Royals have a new vision. Why they trust Matt Quatraro to execute: ‘He cares about people’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Amid changes atop the Kansas City Royals’ baseball operations hierarchy this fall — longtime lieutenant J.J. Picollo succeeded Dayton Moore after 16 years at the helm — there was one overarching and resonating message from Royals CEO and chairman John Sherman.

Sherman declared a need for more data-driven decisions, less sentimentality and a willingness to turn over the roster.

It’s a model that, in light of the current economic realities of Major League Baseball, has done well for small market clubs such as the Tampa Bay Rays and Cleveland Guardians.

That approach also lends itself to a perception of a club as cold, impersonal, calculating, number-oriented and transaction-heavy.

Enter first-year manager Matt Quatraro to the KC equation, positioned as the nerve center of the organization’s vision.

Quatraro and his coaching staff must synthesize and convey the data while also creating an environment that will get the most out of players, particularly young potential-star position players like Bobby Witt Jr., MJ Melendez and Vinnie Pasquantino — and a young crop of pitchers led by Brady Singer, Daniel Lynch, Kris Bubic and Carlos Hernández.

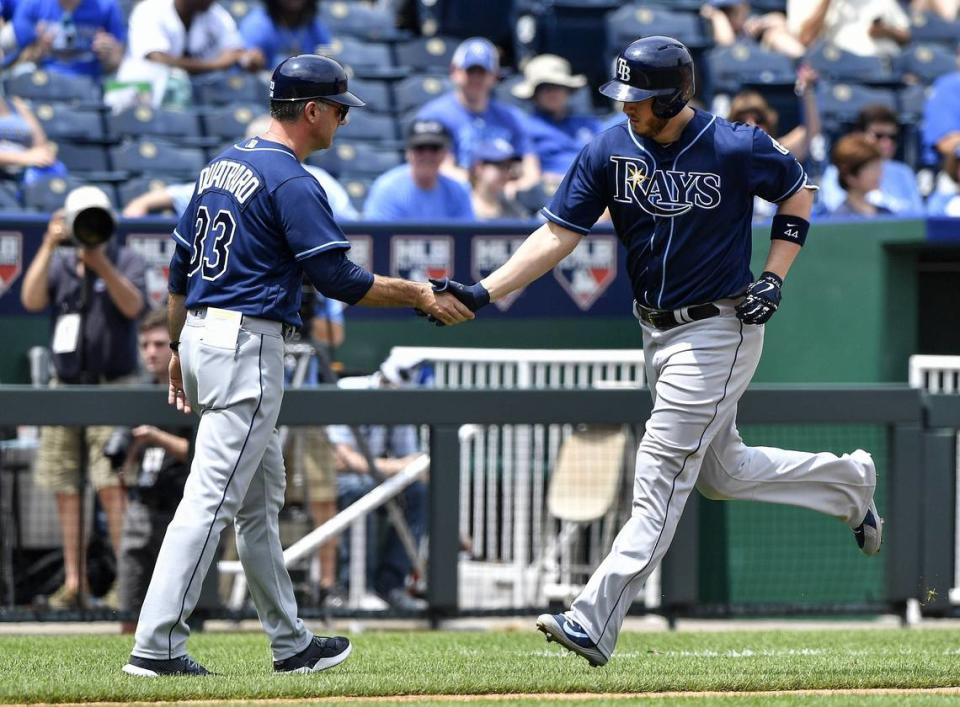

Quatraro, 49, spent his big-league coaching career with the Guardians as an assistant hitting coach and Rays as third base coach and bench coach.

Widely referred to as “Q,” Quatraro is well-versed in numbers, the analytical side of the game and how it’s been implemented to great success on a daily basis with players.

But while Quatraro certainly operates within that world, he’s not of that world.

At his core, he’s a baseball guy who loves competing and winning. The numbers serve as a means to that end.

“I think sometimes the narrative is you’re either an analytics person or a baseball person,” Quatraro said. “And I think that’s far from the truth.”

Simple aims: Compete and win

Born in Albany, N.Y., Quatraro grew up in the hamlet of Selkirk in the town of Bethlehem. His late father was a chemistry teacher and then an assistant principal, while his mother was an elementary school special education teacher.

