In Ron DeSantis’ Free State Of Florida, His Ear Has A Steep Cost

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ron DeSantis’ first speech as a presidential contender was a dark and broody recitation of the forces he blames for ruining the country. Standing in front of a two-story American flag on a stage in Iowa, he rattled them off: “cultural Marxism,” “woke ideology,” Hunter Biden and, finally, corporate America.

“There was a little business that you may have heard of in Florida,” he said, “named Disney. People told me, ‘Listen, the media’s coming after you, the left — but if Disney weighs in, they’re the 800-pound gorilla. You better watch out, they’re going to steamroll you.’ Well, here I stand. I’m not backing down one inch,” he said to whoops and scattered applause.

“We run the state of Florida. They do not run the state of Florida.”

It’s strange days in the ongoing realignment of the modern GOP. A majority of Republican voters have gone from admiring large companies and financial institutions to reviling them. Presidential candidates are crusading against giant corporations like Bud Light for the crime of acknowledging LGBTQ+ people, and DeSantis has declared open war on his state’s most valuable employer for daring to come to their defense. The Republican Party has a rich tradition of drafting off of hatred for minorities, but never before has it placed them on such a direct collision course with their other primary source of power, the American boardroom.

DeSantis has bet he can ride these shifting currents by styling himself as America’s most vicious culture warrior. His nebulous path to victory depends on peeling support away from the original fake populist, Donald Trump, despite having none of the former president’s charisma. And his fight with Disney offers a way for him to manufacture the illusion that he poses a serious threat to corporate America. For good measure, he has also picked an abstract fight over “woke banking.”

But an illusion is all it is. In interviews with Florida politicians, activists and members of the business community — many of whom won’t whisper a word against him on the record — they describe how DeSantis has catered to special interests as ferociously as he has fought the culture wars. DeSantis wields near-dictatorial sway over his state, which he has used to grant special interests a breathtaking list of favors. He has helped them evade accountability, steamrolled regulations, funded their pet projects, and foisted bailouts and tax breaks onto ordinary taxpayers. Often he does so quite openly. One day after launching his 2024 presidential campaign in a live event on Twitter with its owner, Elon Musk, he signed a law relieving private space companies like SpaceX, another Musk company, from liability for accidentally killing its employees.

In exchange for how he has run the state, DeSantis raised more money for his 2022 reelection than any governor in U.S. history. The funds now power his nascent presidential campaign: Just a few weeks ago, he transferred $82.5 million from his gubernatorial campaign into his presidential super PAC. As a declared presidential contender, he continues to be a fundraising juggernaut, despite donors complaining he has all the personality of wet cardboard.

This doesn’t mean businesses are getting everything they want — it means they’re getting everything DeSantis wants them to have. Despite building his campaign around falsehoods about LGBTQ+ people and fearmongering of woke boogeymen, DeSantis has identified one true thing, which is how few countervailing forces there are against corporations and their political whims. Even in states where Republicans have gerrymandered popular opinion into irrelevance, big consumer-facing companies remain invested in public sentiment. North Carolina’s anti-trans bathroom bill cost the state the NBA All-Star Game. Racist voting restrictions in Georgia did the same for the MLB All-Star Game and draft. DeSantis understands the threat this poses to his ascendance but remains reliant on corporate financial support, which is why his most meaningful attacks on corporate power have all involved reducing it relative to his own.

The word is out. “If you want to get in good with this governor and his team, you have to pay up,” said a Republican consultant in Florida who requested anonymity. The consultant added, “You need to be very careful getting crosswise with the governor.” He will not hesitate to remind you who really runs the state.

A Lock On The Legislature

The Florida 2023 legislative session doubled as the opening act of DeSantis’ presidential campaign. The House and Senate were under the control of a Republican supermajority, which in turn was under the thumb of DeSantis. “I’ve never seen a governor in my lifetime with this much absolute control of the agenda in Tallahassee as Ron DeSantis,” one of his allies, super-lobbyist Brian Ballard, told the Tampa Bay Times.

