‘Like a roller coaster’: DACA opens doors for two Texas brothers, leaves another in shadows

LAKE DALLAS, Texas – On a Monday morning in this Dallas suburb, the Medina brothers readied for work.

Leo Medina, 24, enjoyed a leisurely breakfast with his mom and grandparents and then drove to Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Dallas, where he earns $22 an hour sterilizing surgical equipment.

Isai Medina, 23, powered up laptops in the bedroom of his air-conditioned home, where he works remotely troubleshooting IT issues for a dental company.

By midmorning, however, sweat dripped from the forehead of the youngest brother, Carlos Medina, 20. He was laying down planks of laminate on the floor of an unair-conditioned trailer with their father, Darío Medina, one of the few jobs the two immigrants living in the U.S. illegally could find. As temperatures climbed into triple digits outside, the men hammered one plank after another, sweat spreading in a dark ring around the collar of Carlos Medina’s T-shirt.

Three hours later, father and son went on to their next job, unloading 100 60-pound square bales of hay at a client’s ranch. The work made their shoulders ache and left their T-shirts stained with sweat. Carlos Medina earned $16 an hour.

The Medina brothers came to the United States from Mexico with their parents at a young age. A key difference between them: Leo and Isai Medina were accepted into the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program.

Carlos Medina was not.

“It’s frustrating,” Carlos Medina said as he steadied another plank for his dad. “I don’t mind working with my hands. But I can’t see myself doing construction the rest of my life.”

As DACA turns 10 this week, the program boasts nearly 650,000 recipients and has paved paths to college degrees and better jobs for thousands of youths. DACA allows qualifying children of immigrants who were brought to the United States illegally protection from deportation, access to driver’s licenses and permission to legally work.

But as the policy has come under legal challenges in recent years, thousands of DACA-eligible youths have been left out. In 2017, former President Donald Trump rescinded the policy, which was later reinstated after the U.S. Supreme Court intervened. Last year, in a separate lawsuit attacking the policy, a federal judge in Texas ruled DACA was illegal and ordered a freeze on all new applicants while the policy’s merits are decided in court. The decision, which was appealed, put more than 80,000 first-time DACA applicants in a holding pattern, Carlos Medina among them.

Today, thousands of immigrant families navigate a life where one sibling reaps the benefits of DACA, while another can’t legally drive or work. Across the nation, 1.5 million people live with a DACA recipient, according to the Center for American Progress.

“It creates a lot of stress and heartache for the family members,” said Lindsey Harris, a Houston-based immigration attorney who works with DACA-eligible youth. Harris said she’s seen a rise in mixed-status families since the program has been challenged in court.

“It seems inherently unfair when you have two siblings with near identical immigration histories and one qualifies for a benefit like DACA and the other one doesn't,” she said.

‘Half an American dream’: DACA was meant to be temporary. 10 years later, immigrants want relief.

‘I don’t know if I will be deported’: Young immigrants prepare for DACA to end

‘Fear you carry each day’