In that region of the country, the weather often dictated sports participation. Quatraro played multiple sports, including soccer, golf and basketball.

Baseball was never even close to a true year-round pursuit until high school, when he and his teammates hit in a school “closet” during the winter to get ready for the spring season.

Quatraro’s sports focus remained simple. He just wanted to win games with his guys. That’s it.

And it almost worked to his detriment.

“(My high school coaches) were like, ‘You’ve got to go get seen at some of these camps,’” Quatraro said. “I was like, ‘I don’t want to go to camp because that means I’m going to miss my team games.’ You know, legion ball, Connie Mack, Mickey Mantle, those kinds of things.

“One of my coaches convinced me to go to camp at Old Dominion. When I went to that camp, those ended up being the only schools that recruited me — the schools that saw me play at that camp.”

Quatraro’s hesitancy to pursue his own aspirations is a window into his psyche and love affair with baseball.

Competing in those tournaments was dear to Quatraro because “you had to earn your way” by winning. You couldn’t pay an entry fee and guarantee a number of games. You had to win again against really good competition, and he “loved it.”

All these years later, he contends he “never” would’ve gone to the camp if he hadn’t been convinced.

“Because we were winning,” Quatraro said matter-of-factly. “We had a chance to win whatever tournament we were playing in that weekend, or go to the next phase of that. That’s all I thought about or cared about.

“It was a big deal to us, it was a small town.”

Quatraro still stays in contact with some of those same guys he grew up with and played baseball with more than 30 years ago.

Meanwhile, that excursion he begrudgingly took to camp led to Old Dominion recruiting him.

Quatraro became one of the best players in the program’s history. He won the university’s 1996 Male Athlete of the Year as well as the Male Scholar Athlete of the Year award. He went into the university’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2004.

New levels, same approach

Wanting to be there for and win with his teammates served as a driving force throughout Quatraro’s playing career.

Sure, the major leagues were something he aspired to reach. But Quatraro admittedly didn’t have a “great concept” of what it took to make it to the big leagues.

His primary aim in college was to try to help his team get to the College World Series.

“I wanted to get drafted, for sure, but it wasn’t like why I was playing,” Quatraro said. “I was there and kind of taking it as it came. I was fortunate. We had really good teams when I was in college. So it was really focused on winning and wanting to go to Omaha. That’s all we cared about. We never made it. But we got to the regionals three years in a row.”

During his college career, Quatraro played catcher as well as outfield, first base and third base. He was one of only two ODU players to bat .400 for his entire career.

The Rays drafted him in the eighth round of the 1996 MLB Draft, the franchise’s first year selecting players in the amateur draft.

During his transition to pro ball, Quatraro went through the typical adjustments and struggles. He also dealt with injuries.

Then he experienced one of the toughest parts of toiling in the minors. He literally watched other players surpass him in the organization’s pecking order.

“It sucks,” Quatraro said bluntly. “Paul Hoover was one of them. We were roommates. He passed me. That was hard to swallow. It was hard to be objective. You have that belief in yourself, but other people see it differently.

“(You wonder), ‘How do I change this without caring too much about what other people think?’ Then I realized I had deficiencies in my game, otherwise that wouldn’t have been the case.”

Quatraro found himself the odd man out at times, placed on the “Phantom DL” with a fake injury that really just meant the organization wanted to keep him around but didn’t have room for him on the roster.

At one point, there were four other catchers in front of Quatraro, including Sal Fasano, Kevin Brown, Yamid Haad and Hoover. So when he was active, Quatraro played various positions.

Even with that, Quatraro didn’t turn into a malcontent. On the contrary, he took joy in the daily grind, drills, hitting, taking ground balls. And he held onto those big-league dreams.

“That year in Durham, in 2002,” Quatraro recalled, “that was my last year on a regular team, and we won the championship. I played a little bit in the playoffs. So you were still contributing. As delusional as that is, I got into Triple-A playoff games and contributed. I had great teammates and got to celebrate with them, so that was cool.”

Through the eyes of teammates

Let there be no doubt: Quatraro doesn’t hold grudges, at least not for decades.