Virtually every bill that passed somehow furthered his presidential ambitions, allowing him to enter the race without resigning as governor and to conceal his travel records from the public.He signed a ban on gender-affirming care for minors (it has since been blocked in federal court), a six-week abortion ban, a law (likely unconstitutional) allowing non-unanimous juries to impose the death penalty, a vast expansion of private school vouchers and a bill to rename a road after the deceased blowhard Rush Limbaugh.

This is his “blueprint for America’s revival,” a spokesperson for his presidential campaign has said. DeSantis’ pitch is that he will “Make America Florida,” a place where he stomped the “woke elites” by taking on corporate power. “In this environment, old-guard corporate Republicanism is not up to the task at hand,” he wrote in his second biography, “The Courage to Be Free.”

At least that is DeSantis’ carefully crafted mythology. Insofar as you know DeSantis as the book- and drag-show-banning governor, it’s catching on. Other pieces of his legislative agenda — particularly the many bills he signs without cameras present — tell another story altogether.

If you want to get in good with this governor and his team, you have to pay up.

This June, having accepted more than $2 million in donations from Florida car dealerships, he signed a law cementing their profits by banning direct-to-consumer sales of cars. The law contains a notable carve-out for Tesla, which relies heavily on direct sales and is another Musk property.

Another law he signed this month will exempt Minor League Baseball players from Florida’s minimum wage law. When the bill was filed, minor leaguers were at the bargaining table, trying to raise minimum starting salaries above $20,000. “I’ve been covering Florida politics for more than 20 years now, and I have never seen a more mean-spirited piece of legislation than this,” said Jason Garcia, an independent journalist and Florida’s foremost chronicler of pay-to-play politics. “It’s the sort of bill Montgomery Burns would sponsor.” The day after the bill was filed, Joe Ricketts, whose family owns the Chicago Cubs, gave $1 million to DeSantis’ 2022 reelection fund.

Some donors have enjoyed a striking return on investment. In May, he signed a bill discounting insurance for homeowners who install spray-foam insulation that was written by a chemical company struggling to sell spray-foam insulation. The company, Huntsman Corp., its CEO, Peter Huntsman, and his mother, Karen Huntsman, gave DeSantis’ campaign a combined $27,000 last year, and the company hired his ex-chief of staff and ex-economic development director to lobby for the bill.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis pushes his "war on woke" at the 2022 Conservative Political Action Conference in Orlando on Feb. 24, 2022.

Even DeSantis’ messaging bills tend to serve his biggest backers. A key bill DeSantis rammed through the legislature this year prohibits Florida’s public pensions and state-held funds from taking ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors into consideration before investing. ESG investing is a recurring villain in DeSantis’ “war on woke”; at press conferences, he sometimes appears under banners bearing inscrutable catchphrases like “Government of Laws. Not woke CEOs.” But the law serves a second purpose. It also contains a provision that would specifically punish banks that have refused to do business with the GEO Group, a Florida-based private prison contractor and one of DeSantis’ earliest and most steadfast donors.

It didn’t start out this way, with DeSantis openly picking his state’s winners and losers. His path to the Governor’s Mansion ran through a grinding 2018 primary campaign in which nearly every Florida politician and industry association of note supported his main opponent, Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam. After defeating Putnam, DeSantis won the general election by the thinnest of margins, beating Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum by less than half a percentage point.

He used his first year in office to broaden his appeal, seeking funds to raise teacher pay and restore the Florida Everglades, and appointing Democrats to his administration. He deliberately stopped appearing on Fox News, where he had been a bellicose fixture throughout the campaign.

The kinds of political favors he granted were business-as-usual for a state that had always been friendly to its business lobby. The first significant tax legislation he signed — a $2.8 billion reduction in the state’s corporate income taxes — simply continued the cuts negotiated under his Republican predecessor, Gov. Rick Scott. DeSantis even abandoned key parts of his agenda when they conflicted with corporate interests, like when he scrapped a campaign promise to force all Florida employers to adopt E-Verify and check employees’ immigration status.

