From Rolfe Neill I learned lessons that stuck a lifetime

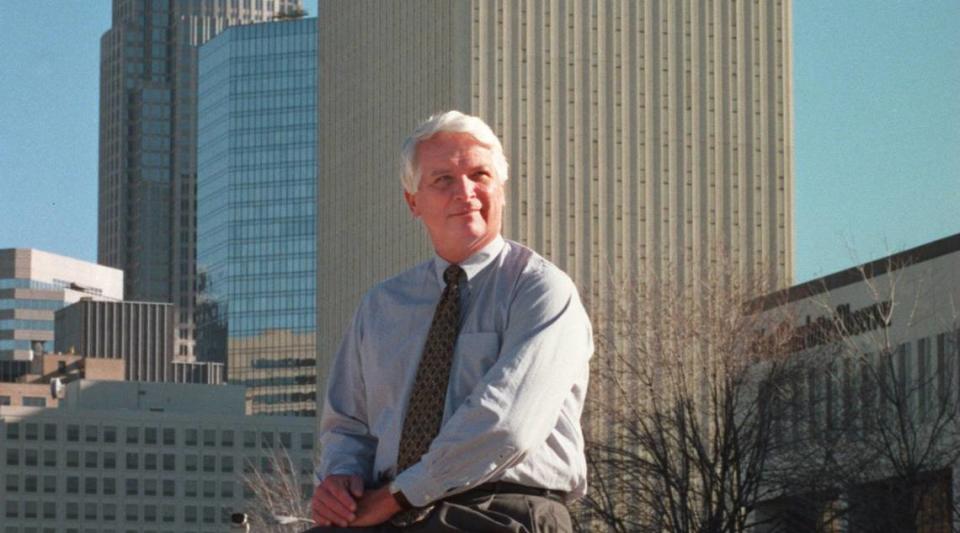

No person in the history of The Charlotte Observer had more impact on the quality and growth of the newspaper than Rolfe Neill, who died early Friday. His influence on the city of Charlotte was matched by a handful of people, some of whom worked alongside him in building institutions of arts and humanities.

He was the most brilliant editor I ever worked for. I use the editor’s title deliberately, even though he was never the Observer’s editor. He was the publisher, with a fine executive’s instincts, but he was a consummate editor demanding the best in his journalists and the pages they produced. He acted with energy and resolve. Others will tell of his impact on Charlotte. I knew him as an editor.

I often was called to Rolfe’s office. He sat across from me, legs stretched over an ottoman, shoes off, fingers tented on his chest, brow furrowed, a can of Coke beside him, asking how I came to a decision to publish (or miss covering) a certain news story, with the pursuit of a seasoned prosecutor, his questions gradually leading me to see the errors of my way. We did not always agree, but I usually left exhausted and determined to do better the next time. I learned lessons that stuck a lifetime.

About that Coke. Rolfe did not drink alcohol. In an exceptional Business North Carolina profile of Rolfe written by former Observer editor Rick Thames, Rolfe said, “My drink of choice is industrial strength Coca-Cola.” He had a refrigerator in his office packed with Cokes. He disliked New Coke, and hoarded cases of the traditional Coke, offering cans to visitors as precious gifts.

In the early 1980s, we published a short article reporting the arrest of several dozen men for alleged sex crimes one night in a city park. We included their names. One of the men killed himself and now, a week later, his angry and grieving widow sat across from me in Rolfe’s office. To tell her that we had the “right” to publish names of arrested persons would be insensitive and hollow. I apologized, and learned a lesson never forgotten. The right to publish isn’t a requirement to publish. The alleged crimes were barely newsworthy, but life is precious. Through the meeting, Rolfe sat quietly. He had yanked me from the isolation of the newsroom to confront the consequences of a decision. Rolfe knew that some lessons teach themselves.

In its 136-year history, the Observer has won five Pulitzer prizes — three for editorial cartoons, two in 1981 and 1988 for Meritorious Public Service, widely considered journalism’s highest award. Those two public service Pulitzers came during the 15 years that Rolfe and I worked together.