Hoover and Quatraro were colleagues on the Rays coaching staff, and Quatraro thought highly enough of Hoover to bring him to the Royals as his bench coach.

Hoover actually credits Quatraro for helping him with the position switch from shortstop to catcher when his head was spinning during spring training in 1998.

“I didn’t know what I was doing, but he was a catcher,” Hoover said. “I was working and trying to figure things out, but I had no idea what I was doing. And I didn’t know him from anything other than being in the same locker room.

“He kind of extended himself to me and talked to me about little things about catching, and just guided me along without even knowing. That’s kind of where our relationship started and where our bond started.”

In Hoover’s mind and heart, that explains exactly who Quatraro is.

The two have joked in recent years about the fact that Quatraro helped Hoover pass him, but the two remained friends throughout their time as teammates. They supported each other on and off the field.

“He cares about people,” Hoover said. “He extended himself to me even though I ended up, later, surpassing him. That wasn’t on his radar. He just cares about people. That’s all he was trying to do, help a teammate out.”

Another example, Rocco Baldelli manages the Royals’ AL Central rival Minnesota Twins.

A rare disorder called channelopathy curtailed Baldelli’s major-league career as a member of the Rays in 2005. But in 2002, Baldelli remained a rising star prospect in the Rays farm system (Baseball America’s No. 2 overall prospect in 2003).

Baldelli finished the 2002 season playing in Durham along with Hoover and Quatraro.

Asked about Quatraro, Baldelli smiled and replied, “I love that you asked me.”

“A good friend of mine,” Baldelli continued. “Goes all the way back to being a teammate of mine when I was coming up and I was in Triple-A with the Durham Bulls. The season ended, and you know who drove me home? Matt Quatraro. From Durham to Albany. And my dad picked me up in Albany and we drove back to Rhode Island.

“We’ve known each other a long time. He’s one of my favorite people in the game. Extraordinarily thoughtful guy. He spent a lot of time in the Tampa Bay organization, a little bit in Cleveland. He’s so capable, hardworking. He’s got a lot to offer the Royals. And I think the players are going to eat it up.”

As far as his memory of Quatraro, the hard-nosed catcher/infielder/outfielder/do-whatever-to-keep-playing-at-the-end-of-his-minor-league-career, Baldelli elaborated on Quatraro’s intelligence and demeanor.

“I think you knew he was going to coach at some point,” Baldelli said. “I think that was pretty obvious. I think he always had kind of — he was a pretty wise guy, not a ‘wise guy,’ but there was some wisdom there all along the way.

“Everyone always liked being around him. He’s dry. You’ll get that. He’s going to be a little dry but it’s going to work. He’s always been one of those guys that people have really enjoyed, whether they were staff or players, guys he played with, being around him.”

A coaching education

Quatraro spent 10 seasons in the Rays’ farm system as an instructor, manager and coach starting in 2004.

Then he joined the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) staff as the assistant hitting coaches on Terry Francona’s staff from 2014-2017.

He rejoined the Rays organization as a member of the major-league coaching staff, initially as the third base coach, under manager Kevin Cash in 2018.

As he goes into his first managerial post in the majors, Quatraro contends that he has been influenced more by the last 10 years as a coach than his previous experience as a player and minor-league manager.

The primary takeaway for Quatraro was “how to meet players where they are.”

Even as Quatraro moved up to bench coach, a step removed from the manager, relationships remained his primary focus.

That’s part of the reason people like Blake Butera, manager of the Rays Low-A affiliate, raves about Quatraro.

“This guy is unbelievable,” Butera said. “For example, giving all of our minor league coaches calls throughout the season just to check on things while he’s a bench coach in the big leagues worrying about how to beat the New York Yankees. There obviously were bigger fish for Q to fry, but he puts such an emphasis on creating relationships and really caring about people. You feel it, it’s real.”

Those hard-to-quantify personal touches have become a big part of Quatraro’s evolution as a coach.

His time with Cleveland and Tampa Bay reinforced that its about adapting to what best gets through to each player individually.

