"Roots of America" speaker, others tell more on history of the Cherokee

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

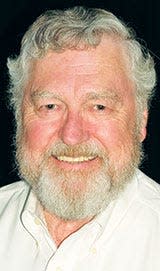

This is about the second in the series of "Roots of America" lecture series, sponsored by the Oak Ridge Breakfast Rotary Club and the Oak Ridge Center for Continued Learning. This one featured a Cherokee woman telling us about the history of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. As I have researched Nancy Ward’s history, who lived from 1738 to 1822, and I have chased a stolen statue of her for over 40 years, I am always happy to learn more about the history of the Cherokee.

Important links:

Learn more about the history of the Nancy Ward statue here: http://smithdray1.net/historicallyspeaking/2006/5-23-06%20Nancy%20Ward%20Statue.pdf.

And here: http://smithdray1.net/historicallyspeaking/2008/12-23-08%20Nancy%20Ward%20statue%20-%202.pdf

And learn about the history of the Beloved Woman of the Cherokee, Nancy Ward here: https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/nancy-ward/.

My interest in history began when John Rice Irwin, the late founder of the Museum of Appalachia at Norris, asked me to take a photograph for the Tennessee Blue Book of an Indian statue on a white woman’s grave in the Arnwine Cemetery in Grainger County. Then he asked me to write a page on the history of Nancy Ward to place alongside the photograph in the Museum of Appalachia. A similar photograph of the Nancy Ward statue and its history are displayed in the Children’s Museum of Oak Ridge.