My most searing experience with Rolfe involved the lead-up to the 1988 Pulitzer public service award to The Observer for revealing the corrupt practices of Jim Bakker’s PTL television ministry, a story of adultery, payoffs, tax fraud and abuse of regulated public air waves. Jim Bakker served five years in federal prison and PTL collapsed. We had invested 11 years of reporting.

In May 1986, Rolfe sent me a formal, signed note, something he had never done before, and a signal of impending disciplinary action. He warned me to “end your ceaseless thrall” with PTL. He believed our coverage was out of proportion to its importance. I disagreed. At the time, reporter Charles Shepard was close to documenting that Jim Bakker had paid $363,700, an amount later verified by the Internal Revenue Service, in silence money to Jessica Hahn, a Long Island, N.Y., church secretary. Hahn was threatening to go public with an accusation that Bakker had raped her in a Clearwater, Fla. hotel room.

We backed off the story and our tough editorials by Ed Williams, to the dismay of sub-editors. When we soon had authoritative proof that the silence money had been paid to Hahn, I went to Rolfe. He now was convinced we had a story and could carefully continue our work. Bakker sensed we were getting close and used his vast TV network to lead a subscription boycott of Knight Ridder papers, with the impact felt from The Miami Herald to The Mercury-News in San Jose, Calif. Now, convinced of our fairness to the facts, Rolfe stood firmly behind his editors and reporters.

As he told former Observer editor Rick Thames, “We were not afraid to be caught loving our community. On the other hand, we were never intimidated about addressing the community on sensitive topics that we felt needed talking about or taking a stand.” On the PTL story and so many others, Rolfe made us better.

David Lawrence, who retired as publisher of The Miami Herald, worked for Rolfe at the Philadelphia Daily News and as my predecessor as editor of The Charlotte Observer in 1975-78. “He had the quickest, toughest mind of a boss I ever had,” Lawrence recalled. “Diligent on details. Cared about the details as well as the big picture. Insisted on excellence in small things and big.”

Rolfe revealed his beliefs in newspapers in a 1991 column observing the death of James L. Knight. Jim Knight and his brother John S. Knight were co-founders of Knight Newspapers. Rolfe wrote that the Knights “agreed that good newspapers are made of political independence, fiscal stability, talented staffs, fair play, accurate reporting and absolute separation of advertising pressure from the news and editorial department.”

He was a man of compassion, but never showy. For a time when he was single, Rolfe lived in a garage apartment behind our house on Malvern Road. One evening he appeared at our back door and asked my wife Carol, “Do you have a washer?” Well, yeah. He was carrying the bedclothes of C.A. “Pete” McKnight, editor of The Observer during the Civil Rights era, who had suffered strokes and was in a nursing home. McKnight had hired Rolfe in 1957 to open the Gastonia bureau, later naming him business editor.

Rolfe’s humor ranged from Bob Newhart’s gentleness in public settings, to the incisiveness of Stephen Colbert in private, but it always was insightful. Retired book editor Dannye Romine recalls:

“It was after 6 o’clock, and I was heading down the Observer escalator, feeling bedraggled and hauling a load of review books to look at overnight. Rolfe was standing on the first floor, cooly watching me descend. When I reached the bottom, he said, “You look like someone who would’ve played the rhythm sticks in first grade!” Bingo! How did he reach into my psyche and find that scrawny little girl, left-handed and shy, who indeed played the rhythm sticks and longed all first grade to play the triangle. And that’s exactly how I felt that evening. Not that I liked what he said. But I was awestruck at his accuracy.”

Retired editorial page editor Ed Williams cites a quote from philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Every great institution is the lengthened shadow of a single man. His character determines the character of the organization.”

For Ed and me, and probably thousands of others in Charlotte and beyond, that perfectly defines Rolfe Neill.

