Rubin: Bob Dylan's first album could change a blind Detroit artist's life

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Stephen Handschu has been blind since birth and poor for about as long as he can remember. One of those things could change in a few weeks, with an unknowing hand from Bob Dylan.

A hard rain’s a-gonna fall, Dylan sang, and this time it could fall in the right place for a 76-year-old who has virtually no eyesight but has the vision to be a sculptor, a firm voice for change and a teacher of self-defense for others who don’t want a disability to mean vulnerability.

Handschu owns the only known master tapes from the recording of Dylan’s first, self-titled album in November 1961: the back-and-forth with a legendary producer, the songs on the record, a few that didn't make it. They’ll be sold online by a New York auction house at 2 p.m. Dec. 14, and if someone offers even the minimum bid, they could be the rising tide that finally lifts Handschu's boat.

He’s trying not to picture how high his fortunes might rise.

“You can’t have been an artist in America your entire life and think, ‘This show is going to change everything,’ “ he says.

Not one show, not one sculpture. But three tapes, nearly thrown away, kept unheard in Handschu’s various closets as he wandered for decades, and finally ready to find a more prosperous home?

Maybe. Even the auction house, Guernsey's, is mystified about the potential pool of bidders and what they’ll offer. But if his ship comes in, he says, others will stand with him at the dock.

He volunteers with Eye Learn Cares, a nonprofit that teaches life skills to blind people in Detroit, and it has been promised a cut. Likewise a sound engineer in suburban Chicago who happened to have a piece of obsolete equipment stashed in a back room when the right customer asked just the right question.

“I’ll do as much as I reasonably can,” Handschu says. “I’ll be more generous if it’s millions, as opposed to a few thousand.”

This year could mark his last Thanksgiving living in a subsidized studio apartment in downtown Detroit where the elevator smells like a garbage chute and hookers were only recently discouraged from conducting business in the laundry room.

Or not. Most things are beyond his price range, many others beyond his control.

“We’ll see,” he says — a phrasing that’s universal, even if eyesight isn’t.

Artworks in the light

Everyone wants to know about his vision, so Handschu speaks of it comfortably — even though, he says with equal ease, "It's one of the least interesting thing about me."

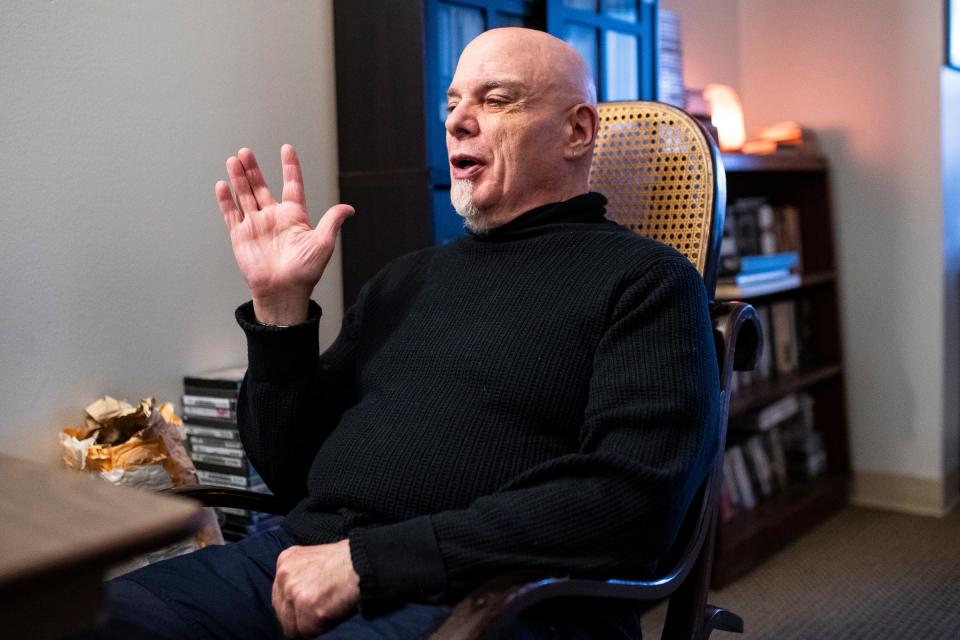

He's a stocky 5-foot-7, bald, a resonant and reassuring speaker with an inch-wide strip of white beard. In his tidy apartment along Woodward Avenue, he often won't think to turn the lights on, but for a visitor he has flipped the switches.

The decor includes three of his sculptures, two of graceful hardwood and metal and one of gypsum cement troweled over wire mesh and steel rod. One of the hardwood pieces is a pair of cupped hands atop a copper plate hammered into an inverted bowl. The other, larger and more evocative, is built around a World War I artillery shell.

Hanging on one wall is a mesmerizing photograph of the late Clarence Baker, lit with flashlights as he stands next to the piano-shaped bar at Baker's Keyboard Lounge.

There's a 6-foot-tall cabinet of CDs, mostly jazz, three dozen alone from Miles Davis. A few shelves of DVDs, including "The Wire" and "The Shield," though he favors old movies because they have more dialogue. A rocking chair.

Leaning against the front door frame, a white cane.

Handschu's right eye never worked for more than light and shadow and it ultimately began to hurt, so a few years back, he found a surgeon who would remove it.