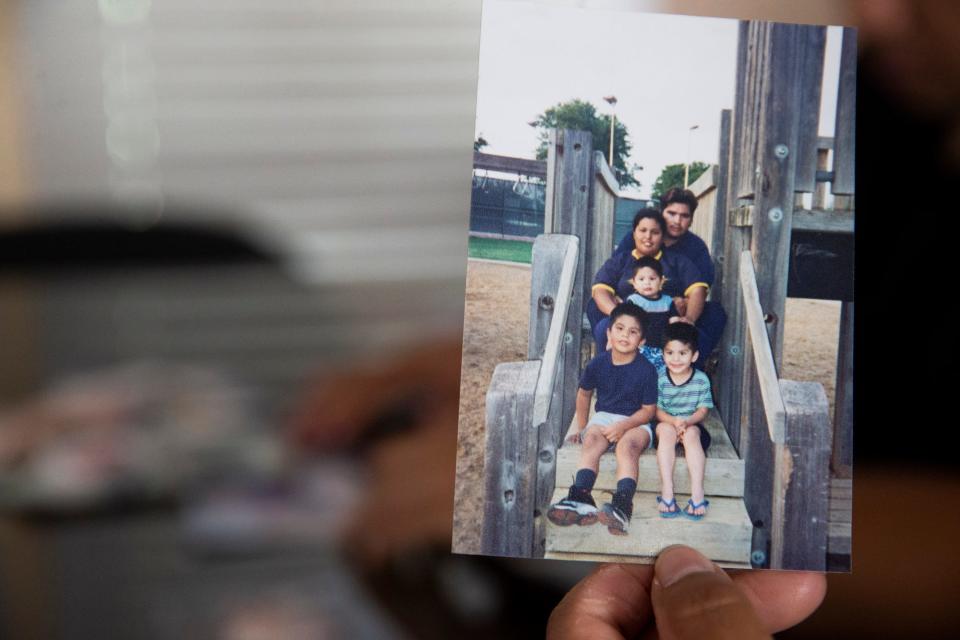

In 2002, Darío Medina and his wife, Janneth Gonzalez, fled the poverty and struggle of their home state of Coahuila, Mexico, and relocated the family to the United States. At the time, Leo was 4, Isai was 3 and Carlos was 6 months old. They arrived in Lewisville, near Dallas, on a tourist visa, initially staying with relatives, and then overstayed the visa.

Darío Medina worked first as a cook at McDonald’s and then for a company that cleaned Home Depots. Gonzalez worked the front register at a McDonald’s. The couple would alternate shifts so someone would always be home with the children.

Darío Medina insisted the family learn English. Recovering a TV and VCR that had been tossed in a dumpster, he played popular movies like "The Bodyguard" with Kevin Costner and “Lord of the Rings,” first with Spanish subtitles and then without them, over and over, until the English began to stick.

Leo and Isai Medina did well in school, shifting easily between English with teachers and friends and Spanish at home with their parents. Leo mowed lawns in the neighborhood for $25 each, while his parents moved from one menial job to the next. The family lived paycheck to paycheck, scrambling to make the $650 monthly rent and buy groceries. It was not uncommon for the electricity or water to get turned off when the family fell behind on bills. When the water was shut off, the boys hooked a garden hose over a tree branch in the yard to take showers.

They were happy and never lacked for food, but the stress of living in the U.S. illegally was ever-present.

Once, as the three young brothers played outside their mobile home, their mom yelled for them to come inside. She closed all the windows, turned off the lights and told them to hush. Agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement were doing a sweep of their trailer park. The family squatted in the tense dark until the threat passed.

Later, their parents explained that they didn’t have legal documents to be in the country. They stressed that the boys needed to stay out of trouble, avoid bad influences and always drive the speed limit. Even a minor infraction could break up the family and send one or all of them back to Mexico.

“That’s the fear you carry each day,” said Darío Medina, 42. “You leave your home and you don’t know if you’re coming back. You may or may not see your family again.”

The family moved into a three-bedroom trailer home in Lake Dallas. Every Sunday, they attended service at Church of Christ and thanked God for the little they did have: food, shelter, health, each other.

“I’ve always told my sons, ‘In your life, put God first,’” said Gonzalez, 41. “Be humble and grateful. Don’t do anything without love. Do that and good things will come.”

Good things arrived in 2014 when the Medina family first became aware of DACA. With the help of an uncle and Leo's mowing money, they applied for the program and paid the fee. When Leo’s acceptance letter arrived, the family huddled around the kitchen table, bowed heads and prayed.

“It was such a blessing,” Gonzalez remembered. “We thanked God and we thanked our church. This was a major reason why we came to the United States. To think they would have privileges we don’t have filled our hearts with joy.”

DACA ‘was truly a blessing’

For the first time, Leo Medina could drive without looking over his shoulder. The newfound protection filled him with confidence. In high school, his grades improved and he volunteered with ROTC. After graduating from high school, he tried to enlist in the Navy but was told by a recruiter he couldn’t join without legal status, even if he had DACA.

Instead, he accepted an entry-level job at Baylor Scott & White, emptying trash bins and carting soiled bed sheets to the laundry room. With money from his first paycheck, he filled the gas tanks of the two family cars and bought new shoes for his brothers.

“It was such a relief,” Gonzalez said. “We could focus on rent and bills, and he could help with all the rest. It was truly a blessing.”

Leo Medina said he cherishes all the opportunities DACA has opened but it hurts him to think that his brother wakes up each morning without the same chances – or protection.

“If my little brother got deported, it would break my heart,” he said.

A year after Leo Medina received DACA, Isai Medina applied for and was accepted into the program, too, paving the road to a good-paying job. He recently enrolled in an online college for cybersecurity that, when finished, will lead to even better pay and stability.

Meanwhile, Carlos Medina struggled in school. He was diagnosed with dyslexia and grew restless in classes. He enjoyed playing left tackle and nose guard for the school football team and powerlifting in his spare time. He dreamed of becoming an industrial welder someday, a job where he could work with his hands and maybe travel.

