He rose from RI becoming the New York Times' star restaurant reviewer; then depression hit

Glance inside most newsrooms, and the word "scruffy" might come to mind for many who work there.

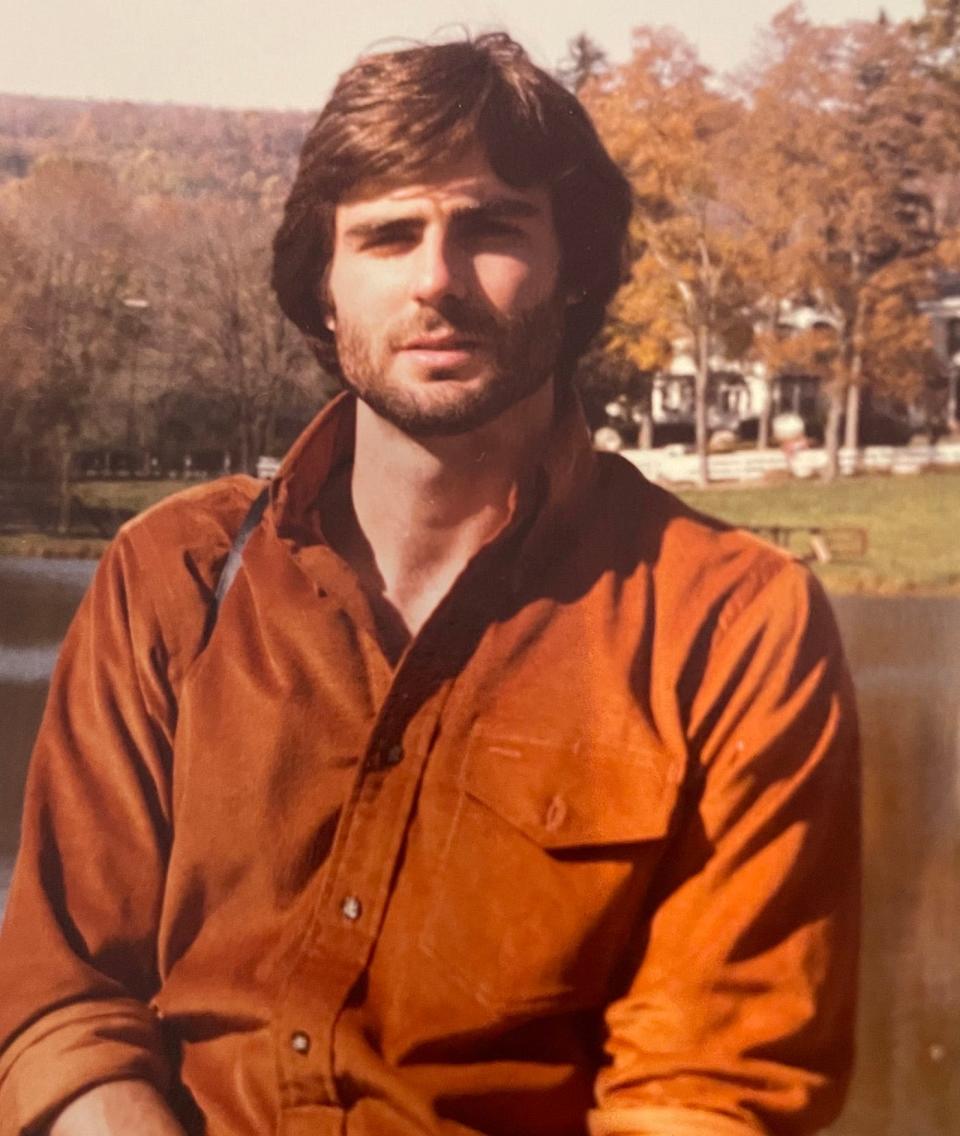

But Bryan Miller was different, more fashionable, and a humble guy. He was a fellow reporter at the Providence Journal during my early years here. I remember his well-groomed hair, tortoise-shell glasses, good pedigree: Colgate undergrad and a journalism master's from Columbia University.

