Rosemary Kaul, groundbreaking L.A. Times photojournalist, dies

Inspired by a trip to Guatemala, Rosemary Kaul moved to a pocket of Los Angeles where Central Americans found refuge from the civil unrest and violence that ravaged their home countries.

Kaul rented a studio on 12th Street in Pico-Union where she'd live for nearly two years. A single bed and a leafy schefflera — the only thing passing for green space in a concrete-dense neighborhood — took up most of her living space.

Struck by the poverty in the area, the Los Angeles Times photojournalist wanted to capture how hard it could be to begin a new life. She wondered if life in L.A. was truly better for them, but later realized the story was the people themselves.

“They have a spirit that really comes through in their faces,” she told KCET in 1991.

Sensing her genuine sincerity, Pico-Union accepted her as one of their own. Neighborhood children kept an eye out for her company vehicle. Locals chatted with her as they washed clothes in the laundromat. Other tenants in her building invited her over for dinner, offering their best home-cooked meal.

Peers and loyal readers lauded her Pico-Union photo essay. “Having grown up in this area, it is refreshing to see a sincere humanistic portrayal of this community by The Times,” Arturo Vargas, then-director of outreach and policy for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Los Angeles, wrote in 1991.

In an era when institutions, including The Times, overlooked marginalized communities, Kaul used her lens to chronicle their lives and help capture their humanity in a manner others could understand. She was part of a cadre of journalists who shifted their approach to the job, questioning the significance of what an event said about greater Los Angeles. Throughout her career, Kaul's hard-charging and vibrant personality helped inspire the next budding photojournalists in the industry.

Kaul led the charge in her approach to photojournalism, showing empathy and care for sources, said Iris Schneider, a former L.A. Times photographer and longtime friend.

She "didn't really want to just go in and out in some sort of voyeuristic way," Schneider said. "But she really wanted to know what it was like on a gut level to live there and experience that neighborhood and feel what the people were feeling in terms of how hard it was to start over and start a new life."

Always a free spirit, Kaul died of health issues on March 31, said her daughter, Marjo Garrison. She was 80.

Kaul grew up in a tiny town in southern Indiana, but had an itch to see the world. Riding her pinto horse, Beauty, bareback provided her a temporary sense of escape. She was the first in her family to go to college despite pushback from her parents.

Freelancing for Chicago’s Star Publications, a small group of newspapers, was Kaul’s first big break. She commuted on a crowded expressway from her home in Arlington Heights to Chicago Heights until she was hired full-time.

John Murphy, Kaul’s mentor who worked as darkroom process manager, was in awe of her passion and commitment to her job all while raising three children as a single mother.

“If you have to ask Rosemary how she did it, you’ll never do it,” he said. “Because you have to be born with it, struck with it, bitten by a muse. She was just really interested in everything about photojournalism and she could not get enough.”

By 1982, the L.A. Times poached Kaul.

