Rosa Parks exhibition presents civil rights hero in her own words

“I had been pushed around all my life and felt at this moment that I couldn’t take it anymore. When I asked the policeman why we had to be pushed around? He said he didn’t know. ‘The law is the law. You are under arrest’. I didn’t resist.”

Neatly handwritten on yellow paper, though with six corrections, this recollection was probably set down shortly after Rosa Parks’s arrest for refusing to surrender her seat on a crowded bus to a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama, on the evening of 1 December 1955.

It is now among 90 items – writings, reflections, photographs, records and memorabilia – that go on public display on Thursday in the first exhibition of Parks’s personal collection at the Library of Congress in Washington.

The young woman’s decision to disobey a law requiring black passengers to give up seats to white passengers when the bus was full was a milestone in the civil rights struggle.

It triggered a 381-day boycott of the Montgomery bus system and led to a 1956 supreme court decision banning segregation on public transport.

Jane Gunter, 80, a white woman, was on the bus that day, recently married and pregnant. “I sat down on the long seat behind the driver and was lost in my thoughts,” she recalled on Wednesday, having travelled from Atlanta for a first look at the show. “I was alone and all of a sudden the commotion started when this big man got up in front of me and was looking down the aisle and shouted out, ‘You gotta let me have that seat!’

“I said, ‘She can have my seat!’ And when I did that, a tall, fair-skinned man pushed his knees into mine and said, ‘Don’t you dare.’ At that time women did what men said, period, no discussions. I sat down and when the driver got off to call the police – we didn’t have cellphones back then – he had to use a payphone and he demanded that all of the riders get off the bus.”

Parks was arrested but it was the start of a lifelong friendship with Gunter, who has run a ministry that takes care of the poor for 38 years. “She was a great woman, strong but tender. She reminded me of what a grandmother would look like. She had wisdom but yet she was a lot of fun,” Gunter said of Parks.

Parks died aged 92 at her home in Detroit, Michigan, in October 2005, and became the first woman to lie in honour in the US Capitol Rotunda in Washington. “She would have been happy,” about the election of Barack Obama, the first black president, Gunter said, but “I have no idea” what she would have made of Donald Trump.

Although Parks has been generally framed as a quiet seamstress defined by the bus incident – it even featured in Doctor Who last year – Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words, which has been in the works since the library received the collection on loan from the Howard G Buffett Foundation in 2014, makes clear that it was merely one episode in the life of a rebel with a cause.

