Roe vs. Wade is doomed. A veteran feminist thinks other rights are at risk

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ever since the Supreme Court’s draft opinion overturning Roe vs. Wade was leaked, Barbara Smith has felt as if she were living in a time warp.

After all of the fights waged and victories won to secure federal protections for women, Black Americans, and gays, lesbians and transgender people, she says, the nation seems to be hurtling back to the repressive days of “Father Knows Best,” when gender equality seemed like a fantasy, LGBTQ people faced routine harassment by police, and the concept of “separate but equal” was still widely embraced.

An author and publisher who’s earned accolades for her lifetime of work as a Black feminist, LGBTQ activist and advocate for legal and safe abortions, Smith takes this new blow to women’s rights personally.

“Once Roe falls, it’ll be open season on all of those other rights that are not written in the Constitution — it’s the domino theory,” says Smith, 75, speaking by phone from her home in upstate New York.

“They’re trying to erase the work of a whole generation,” she says. “My generation.”

I reached out to Smith, among other LGBTQ experts, because I wanted to know what it was like for those who are involved in overlapping civil rights struggles to bear witness to the court’s anticipated decision on abortion — and because I suspect, as they do, that Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s draft opinion striking down Roe vs. Wade is part of a larger effort to reverse 60 years of social progress on multiple fronts.

Smith and millions of Americans, myself included, are left to wonder: Will some aspect of our lives make us the targets of the next big court challenge?

Though Smith was feeling drained from a recent knee surgery, she spoke with a booming voice during a lengthy phone conversation on the implications of the justices’ expected ruling to strike down the 1973 decision that legalized abortion nationwide.

The court’s action feels like a threat to everything Smith represents as a person, especially when leaders like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) back up those fears by voicing their own concerns that same-sex marriage and other civil liberties also might fall.

“I wouldn’t put anything past them,” Smith says of the court’s conservative majority and its supporters in Congress and in statehouses across the country. “Gay marriage, they’re coming after that.... I wouldn’t be surprised if they come after civil rights for people of color, too.”

A Black American who grew up in Cleveland, Smith is old enough to remember the humiliation of racism before the Supreme Court struck down school segregation in 1954. And she was just finishing high school and on her way to college when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts a decade later.

As a lesbian, Smith knows firsthand the pain that comes with being viewed by some of her fellow citizens as a pariah because of whom she loves.

Her voice briefly trembles when she recalls having to comfort a distraught graduate school classmate in the late 1960s who terminated two pregnancies at a time when there was a profound stigma attached to seeking an abortion.

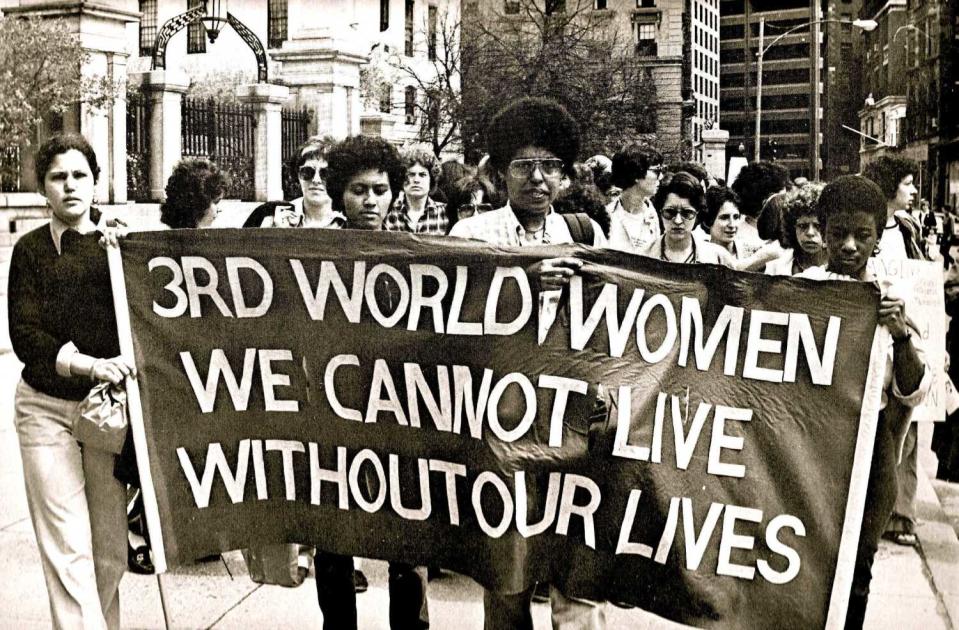

Smith was part of a collective of Black lesbian activists and thinkers in the 1970s who introduced the concept of “identity politics” to describe the intersection of race, gender and sexual orientation in discussions about the injustices they faced in a society designed to benefit white, heterosexual men.

