naval base just before Bostick’s 18th birthday ― marking the United States’ (and soon his own) entry into the war in the Pacific. Bostick learned of the attack from a small radio in his brother’s bar. The local newspaper ran an extra “read all about it” edition, he said in an interview for the National World War II Museum’s archives.

He was drafted just over a year later in February 1943.

“It was kind of exciting being drafted because I never went anyplace of interest (before that),” Bostick said.

Most Black soldiers at the start of the war were relegated to non-combat roles, working supply, maintenance and transportation duties. But as the war dragged on and more troops were killed, the military began to introduce Black soldiers to combat.

Bostick was one of them, serving in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and the Philippines as staff sergeant of Company H, 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Infantry Division.

Still, Bostick said, his white peers never considered him their equal.

“We was Americans but we wasn’t Americans,” he said in the archival interview.

Segregation persisted in mess halls and bath areas. His daughters said Bostick described how Black soldiers were forced to wash their belongings downstream from where white soldiers and prisoners were washing. They had to pay for care packages that others received freely.

A Japanese radio broadcaster once questioned how Black soldiers could aid the same people who were mistreating them at home.

“We didn’t have no freedom,” Bostick said he remembered thinking at the time. “We were slaves. We just did what we were told to do and that was it. But we didn’t know any different. That was all we had ever seen.”

A turning point to that thinking came with the war’s end.

Bostick’s unit was in the Philippines preparing to invade Japan when U.S. forces dropped the atomic bombs that would end the war.

His return home was met with little fanfare. Black soldiers were not celebrated like their white counterparts. Bostick was locked out of benefits like home and education loans, his daughters said. When he sought treatment for jungle rot he contracted in service, he was turned away from army doctors because he was Black.

“I felt like I had paid my dues when I was gone, and I deserved what everybody else had,” Bostick said. “I was very, very angry back then because things hadn’t changed.”

From a soldier to a family man

But just over a year after his return home in 1946, Bostick shifted his focus.

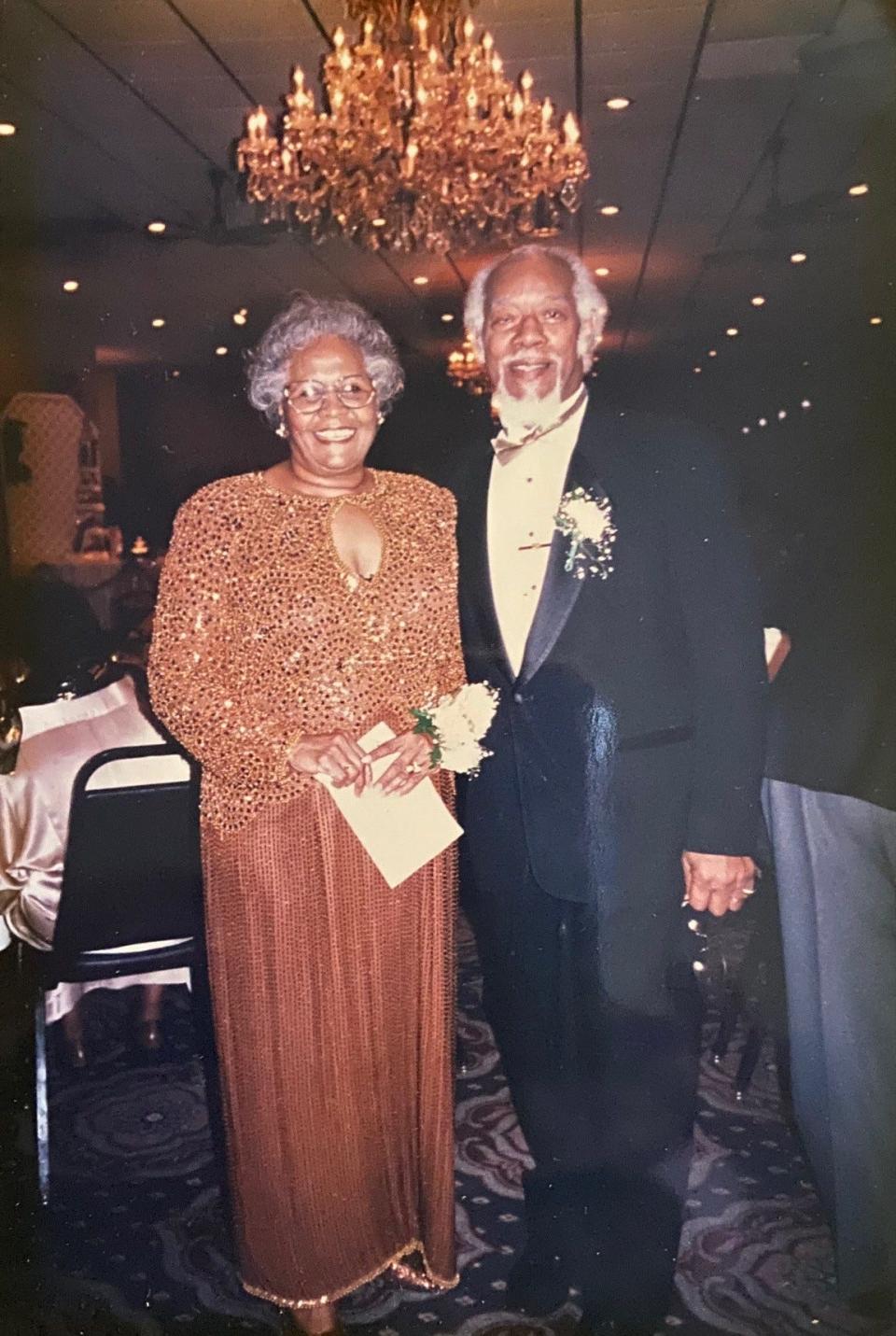

He met his wife, Nellie, in North Carolina, and the two married before moving to Rochester in 1947, where they had three daughters: Sheila Clements, Debra Graves and Victoria Butler.

