Royal Mail is broken, and nobody has a clue how to fix it

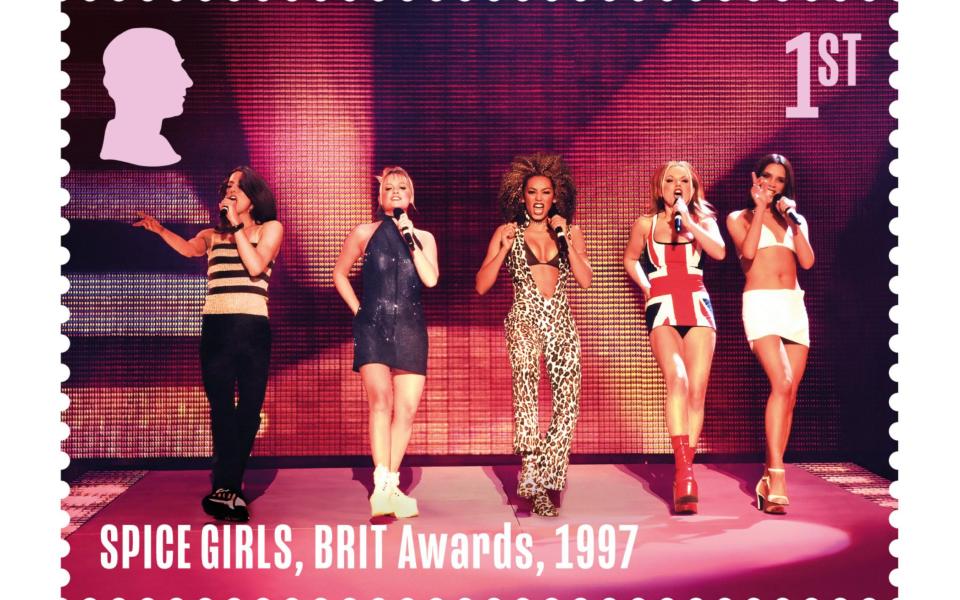

Roll up, roll up for your first day cover of Royal Mail’s latest set of postal stamps – a time limited series of ten photographic images celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the formation of the Spice Girls.

As is normal for new issues, the girl-band stamps are being promoted by Royal Mail partly as a collectable for keen philatelists – but with growing reason, for the primary purpose of stamps, which is to pay for postage, is dying on its feet.

The number of letters we send and receive has fallen by nearly half over the last decade, as people and businesses increasingly swap to digital alternatives. Reductio ad absurdum, there will eventually come a day when stamps will be for collectors only.

Drilling down into the detail of the statistics, the numbers are stark. Twenty years ago, UK households received an average of 14 letters a week; today it is just four, with the overall number of letters delivered per year declining from 20 billion to just 7 billion, a drop of almost two thirds.

As the numbers fall, the average cost of delivery rises commensurately, rendering the entire service increasingly uneconomic. Growth in parcels, as physical retailing gives way to online purchases, has so far only partially compensated for the loss of volume in letters.

Under Royal Mail’s so-called “Universal Service Obligation”, the company is by law required to deliver letters six days a week to each and every one of the UK’s 32 million postal addresses, from John o’Groats and the islands beyond to Land’s End.

We might use its services less and less, but surveys repeatedly show that we still overwhelmingly value and indeed treasure this utility and do not want to see it undermined.

One of the reasons the Post Office scandal has resonated is that our attachment to communitarian services of the sort provided by Royal Mail – confusingly, the Post Office and Royal Mail are no longer part of the same organisation, having been separated in advance of the latter’s privatisation – remains as strong as ever.

Call it a nostalgic throwback to the past if you like, but for many, the postman’s daily call remains a lifeline to the outside world. This makes our sense of grievance and injustice all the stronger when things go wrong and the service fails. If you cannot trust the Post Office, who can you trust?

Public sympathy for Royal Mail is plainly not going to be anywhere near as great as it is for the plight of wrongfully convicted sub-postmasters.

Only last November, Royal Mail was fined £5.6 million by Ofcom, the communications regulator, for falling woefully short on required standards of delivery. Over the years, the brand has been progressively devalued by poor service, inflation-busting price increases, and repeated strikes by postal workers.

Yet we still have every right to expect a reliable, universal postal service, and would reasonably think that we had lost advanced economy status if it were to be abandoned, or even substantially curtailed.

The problem for Royal Mail is not just that technology is rendering letter-writing and notification increasingly obsolete, but that unlike rival delivery services – able to cherry pick the most profitable, densely populated catchment areas – it is forced to provide the service universally.

In some respects, the obligation is an economic plus, helping to provide the hugely beneficial resource of nationwide connectivity. This in itself must surely be worth something.

But despite the already eye-popping price of a first class stamp, any universal postal service is bound to be more of a routinely expected public service than a fully commercial endeavour. As volumes shrink, the USO has become a millstone around the company’s neck.

True enough, Royal Mail and its workforce have been slow to modernise. If they have been left behind in a bygone age, it is as much their own fault as the demands of the USO.

Yet you can have all the efficiency gains in the world, and they are not going to keep up with a two-thirds collapse in volume when the workforce of posties has to be kept broadly the same so as to be able to deliver on a daily basis to every household in the country.

In any case, a universal service obligation for the twenty-first century might more usefully be focused on ensuring digital connectivity via full fibre broadband for all than sentimentally maintaining the infrastructures of the past.

Or on ensuring rapid rollout of 5G mobile networks. On both counts, the UK is falling badly behind its Continental peers.

Even so, it is Royal Mail’s USO that seems to command the greater attention. So much so that it gets a special mention in Labour’s growing list of “all things to all men” election pledges. Under Labour, maintaining Royal Mail’s USO would be a policy priority.

As to how this might be done in a financially sustainable way, answer comes there none. With this in mind, Ofcom, the communications regulator, has been examining the case for reform and plans to set out the options in a consultation later this month.

Elsewhere in Europe, the problem has already been widely recognised and at least partially addressed. Other than getting rid of the USO completely, there are essentially just three options – either subsidise it with taxpayers money, or reduce the demands of the obligation, or allow prices to rise precipitously.

The last of these approaches is a strategy of despair that would only drive a further big fall in volume.

In compliance with its dirigiste mindset, France has gone the subsidy route, with annual payments worth more than €500 million a year.

It has also reduced the frequency of delivery by alternating the service between postal areas on a day by day basis. Germany is also in the process of changing to the alternating model. Italy on the other hand has opted for subsidy.

What seems clear is that simply cutting the number of deliveries from six to five days a week won’t hack it. Four years ago this was judged by Ofcom to be sufficient, saving Royal Mail between £125m and £225m a year.

But since then, the volume of letters has continued to collapse, falling another third. Reducing the number of days is again just chasing your tail to oblivion.

With so many other calls on the public purse, I doubt subsidy is an option for Britain either, even under Labour. What is essential, however, is that any adjustment in the USO reflects what people and the economy actually need, not what Royal Mail and its heavily unionised workforce want, which is just the protection of profits and jobs respectively.

But it’s also about Royal Mail rising to the challenge of finding better and more efficient ways of delivering parcels and other services to households so as to substitute for the death of the letter.