Privately, though, DeSantis had a plan.

Two weeks after he was sworn in as governor, his campaign already had a strategy for raising donations from high rollers around the country. A private memo, drafted by the fundraising consultant for his Friends of Ron DeSantis organization and uncovered by the Tampa Bay Times, proposed that his first year in office be loaded with “intimate and high dollar gatherings” at donors’ homes and nine-hole, one-on-one rounds of golf for which contributors would be expected to pay $100,000. “This timeframe is relatively aggressive because it is the governor’s desire to fundraise and maintain a high political profile at all times ― inside and outside of Florida,” Susie Wiles, his then-campaign manager, wrote in an email presenting the plan to the governor’s staff.

Fundraising has always been DeSantis’ forte. “You’re talking about a politician whose almost singular skill and dedication is the money chase,” said David Jolly, a former Republican representative from Florida who ascended to Congress around the same time as DeSantis. “It was incredible to see his success because he was a safe freshman in a Republican district, and here he was nationally fundraising with some of the biggest Republican donors — the Ricketts, the Adelsons, you can go down the list — because he was a man in a hurry.”

As governor, he honed this into a science. His in-state travel, the memo urged, should sync up with when ultra-wealthy snowbirds flocked to their homes on Hobe Sound and John’s Island. If he traveled to a fundraiser out of state — he had invitations from Republican mega-donors in Texas, Nevada and New York — DeSantis ought to demand a minimum commitment of $250,000.

Wiles denied to the Times that DeSantis executed the plan, but the facts suggest otherwise. Campaign finance records from his first year in office show he routinely raised six figures in a single day, from just a few wealthy donors at a time. About half of his campaign contributions came from onetime supporters of Putnam. Just a few weeks into his term, Duke Energy was pledging $100,000 for three of its lobbyists to play golf with DeSantis on Biscayne Bay. (“All political contributions made by Duke Energy come from shareholders, not customers,” Shawna Berger, a Duke spokesperson, said in response. Other donors mentioned in this story did not return requests for comment.)

For the eye-popping sums he commanded, DeSantis often spent just a single hour with his benefactors. Supporters have complained over the years that he is impersonal, irritable and downright rude. “He’s a block of wood,” said a longtime Florida insider, when I asked how DeSantis acts in a room full of donors.

Charm was simply not necessary. Along with his fundraising objectives, DeSantis entered office with a tactical plan to accumulate more executive power than any governor preceding him. “One of my first orders of business after getting elected was to have my transition team amass an exhaustive list of all the constitutional, statutory, and customary powers of the governor,” he wrote in “The Courage to Be Free.” “I wanted to be sure that I was using every lever available to advance our priorities.”

It is the governor’s desire to fundraise and maintain a high political profile at all times ― inside and outside of Florida.

The sudden emergence of COVID-19 in early 2020 gave DeSantis an unexpected opportunity to speed-run his plans. Even among Republicans, he distinguished himself for his willingness to politicize a sweeping health emergency. He ended virtually all public safety precautions after just three weeks of lockdowns — declaring, “We will never do any of these lockdowns again” — and resumed his Fox News appearances in order to rail against school closures and, later, mandatory vaccinations. When local leaders tried to impose mask mandates, he signed an executive order invalidating them.

Many governors during that time brought their legislatures into special session, giving elected representatives the ability to help shape extraordinary COVID-era policymaking. Not DeSantis. Instead, he seized total power to set the state’s masking policies and dole out federal COVID funding himself. “The legislature let the governor run roughshod during the state of emergency,” said Anders Croy, communications director for Florida Watch, a progressive organization. The balance of power has never recovered. “Since then, the governor has essentially ruled by administrative fiat.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis vows to keep restaurants open during COVID-19 at a news conference on Dec. 15, 2020, at Okeechobee Steakhouse in West Palm Beach, Florida.