Bostick worked for 36 years at Bausch and Lomb. Eventually the family settled in their long-time home in the city’s 19th Ward.

For some time Bostick served as the commander of the Pennington-Moye VFW Post 9251, once an all-Black post in Rochester, where he helped revive membership to ensure Black veterans would be recognized among others.

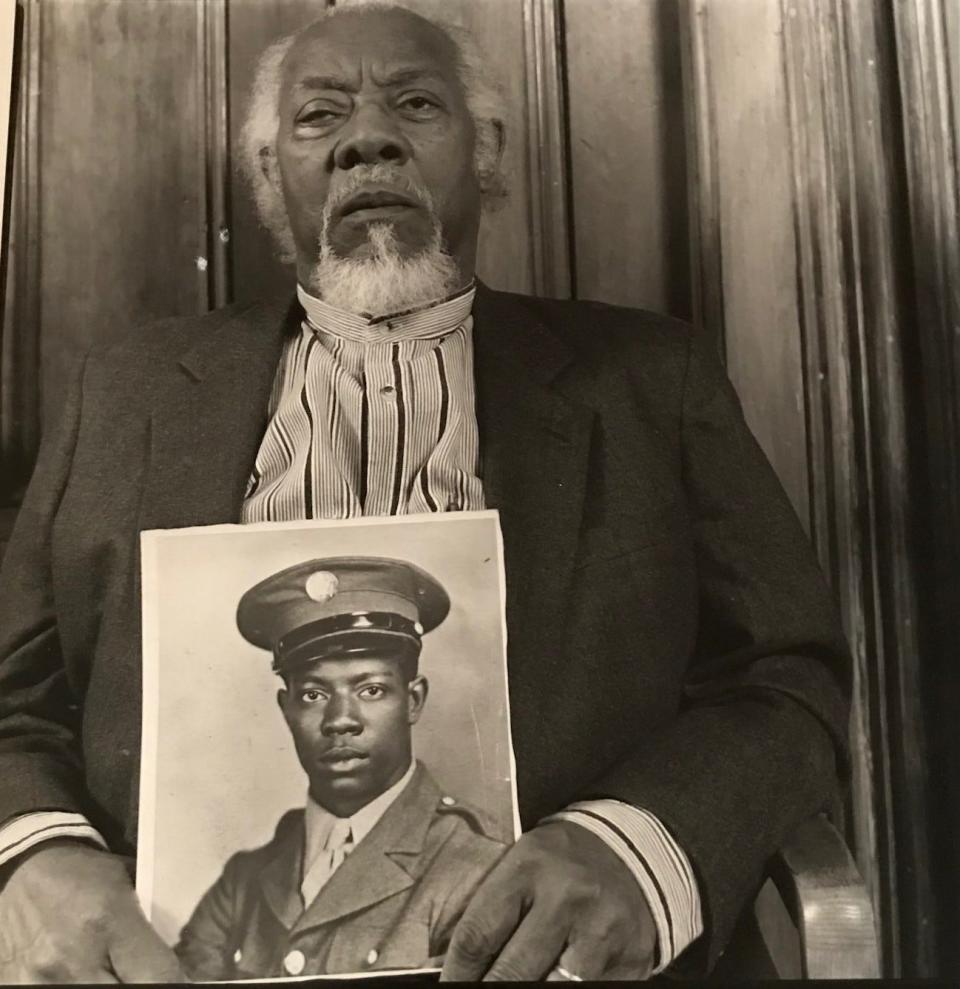

Even later in life, when Black veterans were more celebrated, Graves said her father faced skepticism from some who didn’t believe Black soldiers saw combat that long ago. She said her father made sure the post marched in every parade and wore his Buffalo Soldiers jacket to every doctor’s appointment to bring visibility to their history.

But for most of his life, Bostick was simply a man who loved his family.

Butler remembered her father as a "girl dad" who could braid their hair and would let them comb his.

Graves recalled the times he would dotingly fix them a hot lunch ― whatever they wanted ― on his days off work.

Clements said he had the answer to every question and a laugh that would make you cry.

They said where Bostick went, Nellie followed, and vice versa ― to the point that they changed their license plate to read “TJNELL” because they were always together. The pair traveled to well over a dozen Super Bowl games ― without tickets ― instead basking in the tailgate parties as one of their many adventures.

After his retirement, the couple took a great-granddaughter into their care. Bostick made sure to take the child on a daily walk at 12:30 p.m. sharp to make room for Nellie to watch “The Young and the Restless," according to his family.

When Butler’s son was deployed to Iraq, he and Bostick developed a special bond, calling each other “sarge” from thereon out.

When Graves’ son died unexpectedly in 2021, Bostick was her rock.

“He made it OK to go on,” she said.

The family grew to include so many that the three sisters must name them all aloud to keep count: Six grandchildren, 15 great-grandchildren and seven great-great-grandchildren.

And on holidays, Bostick would gather them all, sit back and turn to Nellie with a smile, saying, “This is us. We did this.” His legacy.

“If you knew him, you loved him,” Graves said. “He was our life.”

His parting words, his daughters said, were always: “I love you. Be good to yourself.”

And that, not his military valor, is what sticks with his family most now that he’s gone.

Kayla Canne reports on community justice and safety efforts for the Democrat and Chronicle. Get in touch at kcanne@gannett.com or on Twitter @kaylacanne.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Remembering Thomas Bostick, a Black WWII veteran who served his family