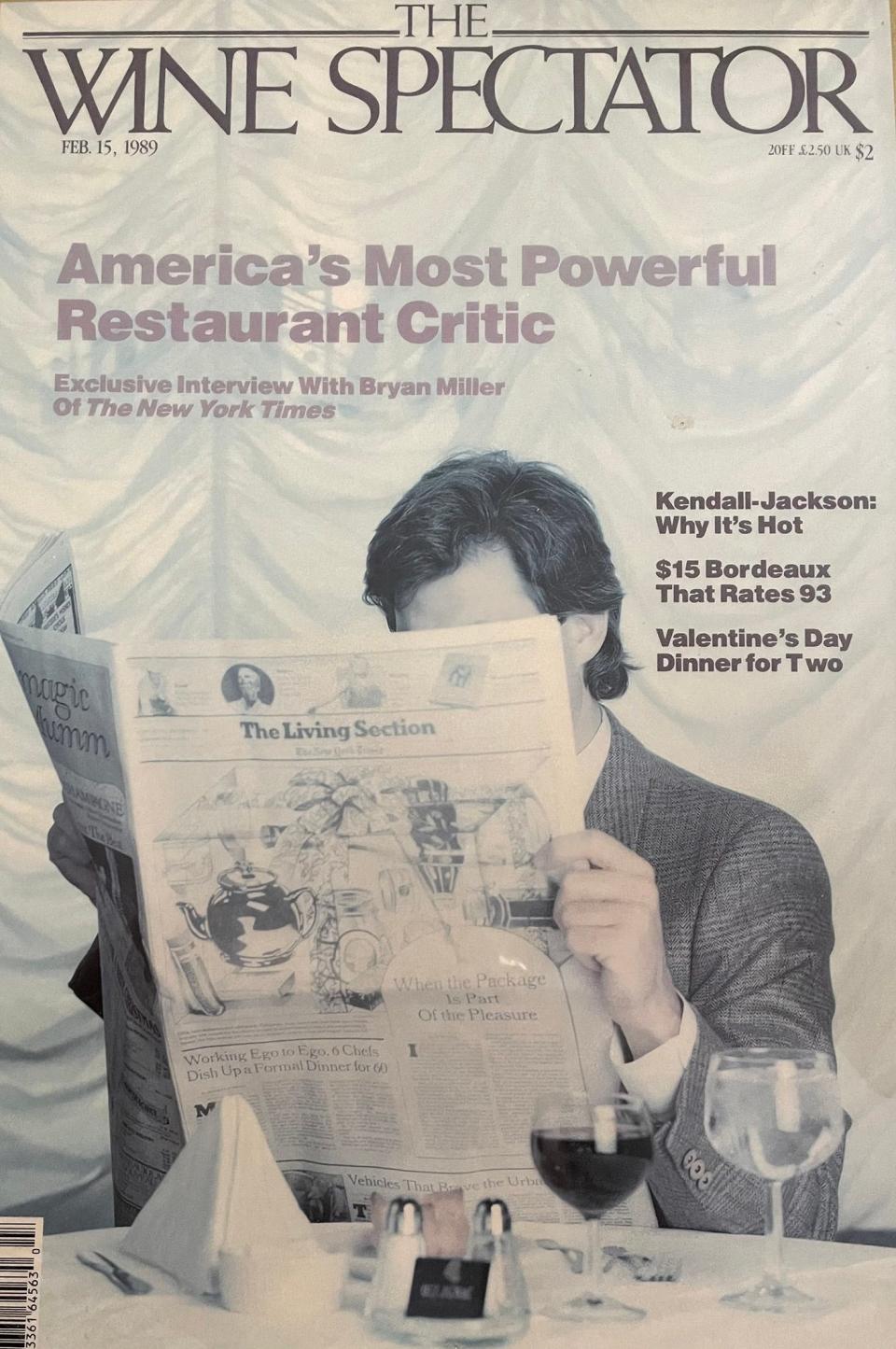

I thought he’d go far, and he did, becoming The New York Times' restaurant critic, one of the top food-writer jobs in the country.

You never know which way a journey can turn.