The pandemic forged the belligerent, autocratic DeSantis who runs Florida today. Before, there was always a give and take. The state House and Senate had their priorities, and the governor had his priorities and there was friendly horse-trading. (Republicans have held a trifecta in Florida for 24 out of the last 25 years.) “It is completely different right now,” Croy said. “The fact that everything comes from the plaza level” — meaning, the governor’s office on the Plaza Floor of the state Capitol — “and they’re dictating 90% of the agenda is an absolute flip of how it used to be.”

Now Republicans wanting to vote no on DeSantis-backed legislation had to obtain permission. He had become a household name and a right-wing folk hero, and any lawmaker who put a toe out of line would pay. Using the 2022 elections as a live threat — the governor was hand-selecting midterm candidates to run for the legislature and even local school boards — DeSantis rammed through a bevy of laws that raised his national profile while targeting and immiserating minorities, such as the “Don’t Say Gay” ban on classroom discussions of gender identity and sexual orientation and a ban on the teaching of critical race theory.

“There is no acceptance of the idea of opposition,” said a longtime political organizer who requested anonymity for all the reasons just laid out.“I’ve been around this for a very long time, and this feels different. He shook the shit out of all of them. What is very clear is, from the very top, there is an agenda, and if you fucked with that agenda, it’s ‘I’m going to fuck with you.’”

When Disney Didn’t Get In Line

“Florida is becoming a testing grounds to see how far people will go,” said Sheena Rolle, the senior director of strategy for Florida Rising. “Did he invent crony capitalism? No, but he is a test of ‘Can he get away with being so blatant?’”

The pandemic unleashed this side of DeSantis, too. Early in his first term, DeSantis stacked state boards, commissions and task forces with more campaign donors than did his predecessors. But it was in the years after the pandemic when the list of favors DeSantis doled out became truly staggering.

In 2021, he signed a $2.6 billion corporate tax cut that shifted the burden of refilling the state’s unemployment fund, which had been devastated by COVID, off of Florida’s largest employers and onto ordinary shoppers via an internet sales tax. For the year 2021, the top 100 employers would have owed $193 million more in unemployment taxes if the law hadn’t been in place.

His administration approved a $16.5 million state grant to upgrade a vehicle import facility a few weeks before the owner, JM Family, gave his political committee $200,000. A lottery vendor that gave DeSantis $125,000 was awarded a multimillion-dollar state gaming contract by a DeSantis appointee. The owner of a Key West cruise ship pier donated just shy of $1 million to Friends of Ron DeSantis before the governor signed a law overturning Key West’s ban on cruise ship docking.

There is no acceptance of the idea of opposition.

He signed a bill reducing staffing requirements in nursing homes after the industry raised more than a quarter million for his reelection. Around the same time that Daytona Beach mega-developer Mori Hosseini and another homebuilder, Geosam Capital, gave DeSantis more than $380,000, the Department of Transportation approved an $84 million state-funded highway interchange that will support traffic to their new housing developments.

Rob Walton, whose family owns Walmart and is one of the wealthiest families on the planet, donated $25,000 to DeSantis in April, just days before he signed the first of two new laws that were privately championed by a law firm handling the Waltons’ fortune. The laws increased secrecy around family trusts incorporated and permitted trusts, which the ultra-wealthy use to pass on tax-free inheritances, to exist for 1,000 years. Another law he signed raised the commission that grocery stores and gas stations pocket anytime they sell a lottery ticket. Two of the biggest beneficiaries were Publix, the grocery store giant that has donated $150,000 to DeSantis since he became governor, and Sunshine gas station, whose parent company owns a pair of jets it lends free to DeSantis.

Into this ongoing power trip walked Disney.

It was summer 2022, and the Florida Legislature was on the verge of passing the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, an open assault on LGBTQ+ teachers and students. “Acceptance and understanding in the classroom promote compassion and kindness,” said one Tampa Bay high school teacher. The law would create “a world where their identities are summarily erased.” Among the fearful and outraged were Disney’s 75,000-plus Florida employees and their families. Disney’s then-CEO, Bob Chapek, opted to stay silent until after the bill had passed and all that was missing was DeSantis’ signature. Then he broke his silence and said Disney opposed the bill and was pausing all of Disney’s Florida political donations.