“The players are more invested in it than you are,” Quatraro said. “This is their livelihood. They’ve got families. They’ve got all kinds of outside pressures. Understanding what that means to them is a thing I still continue to learn, but that was drastically different than doing it in the minor leagues.”

His time in the majors also made him more conscious of the impact life away from the ballpark has on a player.

For example, Quatraro recalled a time last year with the Rays when a player was scheduled to be in the lineup when his young child went to the hospital the day of the game.

“There’s no question that that’s what they’re going to take care of,” Quatraro said. “We would do the same thing in our job. That player ended up missing a decent amount of time to deal with that. And it definitely hurts the team, but you have to afford them the ability to do that. I think that’s something I probably had no concept of as a minor-league manager or coach.”

Both with Cleveland and Tampa, Quatraro saw those examples play out with players, staff members, even himself when his first son was born; he was a coach and got extra time away from the club.

The lesson?

If you take care of people, you get better performance on the field in return.

How does that manifest? Where do you see that payoff?

“The buy-in, the messaging,” Quatraro said. “I don’t know if you could technically say, ‘Well, he got two hits the next night because you gave him that extra day.’

“Of course, that could have happened anyway. There’s randomness in the game. But they’re certainly going to be in a better state of mind from those decisions than if you just said, ‘I don’t care. You’re back. You’re playing.’”

Taking on a new role

Cash, a former major-league catcher, has won a pair of AL Manager of the Year awards and gone to a World Series in his eight-year tenure with the Rays.

He pointed to Quatraro’s demeanor as something players and observers will appreciate in KC.

“I think with his personality, consistency really sticks out,” Cash said. “The people that I’ve played for, the people that I’ve worked underneath, I’ve learned that consistency is important. They want to see that day in and day out — regardless of the win, the loss, if you can be the same guy — and he was that for the five years we were together.”

Pitcher Ryan Yarbrough signed with the Royals as a free agent this offseason. Prior to that he’d spent his entire major-league career in the Rays organization, five seasons playing for a club with Quatraro on the coaching staff.

“He’s got that really calming presence,” Yarbrough said. “He’s really intelligent, really knows what he’s doing. He’s really personable with the guys. He can really relate to people. I think that’s what you look for. Knowing you’re going to look into the dugout and nothing is going to affect him. He’s not going to ride the wave. He’s going to be really consistent with who he is as a person.”

Quatraro walks into this season aware that he’s taking on a role he’s never held before with more scrutiny and responsibility than he’s ever handled.

He doesn’t plan to take that all on his shoulders as though he were Atlas tasked with holding up the heavens alone.

He plans to delegate and allow his staff members to run their own departments.

“I’ve never been in this seat, so that’s how I envision it because that’s what I’ve seen,” Quatraro said. “Tito is not a micromanager. Cashy is not a micromanager. That doesn’t mean they’re not involved or not aware. I love the discussions, but I couldn’t go out there and coach the pitchers. I don’t know how to teach infield play as well as José (Alguacil) does.

“I played infield. I played outfield. But these guys have been doing this. The only area that I have any of the expertise in is hitting, but I’ve been out of that for five years. And that changes by the minute. I’ve been loosely involved. These guys are the experts in those areas. So for me to go in the cage and be like, ‘No, you’ve got to do it this way,’ that’s not realistic. But we’re going to have tons of discussions.”

“Curiosity” is the commonality that will tie them together as a guiding principle. Ideally, that will lead to discussions built around phrases like: “Have you thought of this?” And they’ll bat things back and forth without ego.

After all, as Quatraro points out, you never truly have control as a manager. The players are the ones on the field.

All he can do is put them in the best spot.

That first moment, when everything directed Quatraro to go one direction and things still went painfully awry, his managerial career will have truly begun.

“I don’t know how I’m going to feel every time that happens, because it happens all the time,” Quatraro said. “I mean, ‘Yup, we should go get (Scott) Barlow in this spot and bring him in because he’s going to mow these guys down.’

“Well, nobody has ever pitched with a 0.00 ERA for the year. He’s going to give up a hit, a home run. I’m going to feel as bad as he does, but I know we did the best we could of putting him in the right spot. At least that’s how I feel right now.”