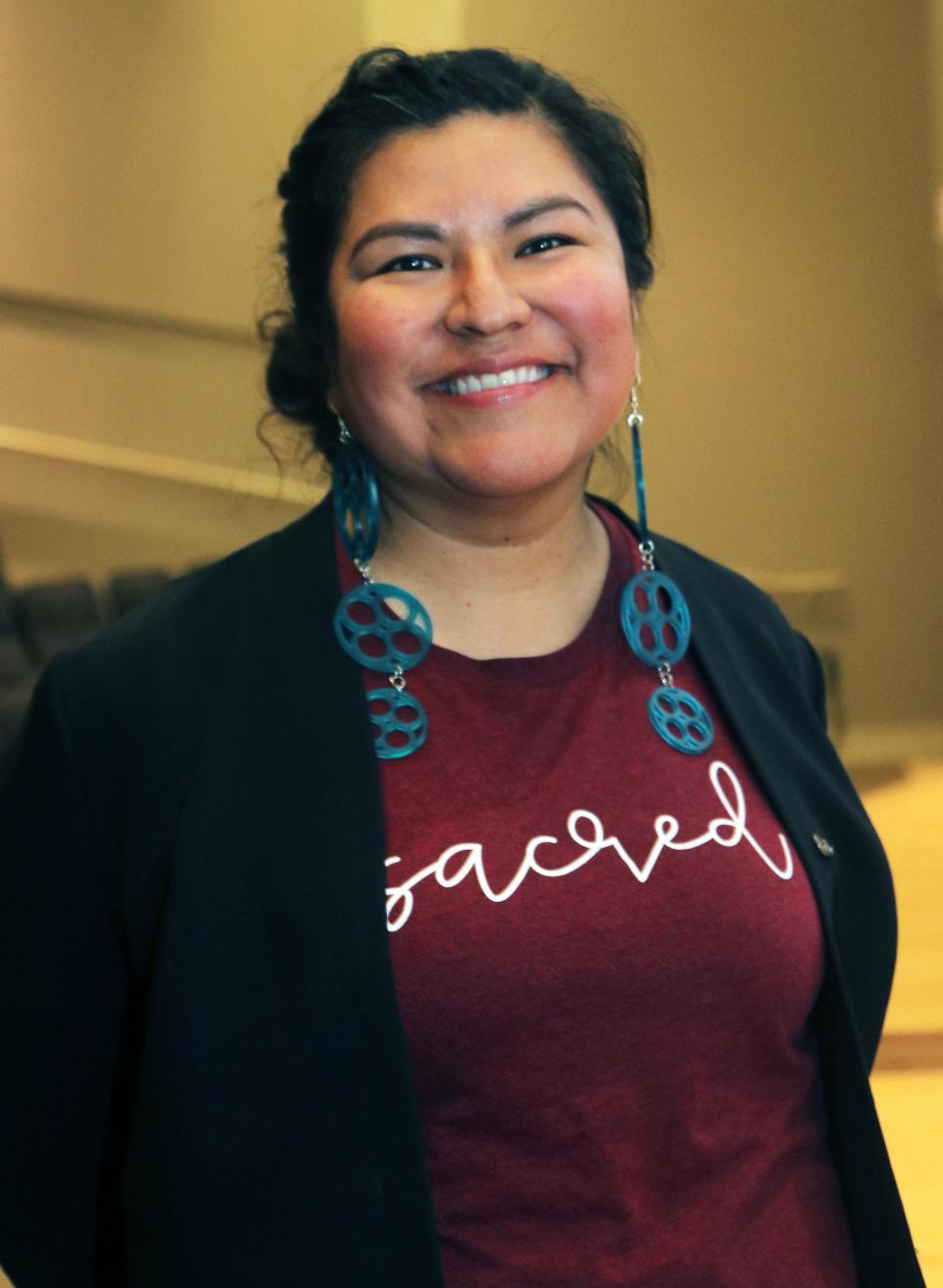

Oak Ridgers who attended the March 9 talk in the “Roots of America” exploration of cultures series learned some interesting details of Cherokee history from Lavita Hill, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Her quest is to restore the name of Clingmans Dome to the original Cherokee name of Kuwohi. She explained the rationale behind the quest and gave an update on the status of the effort.

Here is Carolyn Krause’s summary of highlights in the history of Cherokee and other Indigenous cultures, as presented by Hill and other sources.

***

Many of us have learned from our history books that tens of thousands of Cherokee and other Native Americans in the eastern United States were forced by the U.S. government in the 19th century to move to land west of the Mississippi River. The survivors of the so-called “Trail of Tears” death march made their new homes in Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

So, how did members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) in western North Carolina manage to avoid the death march and remain in their ancestral homeland? Lavita Hill, who lives in Cherokee, N.C., the EBCI capital, gave the answer in her March 9 “Roots of Indigenous Heritage” talk to a large crowd at the Oak Ridge Associated Universities’ Pollard Technology Conference Center auditorium.

But first she started with early history. “Anthropologic evidence suggests that for well over 10,000 years, Cherokee people occupied north Georgia, western North Carolina, northern South Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and parts of Kentucky, Alabama and Virginia,” she said. “Cherokee people maintained a sophisticated network of trade, politics, and culture.”

But after white Europeans arrived in the 1500s on the North American continent, 90% of the Indigenous population was wiped out from exposure to the European urban diseases of smallpox, measles, and flu.

The Cherokees in the eastern United States lost much of their population in the “Contact Holocaust.” That was also the case for the many tribes in the Tennessee River Valley, such as the Shawnee and Yuchi peoples who had lived in the Oak Ridge area (according to David Hackett, an ethnohistorian in Oak Ridge with Yuchi heritage). Later, many descendants of these tribal people identified as and talked like Cherokee Indians to protect themselves from being considered enemy “savages” by the U.S. government, which had a friendly relationship with the Cherokee Nation.

Before the Contact Holocaust, Hackett wrote, “The Yuchi were the priests and peace chiefs among all the tribes, as well as the traders of salt and other commodities. For this reason, many Yuchi villages were scattered up and down the system of trade trails, but their main seat was in the Tennessee River Valley where they had salt-making operations at Saltville, Oliver Springs, and Rhea Springs, among others. The salt trade made them quite wealthy, and the priesthood gave them political power.” Hackett stated that “Tennessee” is a Yuchi word that means “brother of waters.”

Concerning the Cherokee people, Hackett wrote that they “considered Tennessee only as their hunting grounds. They were closely allied with the British and Americans and thus considered ‘somewhat civilized.’”

Hackett stated that the U.S. government found it convenient to deal “only with the accommodating Cherokee puppet government while ignoring the other tribes and viewing them as merely part of the Cherokee Nation” because instead of speaking their native languages, the tribal members adopted Cherokee as their common language.

In the 19th century, the Cherokee and other Indigenous peoples in the eastern United States suffered a catastrophe at the hands of the white U.S. government, according to Hill. Some 50,000 Indigenous people, including 15,000 Cherokee Indians, were forced to walk to the west of the Mississippi River, as mandated by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Thousands died from brutal treatment, starvation, exposure, and cholera between 1830 and 1850.

Hill said that a reason for the removal was the discovery of gold on Indian land. However, Daniel Feller, distinguished professor in the humanities emeritus and editor/director emeritus of “The Papers of Andrew Jackson,” who was quoted in a former Historically Speaking column, stated in a talk in Oak Ridge that the chief reason for the Indian deportation was to free up land so white settlers could grow more cotton. Cotton was a major source of income for plantation owners who relied on the free labor of enslaved Black people.

Removal of Indians started under Munroe ... then Jackson

Feller said that Indian removal started under President James Monroe, who told Congress, “It is good for the Indians,” and ended during Martin Van Buren’s presidency when the worst abuses happened as “the Cherokees were rounded up by military force and compelled to move to Oklahoma.

“The Indian Removal Act that Congress passed in 1830 loosely gave President Jackson the authority to do what he wanted to do,” Feller added. “It was the only major piece of legislation passed during his entire eight years as president at his particular urging.”

The official place of origin of the “Trail of Tears” death march was New Echota, Ga., which was established in 1825 by the Cherokee national legislature as the capital of the Cherokee Nation.