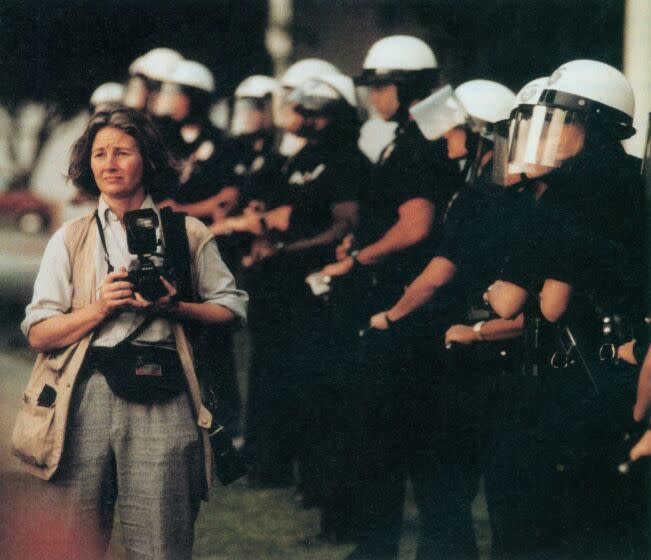

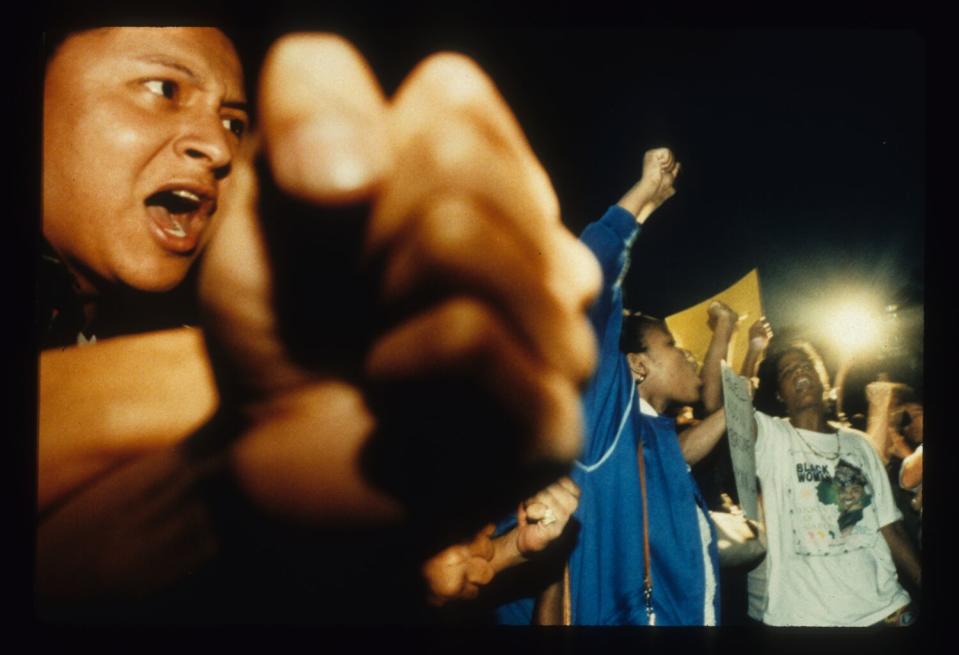

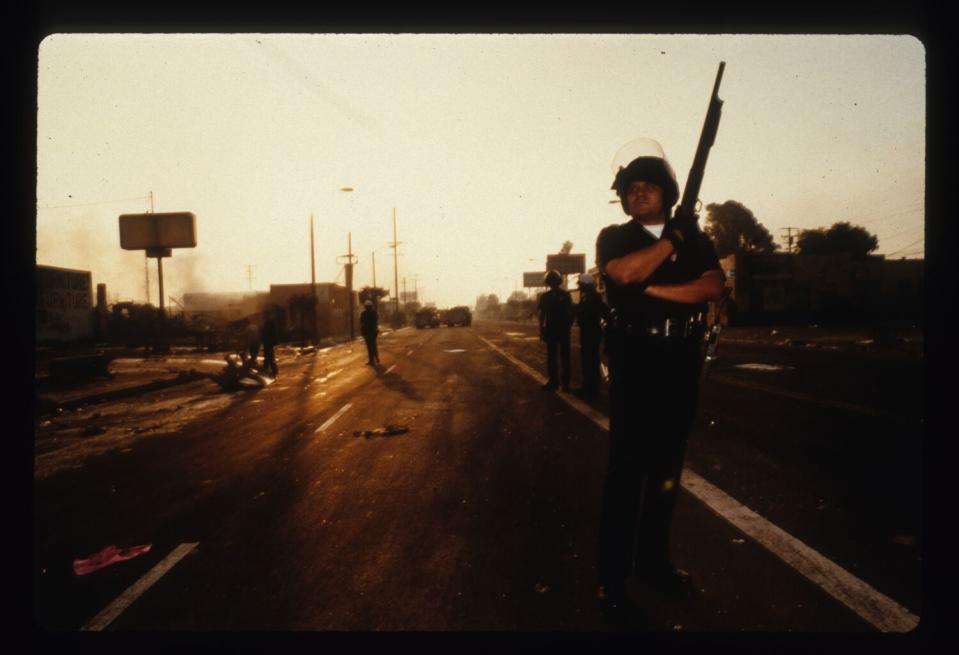

There, she flourished. Kaul was among the first photographers in the streets when the Rodney King verdict was announced. She captured images showing the rage of those congregated near the Los Angeles Police Department headquarters in Downtown L.A. Her colleague Mel Melcon helped her return to the office just in time for him to get photos of the crowd smashing the windows of The Times’ first-floor offices.

