This is the role NJ played in ending segregation in the US armed forces | Stile

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the New Jersey National Guard actively recruited soldiers in a post-World War II overhaul, the U.S. Army bluntly reminded units in Newark that the new Guard would operate under the old rules of racism.

“Under the present Department of Army policy, Negroes cannot be enlisted in white units," read an order issued Jan. 28, 1948.

New Jersey Gov. Alfred E. Driscoll had other ideas.

Five days later, the Republican reformer bluntly notified Maj. Gen. Clifford Powell, the New Jersey Guard commander, to ignore the Army order.

And by mid-February, the state’s adjutant general took it one step further, issuing General Order No. 4, which explicitly forbade segregation in New Jersey Guard units.

African American leaders and civil rights advocates around the country, who feared that Driscoll was wobbling in his commitment to equality — the year before, Driscoll guided passage of a progressive new state constitution prohibiting segregation in schools and the state Guard — now cheered him as their bold new champion.

As President Harry Truman dragged his feet on a promised civil rights agenda, the lanky Driscoll, who traced his lineage back to the men who fought in the Revolutionary War, charged ahead.

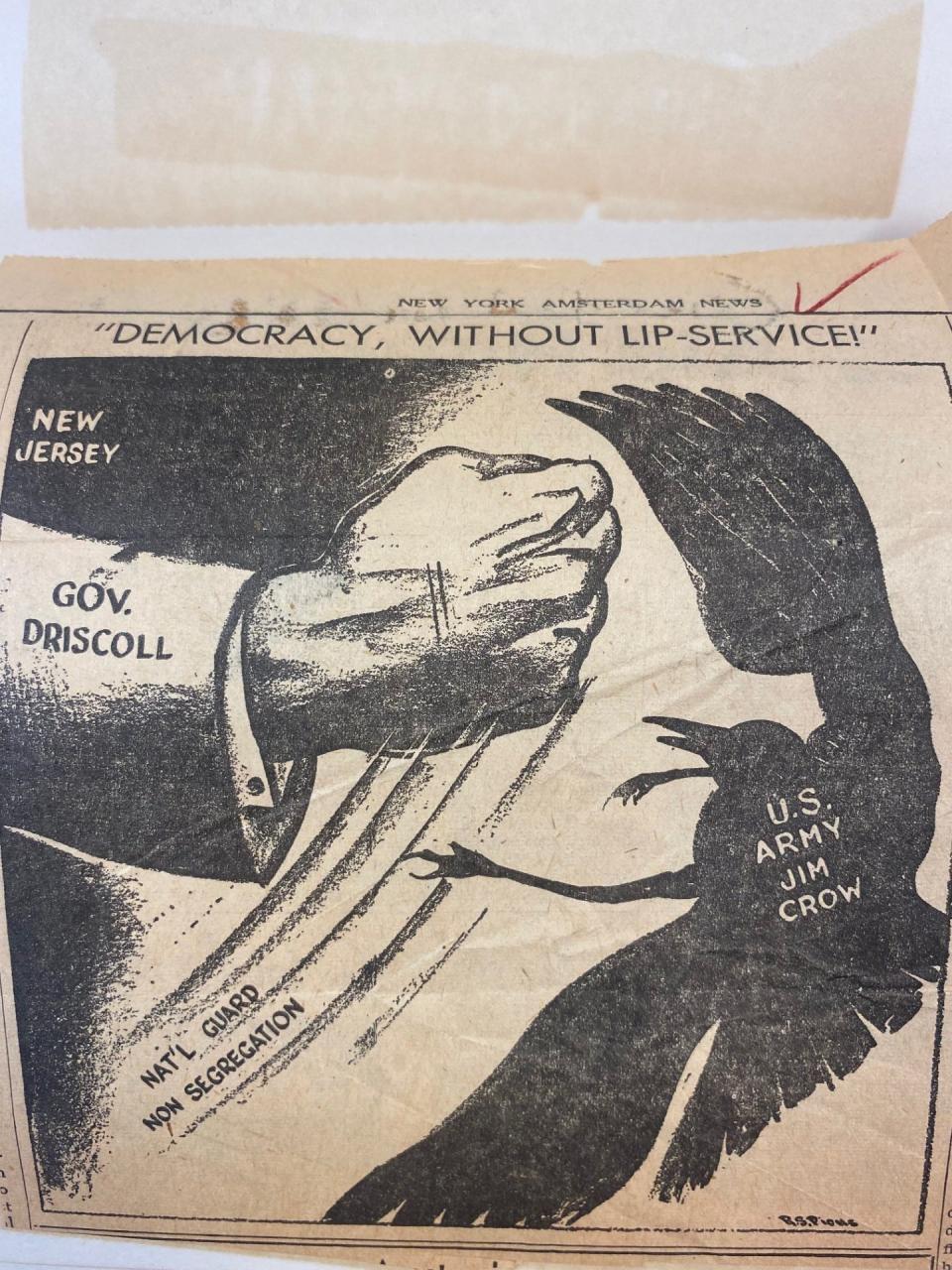

“Governor Driscoll smashes War Department Jim Crow Ban,” announced the New Jersey Herald News, “New Jersey's Oldest Colored Weekly.” A political cartoon in the New York Amsterdam-News depicted Driscoll’s fist delivering an uppercut to a “U.S. Army Jim Crow.”

“Democracy, without lip service," read the cartoon's caption.

And in the months that followed, Driscoll’s action inspired other states to take steps to desegregate their National Guard units.

Overshadowed by Truman

Driscoll’s disobedience, outlined in faded mimeographs and brittle copies of old telegrams filed in the New Jersey State Archives, is a forgotten episode in New Jersey history, overshadowed by Truman’s executive order on July 26, 1948, to formally end segregation in the U.S. armed forces.

Historians and activists will undoubtedly reflect on the importance and implications of Truman’s order, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this week. But New Jersey was the first state to take such a leap, beating Truman to the starting gate by six months.