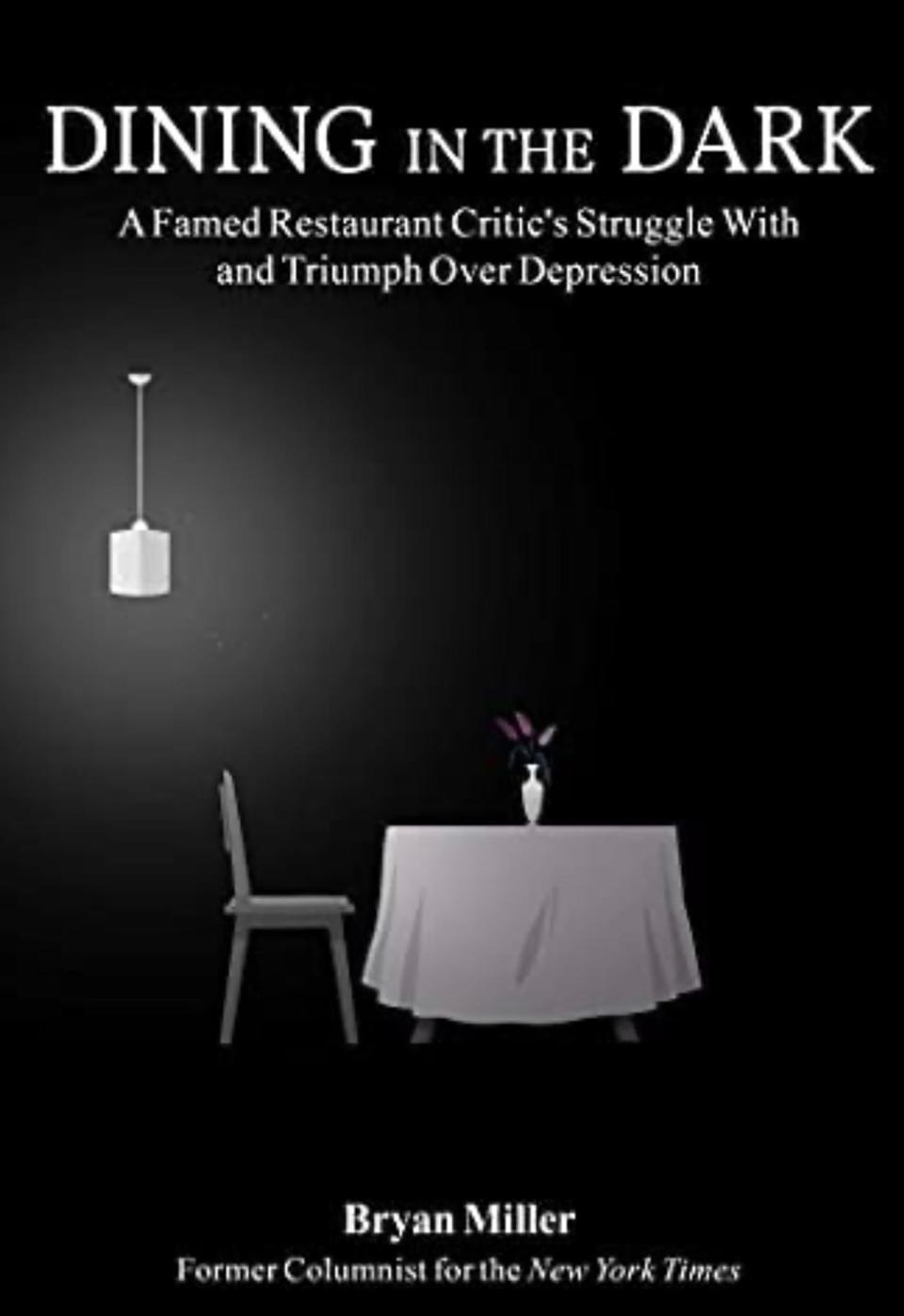

I lost track of Bryan and was recently surprised to see a new book by him about how his life was nearly ruined by depression.

It’s called “Dining in the Dark,” and quite a read, with some lovely Rhode Island moments.

I decided to reach out to him, more as a colleague catching up than a formal interview.

With the help of electroconvulsive therapy, young girl with autism now leads a fulfilling life

He’s now living on his own in a modest rental an hour or so north of Manhattan. He told me the depression wiped him out financially, too, so the spacious farmhouse he once owned in scenic Rhinebeck, New York, is long gone.

Bryan got a bit wistful hearing from a former Providence colleague. Rhode Island, he said, was the best place he’s ever lived – he loved his time on the East Side and in a cottage near the water in Warren.