She founded Kitchen Table Press at the urging of her friend and fellow writer Audre Lorde, to showcase the experiences, history and wisdom of Black and brown women, in part because their stories and struggles were often missing, even within the broader racial justice, feminist and queer rights movements.

“When Vice President Harris says women have been doing this kind of work for a long time, I’m like, ‘Tell me about it!’” Smith says.

Forty years after Smith edited seminal collections like “Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology,” some Americans dismiss terms like “feminism” and “identity politics” as merely obsessions of the far left. But Smith’s raw insights resonate with me as I try to understand why the abortion ruling feels so ominous.

“It’s like death by a thousand cuts,” says Jennifer Gregg, executive director of the foundation that supports ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries in Los Angeles, one of the largest repositories in the world of documents, photos and other materials related to the LGBTQ community.

Gregg, 49, who is white and lesbian, believes as Smith and I do that conservatives want to chip away at civil liberties broadly, not just on the issue of reproductive health.

She keeps a copy of a photo from the archives on her wall at home that shows protesters in L.A.’s Silver Lake neighborhood demonstrating against police raids at gay and lesbian establishments in 1967, two years before the Stonewall uprising in New York City launched the modern gay rights movement nationally.

One of the protesters holds a sign that reads, “No more abuse of our rights and dignity.”

Smith finds it hard to accept that the justices could so boldly endanger the individual rights and basic dignity of Americans from different walks of life with a single majority opinion.

When she was coming of age, women of color had an especially difficult time securing reproductive services and healthcare in general because of inequality in the medical system. Those hardships still exist.

Black and Hispanic women represent a disproportionate share of those who terminate pregnancies in the U.S. Many of those women live in states like Texas, Louisiana and Alabama, where Republican lawmakers over the years have placed onerous restrictions on abortion services, essentially making them impossible for many women to find without traveling great distances.

And Black women who do choose to carry their pregnancies to term face higher rates of maternal and infant mortality than white women due to racial and economic disparities in healthcare and in society as a whole — an issue that has never been fully addressed.

Smith was addressing these inequities in her writings, in classrooms and on the streets when Kamala Harris, the first woman and Black person to become vice president, was still in grade school in the Bay Area.

Smith’s tone softens with nostalgia as she reminisces about joining a coalition of women from different backgrounds to hand out health literature containing information about abortion services to residents in Boston’s predominantly Black Roxbury neighborhood.

“That took so much guts — this was the mid-’70s,” Smith says. “Here we were, these young women of color — there were Latinas, a young Asian American woman — on both levels of the station handing out pamphlets.”

Thinking back on her career, Smith sounds proud of all she’s done to bring about a more inclusive and understanding society, and unnerved by efforts that erode that spirit of compassion.

The pushback against acceptance of LGBTQ Americans, which strikes special fear in Smith, has been building for years but feels more dire with the court’s impending ruling, says attorney Sharon McGowan, chief strategist and legal director at Lambda Legal, one of the nation’s largest LGBTQ civil rights organizations.

“When people talk about LGBTQ rights being ‘next,’ well, ‘next’ is now,” says McGowan, 48. “Justice Alito has been saying all of the things that his draft opinion on Roe v. Wade is saying from the mountaintops every chance he gets. His view is that unless you are someone who has always exercised their full rights and liberties under the law, you’re out of luck. This is the beginning of a wake-up call for many who didn’t believe the threat was real.”

While Smith is shaken by the court’s ruling, she isn’t necessarily surprised that Americans are so divided. After all, while 81% of Democrats support having lawmakers in Washington pass legislation to make abortion a right nationwide, only 65% of independents and 30% of Republicans feel the same way, according to a new CNN poll conducted by the research firm SSRS. Voters remain so entrenched that so far, the court’s draft ruling doesn’t seem to have shifted the dynamics of a midterm election battle in which Republicans stand to make major gains in Congress.

At the same time, Republican leaders like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott have attempted to score points with their supporters by backing bigoted education measures that stoke resentment toward LGBTQ people, immigrants and Black Americans.

No one should live under the illusion that the fight for equality, mutual respect and the right to privacy ended in the ’60s and ’70s, says Smith, who now spends her time editing manuscripts and serving as a senior advisor to the Women’s March coalition that arose in response to the election of President Trump in 2016.

As I listen to Smith talk about the nation’s civil rights triumphs and setbacks through her personal lens, it’s clear that she and her cohorts in the ’70s had it right: Acknowledging the role that identity plays in our politics is key to understanding the nation’s fault lines.

What kind of person makes a good American? Who is worthy of enjoying the nation’s rights and freedoms? And who should have the power to decide?

After 246 years, a Civil War over slavery, movements against inequality and injustice, and a blossoming of social consciousness ushered forth by people like Smith, Americans are no closer to agreeing on the answers.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.