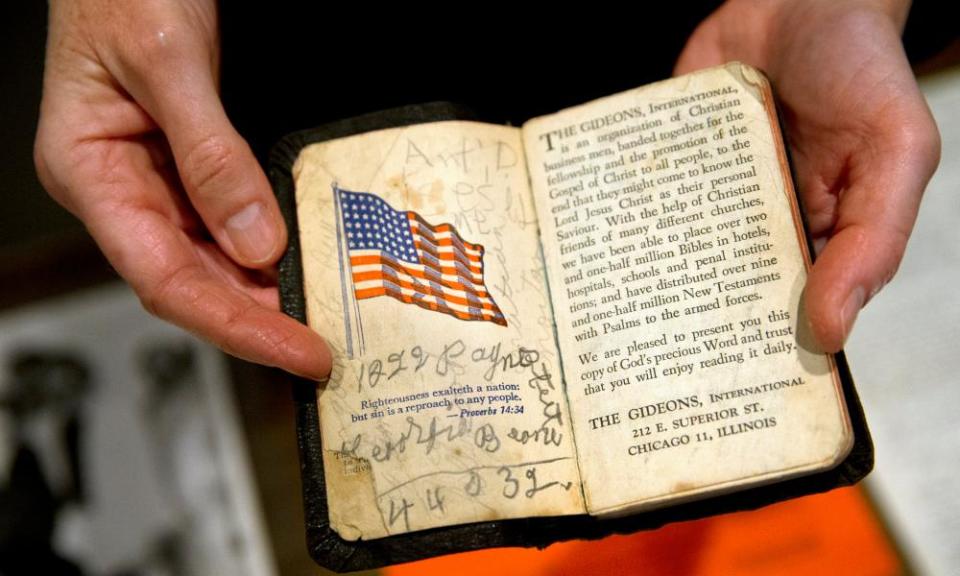

Exhibits include the Parks family Bible, her account of “keeping vigil” with her grandfather to protect their home from the Ku Klux Klan, a manuscript in which Parks recalls a childhood encounter with a white boy who threatened to hit her, documentation of the Montgomery bus boycott, a handmade blue dress from her wardrobe, letters to congressman John Conyers when Parks worked on his congressional staff from 1965 to 1988 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded to her at the White House in 1996.

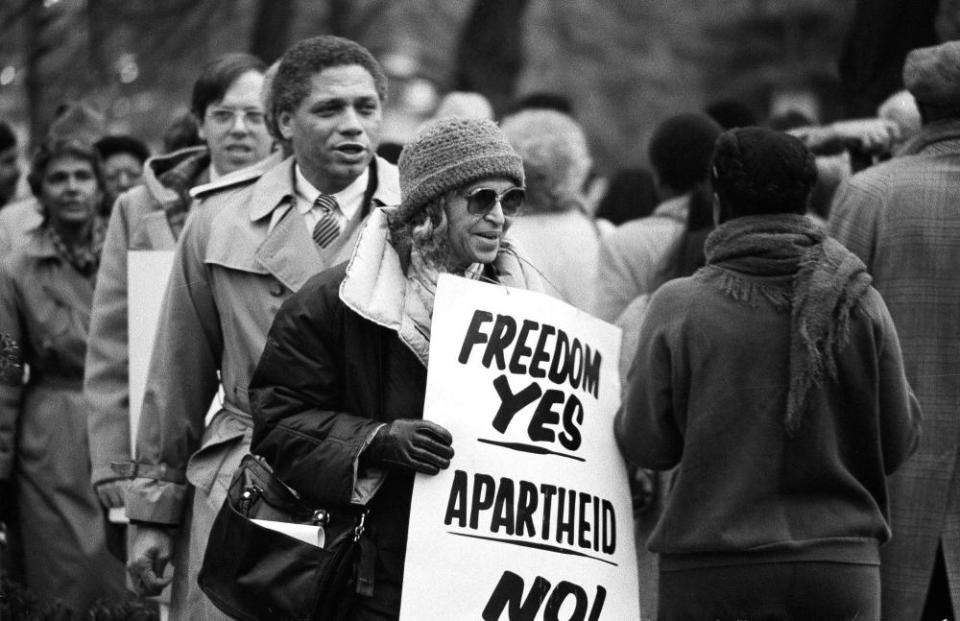

Together they tell the story of a woman who advocated for racial equality and the rights of women, workers and prisoners and who affirmed the Black Power movement, which evoked her grandfather’s Garveyism. She spoke out against apartheid in South Africa and other injustices around the world.

In one letter, Parks writes: “I would rather be lynched than live to be mistreated and not be allowed to say ‘I don’t like it.’”

Adrienne Cannon, the curator of the exhibition, said: “We want to present her as a seasoned, lifelong activist and we also want to show that’s not all of who she was. She was a woman. She was a wife. She was a mother. She was a daughter. She was an aunt. She was a young girl who attracted the boys and she went to dances and parties.

Cannon, Afro-American history and culture specialist for the library’s manuscript division, added: “The power of this collection is that it reveals the truth of a public figure that we thought we knew, that we discover we didn’t really know. That’s the power of any real manuscript collection: that surprise.”

Parks saved money by being an early recycler of papers, aluminium foil, jars and tea bags. She wrote one note on the back of a pharmacy bag. The exhibition includes some handpicked quotations. One says: “I want to be remembered as a person who stood up to injustice … and most of all, I want to be remembered as a person who wanted to be free and wanted others to be free.”