And while a wide range of political and social forces eventually prompted Truman’s decision — not the least of which were Black veterans demanding the full privileges of democracy that they risked their lives fighting for in World War II — Driscoll’s rebuff increased the general pressure on Truman to act.

“New Jersey’s actions put the state decisively ahead of the federal government in eliminating discrimination within the military," Joseph G. Bilby wrote in his book “New Jersey: A Military History.”

Driscoll’s bold action also stands in stark, ironic contrast to the current governor, Phil Murphy, a progressive Democrat whose administration has actively fought a lawsuit seeking to desegregate New Jersey’s public schools.

Advocates, who began the effort five years ago, argue that New Jersey's racially polarized alignment of public schools violates the state constitution — the document that Driscoll helped shepherd to passage in 1947. The following year, it became the instrument he used to challenge the U.S. military’s racist legacy.

More from Charlie Stile: Against all odds, this Black NJ lawyer helped ignite the civil rights movement

How Driscoll's order came to be

Driscoll didn’t start out seeking to defy Truman’s Defense Department. He was seeking its guidance.

In the final weeks of 1947, Driscoll alerted Secretary of Defense James Forrestal that as of Jan. 1, he was obligated to enforce New Jersey’s new constitution, which contained the first-in-the-nation clause banning segregation in public schools and the state’s National Guard.

Driscoll was concerned that the New Jersey National Guard was at risk of losing funding and recognition once it began mixing Black and white soldiers, as the new state constitution required. Forrestal handed off the task of replying to Kenneth Royall, the U.S. secretary of the Army.

Royall, reflecting the Army’s institutional opposition to mixing the races, provided little clarity when he wrote to Driscoll on Jan. 13, 1948. While noting that management of the Guard was the state’s responsibility, the unit was “governed” by Army policy — including segregation. In some quarters, the reply was read as a complete dismissal of Driscoll's inquiry.

Meanwhile, in a related matter, the state Guard’s 50th Armored Division, based in Newark, was undergoing a postwar rebuilding process, which included the active recruitment of new soldiers.

Civil rights groups in North Jersey watched the developments warily, fearing that the state Guard would restock the division with segregated units before the new constitution went into effect on Jan. 1. They lobbied Driscoll to prevent the imposition of “Jim Crow” units in Newark and Jersey City.