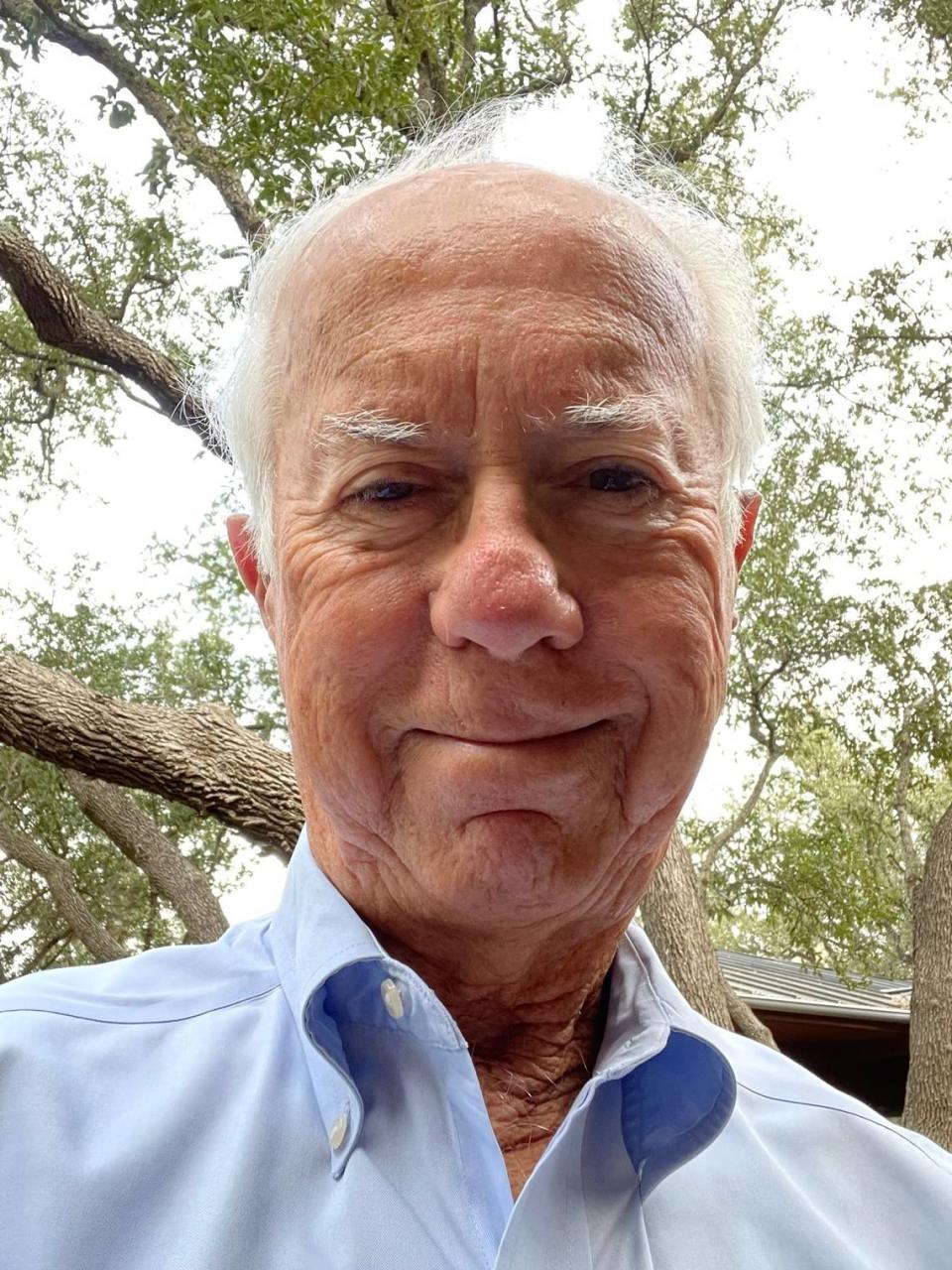

Rich Oppel, former editor and vice president of The Charlotte Observer, left in 1993 to become Knight Ridder’s Washington bureau chief. He later was editor of the Austin American-Statesman in 1995-2008, editor-in-chief of Texas Monthly magazine and vice president for media of Hill & Knowlton Strategies. He is retired and lives with his wife Carol in Austin.