“People forget: They closed the faucet,” said state Rep. Anna Eskamani (D).Disney had made $1 million in contributions to Florida Republicans in 2020. DeSantis was up for reelection in November and entering the most high-stakes fundraising period to date of his political career, the one that would tee him up to challenge Trump. By this time, he had raised $100 million to face an uncontested primary and a field of weak Democrats — “a gaudy figure,” the Sarasota Herald-Tribune called it, traceable to how boldly DeSantis was rewarding his contributors.

Disney itself had enjoyed countless special favors. Just a year before the “Don’t Say Gay” law, the DeSantis administration had worked to exempt the Disney+ streaming platform from a tech regulation bill. Now here was Disney thinking it could threaten him.

In his memoir, he recalled giving Chapek a counter-warning: “You will end up putting yourself in an untenable position.”

Weeks later, DeSantis announced lawmakers would consider a proposal, previously relegated to the libertarian edge of his party, to dissolve the special tax district that allows Disney to self-govern its Florida theme parks. Known then as the Reedy Creek Improvement District, the arrangement allows Disney to avoid many state regulations, raise money using tax-exempt bonds and generally save millions of dollars a year. There are hundredsof special tax districts across Florida, each costing the state revenue, but DeSantis was only interested in attacking this one.

Not even Disney seemed to realize how hellbent he was on getting retribution. When the bill came up for debate, allies with the Associated Industries of Florida and the Florida Chamber of Commerce sat in the back rows, silent. “The thinking at the time was, he’ll do this, he’ll get some headlines, it’ll go away,” said someone familiar with their thinking. His relentlessness also stunned many Florida Republicans, who have worked hand-in-glove with Disney for decades. “I can’t tell you how many Republican legislators there are in the House and Senate who openly behind-the-scenes” — openly behind-the-scenes! — “mock the governor for this fight with Disney,” said a Republican consultant in Florida who requested anonymity.

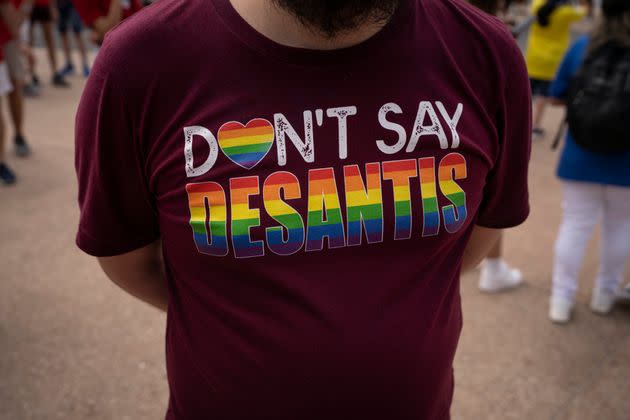

A "Don't Say DeSantis" T-shirt at Disney World's Magic Kingdom on June 3. "Gay Days" at Disney began three decades ago and is one of the nation's largest Pride Month events.

Jolly, the former Republican congressman, said they were missing the point. Grievance politicians have no predictable allies, only temporary friends and enemies. “Trump has ushered in a post-ideological party, and DeSantis is a perfect example of that.”

At the signing of the 2022 state budget, DeSantis line-item vetoed millions in funding for his fellow Florida Republicans’ personal passion projects. He said he was targeting “pork” spending. Around the same time, he approved a sales tax exemption for tickets to Formula One Grand Prix races. The tax break was sought by Steve Ross, the billionaire owner of Miami’s Hard Rock Stadium, who had donated $100,000 to DeSantis one month earlier.

The way that DeSantis has tried to resolve his fight with Disney is telling. (The company and DeSantis are now locked in a legal battle.) A series of laws he signed this year requires the company to answer to a handpicked board of cultural warriors but leaves its tax-exempt status and ability to raise revenue through tax-exempt bonds, which has saved the company millions of dollars, intact. They made Disney weaker mainly insofar as it has to answer to him.