“The original capital had a bicameral legislature, a courthouse that housed the Cherokee Supreme Court and a printing press that published a newspaper,” Hill said. “It was a bustling town that has been preserved as the New Echota Historic Site by the state of Georgia.”

The Cherokee people who survived the Trail of Tears march built a new life in Oklahoma and reorganized themselves as the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians and the Cherokee Nation, which today is the largest tribe in the United States with more than 450,000 tribal citizens worldwide and almost 150,000 in northeastern Oklahoma.

But, Hill said, the ancestors of many members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians - a separate federally recognized Indian Tribe that now has 17,000 members - remained in the mountains in what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

“Our 800 ancestors avoided removal by fleeing into the mountains and hiding in the caves in hollers the white soldiers were unable to reach because they lacked the knowledge of the land the Cherokee people had,” Hill said. “The caves, crevices and difficult terrain of Kuwohi and the surrounding mountains were well known to Cherokee people and provided sanctuary and a place to hide out.”

That’s one of the reasons why EBCI members like Hill are campaigning to change the name of Clingmans Dome in the national park back to the mountain’s original name – Kuwohi. In 1859 the tallest peak in Tennessee and the Smokies had been renamed after Thomas Clingman, a Confederate brigadier general and member of Congress.

Hill asserted that the Cherokee ancestors also were able to remain in their homeland because they were smart enough to “develop friendships with the right federal agents and use the law to their advantage. We hid in plain sight. By the 1830s, many of our ancestors had become well adapted to European ways.”

After Indian removal, “the legal status of the Cherokee people who stayed in the East and barely got by farming the land was uncertain for decades,” Hill said. “We were denied rights to become citizens, to own property or to vote. Our Qualla Boundary that we call home today wasn’t given to us by the U.S. government. Our ancestors pulled their money together and gave it to a friendly white lawyer who purchased the land and held it for our people to live on.” It is now a land trust supervised by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The Cherokee people lacked legal status until 1924 when Congress passed a law that made all Native Americans U.S. citizens with the rights to own property and vote in local, state, and federal elections. Today EBCI is a wealthy tribe, thanks partly to the two casinos it owns and operates. That’s why tribal members have more time to seek fairer treatment for their people such as restoring the name of their sacred mountain.

***

Thank you, Carolyn, for the review of the "Roots of America - Indigenous Heritage" program. During the question-and-answer session after Hill’s talk, her husband, Chris Siewers, joined her on stage and added insight into the governing structure as well as the benefits of belonging to the EBCI. He explained about such things as education being free for all members regardless of what school they attend and no matter how many advanced degrees they pursue. Medical services are also free to members of the tribe.

It was a pleasure getting to know them and learning more about their history. They are confident the name of the mountain will be returned to the original, Kuwohi, as they are not meeting any resistance from anyone other than one man who is descended from General Clingman. All locations where they have voiced their desire have been supportive.

Their next step is to submit the recommendation to change Clingmans Dome to Kuwohi to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, a federal body created in 1890 and established in its present form by Public Law in 1947 to maintain uniform geographic name usage throughout the federal government. An example of recent action taken by that governing body is Secretary’s Order 3404, which requires some 660 places to change the name to remove the objectional term “squaw” from the name.

You readers might like to learn more about the effort to change Clingmans Dome to Kuwohi here: https://www.bpr.org/bpr-news/2022-08-04/support-grows-for-renaming-clingmans-dome-to-original-cherokee-name-kuwohi

When you read this be prepared to learn about the awful truth of the Boarding Schools where many of them have cemeteries where Indian children were buried who died while at the schools: https://www.bpr.org/news/2021-07-16/miss-cherokee-to-host-walk-in-honor-of-indigenous-children-who-died-at-residential-schools

While the Trail of Tears is a well-known atrocity, as you can tell, there are more things to be ashamed of regarding how the indigenous people have been treated. I am glad to be a part of helping bring the "Roots of America" to our attention, Upcoming programs are listed below:

Hate crimes, immigration focus of upcoming "Roots" lectures"

On Thursday, April 20, Special Agent Martha Manuel of the Federal Bureau of Investigation will speak on “Roots of Hate Crimes in America” with a focus on ethnic and religious persecution. Hate crimes against Asian, Black, Jewish and LGBTQ peoples have increased in recent years.

On Thursday, May 23, the final “Roots of America” presentation of the year will be a panel discussion devoted to “Roots of Immigration.” Current local and national Latino immigration issues will be highlighted by Madeline Rogero, past mayor of Knoxville; Claudia Caballero of Centro Hispano, Patricia Robledo of Knoxville Schools, and Arlene Amarante of Lincoln Memorial University’s Duncan School of Law.

D. Ray Smith is the city of Oak Ridge historian and writes a weekly column, "Historically Speaking," for The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: "Roots of America" speaker, others tell more about Cherokee history