He remembered the two of us going to lunch 45 years ago – probably at Murphy’s Deli around the time I’d been offered this column, and I was worried I wouldn’t be up to it.

Bryan had a general assignment beat and, on the side, was studying culinary arts at Johnson & Wales. That helped him get aboard The New York Times in 1982 as a food writer, doing recipe and travel pieces.

In 1984, he got the paper’s prestigious restaurant reviewer job.

That’s where I left off with him – when he was at the mountaintop in his field, making good money with added radio and TV gigs. He was a legitimate star.

“So Bryan,” I asked, “what happened, man?”

“Just a rogue wave,” he said.

He’d never before had depression, and woke up one day in January 1984 slammed by it. That seems a dramatic word, but it’s how Bryan describes it.

“I felt dizzy,” he said, “I tried to read the paper but couldn’t understand it.”

Listening to him was an education. I’d always felt depression was what the word implies: a deep despondency. Which it can be, of course.

Enjoy reading?: New book will reveal secret identity of notorious Providence Journal editor John Rathom

But Bryan said one form of it is like a dimmer switch "depressing" your brain activity, and you’re in a barely functional fog, then overwhelmed with anxiety because of it.

He thought it would pass, but days went by and it didn’t. He worried it could be a stroke.

He was finally diagnosed with bipolar syndrome – except for Bryan, there were no manic phases. Instead, he’d go days in that miserable fog, then feel normal for a bit, but soon the depression was back.

“Emily Dickinson called it a funeral in the brain,” he said.

Doctors told him something had thrown off his neurotransmitters.

She couldn't stop one man's jump: Now she's fighting to add suicide barriers to RI bridges

“Under the hood,” he told me, “things had gone wacky.”

He was so worried people would notice and judge him, it turned into crippling social anxiety.

It went in intervals – 10 days comatose, then 10 feeling decent and productive. Because of that, Bryan managed to soldier through it for years.

“Winston Churchill,” he told me, “said, ‘When you’re going through hell, keep going.’”

That’s what he did, trying to live up to his label of star critic. But life was arduous.

During normal phases, he could finish a restaurant review in a few hours, but when depressed, it took days.

“I’d write two paragraphs, lie down, take a walk, everything was so painful.”

He was prescribed various medications, but none helped; neither did electroshock

His star status seemed to shield him from second-guessing by bosses, but by 1995, he’d become a wreck.

One day, he got his annual review, which finally went there.

“He seems to have lost enthusiasm,” it said.

It was during a bad spell, and it tipped Bryan over.

“I got up from my desk and walked out the door,” he said.

Drawn to Rhode Island: Why 7 couples uprooted their lives to move here

It was that abrupt. He’s still not sure what his colleagues thought.

His marriage fell apart, too. He later remarried, but that didn’t last either.

Finally, years later, around 2005, he found a psychiatrist who figured out a cocktail that worked for him, involving 121 pills a week. They included lithium and others to boost serotonin.

That’s also when his son was born, which made a big difference, as well.

Patinkin: Warmongering Providence Journal editor is part of a long line of RI rogues

Through talk therapy, he has since figured out his depression stemmed in part from the suppressed trauma of his father dying of lupus when he was 3.

“Children don’t understand death and can feel a culpability,” he said. “What did I do?”

It festered underground for decades. Bryan likely was also prone to imbalanced chemistry, and the two factors finally came to a boil.

“I was carrying a time bomb for 30 years,” he told me, “and one day it just went off, and that sparked a biochemical thing and the whole house of cards came down.”

That’s part of the message of “Dining in the Dark": the power of buried childhood trauma.

I asked if he’s going to be OK.

Yes, he said, the depression is managed, and behind him. Finishing the book was a big achievement and it’s freeing, he said, to put out your truth. He also gets a lot of joy co-parenting his son, a high-school junior who’s beginning the college hunt.

But a part of him feels he’s back to where he was at his career’s start – freelancing and looking for opportunities.

We said goodbye, with hopes perhaps of crossing paths one day for another lunch, 45 years later.

After I hung up, I sat at my desk quietly, thumbing through Bryan’s book, realizing that even for those who seem at the mountaintop, you never know which way a journey will turn.

mpatinki@providencejournal.com

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Depression derailed New York Times' restaurant reviewer Bryan Miller