By the time his first term ended, DeSantis had a gigantic seed fund for his presidential ambitions. The Herald-Tribune’s political editor counted 42 billionaires among DeSantis’ donors. (You can add one more to the list: Records show that Todd Wagner, who co-owns 2929 Entertainment with Mark Cuban, is linked to a limited liability company that donated $300,000 to DeSantis a week after his reelection.)

His top donor, the Republican Governors Association, took in millions from companies with business before the state of Florida — such as Florida Power & Light. He cruised to reelection in November having raised $217 million, more money than any governor in U.S. history.

They’re all saying the quiet part out loud; there’s no effort to hide it. It’s just all out in the open.

And he never stopped passing the hat. Members of his administration were texting lobbyists for contributions to his presidential campaign, NBC reported, during the weeks when DeSantis could line-item veto their clients’ political priorities. In addition to the $82.5 million he transferred into his presidential super PAC, his super PAC had separately raised $30 million as of April. (The group will not have to disclose its donors until July 1.)

“Under his administration, crony capitalism has just been given full license,” said Rich Templin, the director of politics and public policy for the Florida AFL-CIO. “They’re all saying the quiet part out loud; there’s no effort to hide it. It’s just all out in the open.”

Whether or not average Floridians are tracking these feudal machinations, they are probably feeling the effects. Last year, Realtor.com ranked Florida as the least affordable state in the country. Rents in all four of Florida’s major metro areas — Miami, Tampa, Orlando and Jacksonville — grew faster than the national average, with rent in some markets shooting up 31% and even 57% year over year. This year, Florida is one of the only places in the country where home prices are still rising. Meanwhile, home insurance prices surged 50% during DeSantis’ first term in office.

DeSantis’ answer to these crises is essentially to offer what the relevant industries want. After Hurricane Ian sent Florida’s insurance markets into a tailspin, he called a special session where lawmakers passed a $1 billion taxpayer-funded bailout of struggling insurers that didn’t put any brakes on insurance prices. “The industry got a wish list of reforms,” said Democratic state Rep. Hillary Cassel. “What have we done for consumers? Nothing. What have we done for insurance companies? Everything.” Florida insurance prices are projected to rise an additional 40% this year.

His moves to address the affordable housing crisis have won broader support but are also limited to market solutions. In the spring, he committed $711 million in incentives to homebuilders to construct badly needed worker housing. The same package prohibited local governments from regulating landlord-tenant agreements in any way. The law preempted rent control and other tenant-friendly measures passed in Democratic strongholds like Miami-Dade County, Pinellas County and St. Petersburg. In Orange County, where the average household spends 37% of its income on rent, the law preempted a ballot measure passed in November that would have temporarily capped rent increases at 9.8%.

“People are sleeping on their children’s couches, literal grown-ass women,” said Roxey Nelson, the executive vice president of 199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, the country’s largest healthcare workers union, who is also an Orlando area resident. David Maldonado, the pastor of Hablamos Español Florida, said members of his congregation have slept in their cars or rental storage units. “I know one woman, with two children, who spent a few nights in a U-Haul truck she rented to sleep in because she had no other option.”

Clouds Over DeSantis’ Sunshine State

DeSantis has a message for his haters: People love it here. He won reelection in a 19-percentage-point landslide and with a strong approval rating while thousands of others voted with their feet. “Florida is the fastest-growing state in the nation,” he said in March at his annual state of the state address. “We did it our way, the Florida way. And the result is that we are the number one destination for our fellow Americans who are looking for a better life.”

DeSantis didn’t invent moving to Florida. Its population has grown faster than the rest of the country in every decade since the 1950s — never faster than in the 1950s, at the dawn of the air conditioner. Still, he’s right. Florida grew about three times faster than the rest of the country from 2021 to 2022, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, with most of its growth coming from the more than 444,000 new residents who were seduced by Florida’s permanent summer, lack of COVID restrictions or 0% income tax.