Her photograph of the first oil-coated bird found in Prince William Sound in Alaska, illustrating the disaster caused by oil tanker Exxon Valdez, earned her a World Press Photo award.

Following the riots, The Times created the City Times, a weekly publication to cover L.A.'s inner cities. Kaul volunteered to serve as photo editor and became a mentor to the new generation of photojournalists.

Family, friends and colleagues were quick to highlight Kaul’s natural ability to connect with her sources.

Bob Chamberlin, a Times colleague, said he sometimes got the sense she suffered whenever she told a story because she cared that deeply about her sources and carried their feelings, too.

In one instance, Kaul interviewed a mother who was baby-sitting six children so their moms could go to work. The woman, Chamberlin recalled, described feeling the happiest in her life.

“To us white guys, this woman looked like she was disadvantaged,” Chamberlain said. “She’s a migrant, she’s probably illegal. She’s living in freakin’ L.A. and she’s stuck all day inside a tenant slum apartment with a bunch of kids. And that looked like it was rigorous, set-upon, dangerous living. And Rosemary put a human face on that made it approachable and understandable.”

Readers felt similarly. Some wrote to The Times, imploring them to dedicate more space to stories from the inner cities, an area often viewed with a negative lens.

“All we ever read about predominantly African-American neighborhoods are shootings at liquor stores, quarrels with Koreans, drug abuse and police brutality,” wrote Jan Kovaleski in 1991. “I’m aware that all this is real and exists and needs to be told, but for the well-being of young black kids growing up in poor neighborhoods, there needs to be another story told also — the story of mothers and families and neighbors that care about doing something good and positive.”

As photo editor for City Times, Kaul gave Francine Orr her big break.

Orr’s first assignment was to photograph a woman in front of her razed home. Standing in front of the rubble, the woman broke into tears and asked Orr to refrain from taking her picture until she could compose herself. The green photojournalist obliged.

Kaul, a veteran journalist, was livid with Orr’s work and told her to document the truth before her.

“She was a tough editor, and she was the right editor for me and her words were the right words for me in that moment,” said Orr, now an award-winning photojournalist with The Times. “And every single day since that day, I have Rosemary’s voice in my head, reminding me that even if I’m confronted with really difficult things, to do my job — and my job is to document the truth, document what’s right in front of me, even though it can be a very difficult as a photojournalist to do your job.”

Kaul later sought out a trusted colleague to mentor Orr because she didn’t have the time to do it herself.

In 1994, Kaul ended her career with The Times. She took a buyout once her migraines were too difficult to manage with her workload.

Always looking for her next creative outlet, Kaul pivoted to homebuilding. She researched Earthships and straw bale construction.

Kaul found her ideal place to build a home miles away from the closest town in New Mexico. Solar architects helped execute a blueprint for her eco-friendly home, and she built a straw bale house with solar electricity and passive solar heat.

“My mom jumped into everything with both feet. There was no halfway of doing anything,” Garrison said.

While living in New Mexico, she helped establish a community garden and briefly worked for the Albuquerque Tribune before health problems forced her to leave.

Later, she lived in a tent in Yosemite for a season until she moved in with Garrison in San Gabriel.

As her health continued to decline, Kaul took up oil painting and mixed natural elements such as pieces of wood into her artwork. Colleagues and friends stayed in touch with her over the years, sharing their latest photo work or treating her to lunch.

“Nothing stood in her way,” said Al Seib, a colleague who first worked with Kaul in Chicago and later L.A. “Rosemary is a tour de force story, a history that’s [not often found] in our lifetime.”

Now a mother herself, Garrison is hoping to lead in her mother’s example and follow her heart.

“Follow your passion and it’ll all figure itself out,” Garrison said. “She just really wanted you to do it. To not waste your life or wait for something.”

In addition to Garrison, Kaul is survived by two other children, Greg and David; and her brother, Bill Messenger.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.