When he turned 15 and was eligible to apply for DACA, the family was struggling financially and couldn’t afford the $495 application fee. When they finally saved enough to apply, Trump temporarily ended the policy, darkening Carlos Medina’s outlook.

He graduated but didn’t see the point of furthering his studies without legal status. He took welding courses at a local college but, without a decent-paying job or access to scholarships, he couldn’t keep up with the tuition payments. He shelved his dreams and started working odd jobs with his dad.

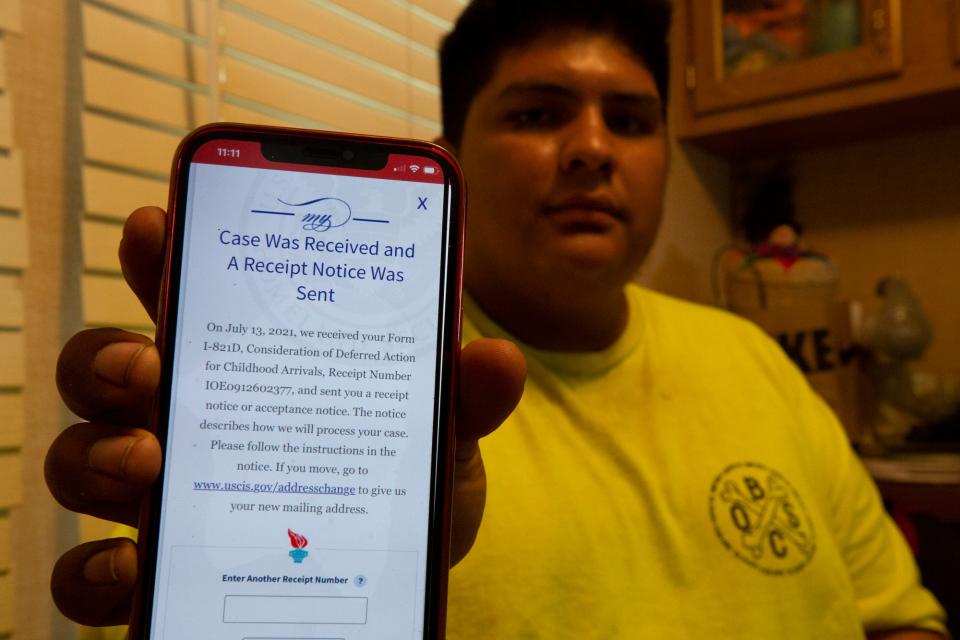

When DACA reopened after the Supreme Court ruling, Carlos Medina reapplied. On July 13, 2021, he received an electronic notice saying his application had been accepted by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Three days later, the Texas judge again slammed the door on DACA.

“I basically feel like the black sheep,” Carlos Medina said. “All I know is America. I was raised here my whole life. I don’t have any memories of Mexico ... It’s frustrating that I don’t have the same opportunities that kids who are born here have.”

‘You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen next’

Darío Medina appreciates what DACA has done for his two older sons but is pained by the fact that his youngest remains in the shadows. The policy's volatile path has left the family dizzy, he said.

“It feels like a roller coaster,” he said. “You don’t know exactly what’s going to happen next.”

After finishing offloading the last of the hale bays, Darío and Carlos Medina returned to the three-bedroom trailer the family still shares in Lake Dallas. Darío Medina always drives: If they get pulled over and handed over to ICE, he said he’d prefer to be the one deported, not his son.

At home, Carlos Medina showered, rested on the couch for a few minutes and then helped his mom shape and cook tortillas for dinner. He doesn’t like video games, he said, because it dulls the mind. In his spare time, he tinkers with the family’s ‘98 Dodge Ram truck.

Carlos Medina said his goals are simple: He’d like to finish his training and travel the country welding pipelines for large companies. He’d like to make new friends. He’d like to buy groceries and help his parents with rent. He’d like to take a flight on an airplane.

He’s learned to live with DACA’s fickleness and realizes that even if he gets it, it might be taken away.

Without DACA status, he plans to continue staying out of trouble and working with his dad to earn a few bucks. God will take care of the rest, he said.

“I’m prepared to live with or without DACA,” Carlos Medina said. “Either way, I’ll keep working hard.”

Follow Jervis on Twitter: @MrRJervis.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: DACA helps some family members, leaves other immigrants struggling