Rent control advocates for Orange County demonstrate in front of a Florida real estate office on Oct. 22, 2022, in Orlando.

Few people have relocated with as much fanfare as Ken Griffin, the CEO of the titanic hedge fund Citadel. In June 2022, Griffin announced that he was moving his family and the headquarters of his $59-billion-assets-under-management company from his longtime home of Chicago to Miami. Griffin had spent the months leading up to the announcement blasting Illinois leadership over Chicago’s crime rates. (In 2021, when he began complaining, overall crime in Chicago had actually fallen for three years running.) “If people aren’t safe here, they’re not going to live here,” he said. He called his new home “a vibrant, growing metropolis that embodies the American Dream.”

His move dovetailed nicely with the story DeSantis is telling — on the surface. Griffin, whose estimated net worth is more than $36.3 billion, had also just endured a bruising political loss. In Illinois’ gubernatorial primaries, he spent $50 million on a Republican, Richard Irvin, who whimpered to a third-place finish. A Chicago Sun-Times headline dubbed it the “worst political investment in Illinois history.”

“He wasn’t going to have a future of control and influence, politically speaking, in Illinois,” said a source deeply rooted in Chicago’s business community — a reality check that just so happened to coincide with his decision to move to Florida.

When ordinary people daydream about moving to Florida, they think of sunshine, beaches and low taxes, said Croy, of Florida Watch. “When billionaires and large corporations look at Florida, they know they can increase their bottom lines and decrease workers’ wages and not have to worry about regulations from the government.” The latter group has done an extraordinary job of profiting off of the former. And for now, they rely almost entirely on DeSantis’ favor in order to do so.

But as the presidential campaign takes him further away from his power source, there is the possibility that his grip on power will weaken. A majority of Florida’s Republican caucus in Congress have endorsed Trump. His fear tactics don’t work as well on people without business before the state of Florida, and several major Wall Street donors have recoiled from his campaign as early polls show him losing to Trump. Suddenly, he’s not their only option.

Even Griffin is feeling fickle. As of last year, he was DeSantis’ largest donor, having given him more than $10 million, and he backed the idea of DeSantis running for president. But two sources said his enthusiasm waned after DeSantis signed Florida’s six-week abortion ban; he also reportedly disapproves of DeSantis’ opposition to military funding for Ukraine.

“Ultimately, what do people that wealthy want? Control,” said the Chicago source. Griffin blamed his move on crime, this person believed, because what else could he do? “He’s not going to say, I want to be the puppet master, so I’m moving to the place where there are more puppets.”

(HuffPost reached out to Citadel to discuss Griffin and DeSantis generally. In a later lengthy statement, a spokesperson took issue with the idea that Griffin left Chicago because of politics. “Ken’s decision to leave Illinois had nothing to do with Richard Irvin’s campaign. In fact, Ken supported Richard even months after he, his family and many of his senior partners made the decision to move,” the statement said. It asserted that multiple Citadel employees had been the victims of crime in the city. “The truth is that Ken has a deep personal affection for the city of Chicago and it was only with considerable regret that he decided to leave,” the statement added. It also objected to the use of the anonymous sources in HuffPost’s piece.)

Will capital stay under Ron DeSantis’ thumb? Does it matter? A longtime Florida organizer told me her job from now until November 2024 is to “save the rest of the American populace from Ron DeSantis” — but even that might not constitute a victory. Win or lose, DeSantis is taking his brand of authoritarian capitalism on a national roadshow. What would stop a wised-up second Trump administration from copying the Florida way?

“A lot of us in Florida right now are just wondering when the cavalry is coming,” said the AFL-CIO’s Templin. “All of the book banning and privatization of public education — we really feel like we no longer live in the United States.”

In his nightmare scenario, Florida begins to feel familiar again because it’s the same as it is everywhere else.

This story has been updated to reflect Citadel’s full response regarding Ken Griffin’s relocation from Chicago.