It was this simmering recruitment controversy that prompted the War Department in January to issue its decree in Newark reaffirming the policy of segregation. That announcement, coupled with Driscoll’s failure to get a clear, decisive answer from Royall or Forrestal and their subordinates, apparently pushed him to the breaking point.

And on Feb. 4, 1948, he issued his terse memo to Powell, the Guard commander.

“All state agencies and departments are required to observe the letter and spirit of the constitution," Driscoll wrote.

News of Driscoll’s decision garnered headlines in The New York Times — and caught the attention of Marx Leva, Forrestal’s assistant. Leva was aware of the turbulent domestic political environment on race and the political implications of New Jersey’s actions.

At the same time, the commander in chief was walking a political tightrope. Aware of the postwar pressure to expand civil rights, Truman empaneled a special committee that condemned segregation in the armed forces and labeled the “separate but equal” rationale undergirding segregation “a myth.”

More from Charlie Stile: Who was Oliver Randolph, New Jersey's civil rights pioneer?

And he also delivered a historic special message on civil rights to Congress on Feb. 2, 1948, announcing that he had ordered Forrestal to take steps “to have the remaining instances of discrimination in the armed services eliminated as soon as possible.”

Yet in the first half of 1948, Truman failed to follow through, concerned that southern segregationists would bolt the Democratic Party and destroy his reelection chances. But Truman was also facing pressure on his left flank from civil rights activists, including labor leader and activist A. Philip Randolph, who was urging young Black men not to register for the draft unless the armed forces were desegregated.

It was in this context that Leva urged Forrestal to have a talk with Royall about the New Jersey controversy.

“This is a serious matter both from the standpoint of practical considerations and the standpoint of political implications,’’ he wrote.

At Forrestal’s prodding, Royall wrote again to Driscoll on Feb. 7, extending to New Jersey what amounted to an exemption from federal policy. He asserted that even though the U.S. Army policy required segregation of troops, he recognized the importance of a sovereign state adhering to its constitution.

That gave Driscoll the green light he had been seeking. Several days later, New Jersey issued its General Order No. 4, banning segregation in the state Guard. And in early March, Driscoll obtained a similar exemption for the New Jersey Air National Guard.

A chain reaction set in motion

Telegraphs poured into Driscoll’s office in Trenton praising his action. The Department of Defense’s partial retreat also sent off a chain reaction in other states, according to “Desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces: Fighting on Two Fronts 1939-1953," by Richard Dalfiume.

Connecticut’s governor wrote to Truman, complaining that his state had been trying to integrate its units for a year, only to be warned that it would lose federal recognition and support.

New York’s Legislature empaneled a special committee to investigate integration, a move endorsed by Gov. Thomas E. Dewey, Truman’s opponent in the fall race for president. The governor of Minnesota also wrote that he wanted to integrate his state’s Guard by executive order.

The issue would roil Truman over the next few months as his administration vacillated, with liberal White House aides pressing for more aggressive action while military leaders opposed change.

It was not until the Democratic Party liberals were inspired by Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey’s civil rights rallying cry at the party convention in July that the matter came to a head.

In a historic floor vote, the convention voted 651½ to 582½ on July 14 in favor of a civil rights plank in the party platform that included a call to desegregate the military. Southern delegates walked off the floor in protest and would later form the “States' Rights Democratic Party,’’ or the “Dixiecrats.”

The convention made clear to Truman aides that his reelection in the coming campaign now depended on a large turnout of Black voters in the Northeast and swing states. He was no longer walking the political balance beam worried about the southern states.

Twelve days later, he issued his desegregation order.

But in some ways, it was a significant milestone for Driscoll, who a year earlier earned praise and recognition for enactment of a modernized constitution, which led the nation with its progressive ban on segregation in the classroom and the Guard units.

The provision ensuring equal access to the classroom regardless of race came seven years before the U.S. Supreme Court issued the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling, ending segregation of public schools.

But in 1948, the constitution became a club in Driscoll’s hand, and he pressed ahead to integrate the state National Guard. And it came months before Harry Truman chose to act.

Charlie Stile is a veteran New Jersey political columnist. For unlimited access to his unique insights into New Jersey’s political power structure and his powerful watchdog work, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: stile@northjersey.com

Twitter: @politicalstile

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: History of how NJ helped end segregation in US military