His left, partly hidden behind a drooping lid, offers 20% of the average field of vision and almost none of the strength. He doesn't know the color, which is hazel, though whoever filled out the form for his state identification said black.

Holding his cellphone 2 inches from it, concentrating for 90 seconds or so before the strain becomes pain, he can make out one or two letters at a time.

Growing up in upstate New York, that was enough for the schools to declare him sighted and refuse to teach him Braille. Instead, he says, he became a lab rat, outfitted with contraptions and approaches that checked boxes but left him essentially illiterate.

"I'm not angry at anybody," he says, not even the camp counselors who insisted he try to hit a baseball. But he vividly remembers the frustration, and that's probably a positive; it fuels the part of him that has been active with the National Federation of the Blind, with disability rights campaigns and with people who simply need help to function better in a murky world.

Ultimately, he says, he learned Braille and learned to depend on himself. He found that he could route his creativity from his imagination through his fingertips, no eyesight needed.

He spent one year in college, then interned with a sculptor in Puerto Rico who told him not to go back.

Be an artist, the sculptor said. Go to New York.

Tapes, tasks and travels

Dylan was 20 when he recorded "Bob Dylan" at Columbia Records' Studio A on 7th Avenue. In 1966, five years later and 4 miles away, 19-year-old Handschu rented a place to live and work.

That's where someone whose name he doesn't remember gave him the tapes.

In a simpler era in lower Manhattan, a parade of wayfarers camped briefly in Handschu's studio, urban hobos chasing dreams of their own. One young man, a would-be blues musician, was a janitor at Columbia.

He saw the tapes in a stack of others destined for the trash and was granted permission to rescue them. Old tapes were sometimes erased before they were discarded, and they were in a largely unplayable size and format, but he figured Handschu would appreciate the history.

He was correct.

"Even if they had nothing on them," Handschu says, "they were part of a recording session that changed American music."

The record included only two original songs, along with 11 covers, and it hadn't sold well.

"Dylan had moved on," he says, propelled to stardom with half a dozen subsequent albums featuring his own writing, and Handschu would move on as well.

Priced out of New York, he tried Detroit. Next came Chicago, Florida and Detroit again.

He worked as a union organizer, a carpenter and even a mover, leaving his cane in the truck "so people wouldn't be worried about a blind guy carrying their refrigerator."

In 2007, he was consulting with the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners on audio ballots, a necessity for some disabled voters and a project that made him a regular visitor to a sound engineering shop in suburban Evanston.

The job paid decently, as he recalls, and come mid-December, there could be a long-delayed bonus.

More from Neal Rubin: 'Free Harbaugh' and 'Michigan vs. Everybody' would score better for a true underdog

Words and music

The ballot project was a large and fairly dull operation, says Scott Steinman of Studiomedia Recording, with the best part a new friendship with the consultant.

Then Handschu wondered about an old and problematic stack of tapes parked on a closet shelf, 41 years after they had come his way, and wait a minute — did you say Bob Dylan?

The tapes are a professional-grade half-inch wide, not the standard quarter-inch, and they're on oversized 10½-inch reels. By then, the world had gone digital anyway. But Steinman had an old half-inch machine buried in a back room, and ...

Disappointment. “The rubber parts had turned to goo,” Steinman says.

Fortunately, he knew someone who could refurbish the machine. Unfortunately, it took five or six months.

Finally, he cued up the first tape, connected to giant studio speakers, “and there’s Bob Dylan. There he is. Big as life.”

It was, he says, “breathtaking.”

Dylan, unaccompanied, playing guitar and harmonica. Dylan, unrefined, singing. Dylan, unsophisticated, stumped for answers to routine questions from legendary producer John Hammond, who helped jump-start the careers of Count Basie, Billie Holiday and Bruce Springsteen.

LISTEN: Excerpt of Dylan master tapes, "In My Time of Dying"

Dylan finishes the folk standard "Man of Constant Sorrow," for instance, and Hammond wonders who wrote it.

"I don't know," Dylan says.

"Has it been recorded?" Hammond asks.

"Not that way."

"How has it been recorded?" Hammond responds patiently.

"A different way, I guess."

The tapes come with handwritten notations and two unreleased tracks. The reel numbers end with "D," which suggests there might have been A, B and C copies, but their existence is uncertain and Handschu's tapes would be considered masters nonetheless.

"It's like being in the studio with them," says Steinman, 68.

LISTEN: Excerpt of Dylan master tapes, "Man of Constant Sorrow"

Like Handschu, he won't let himself speculate on what that experience might be worth at auction, or what his slice of the proceeds might be.

Neither will the auctioneer.

Guernsey's gets it

Arlan Ettinger founded Guernsey’s in 1975 as an alternative to the stuffy auctions that offered either grandma’s lamps or Renoir’s paintings.

Other typically atypical items in the Dec. 14 auction include Elvis Presley's sixth grade report card, a note from John F. Kennedy, watercolors by author Henry Miller and a Coney Island carousel horse.

With a focus on pop culture and history, Ettinger's firm has handled Jerry Garcia’s guitars, Rosa Parks’ archive, the Chelsea Hotel’s hardwood doors and Mark McGwire’s 70th home run baseball, that last for $3 million.

Presale estimates, as in real estate, are based on precedent. The problem with the Dylan tapes, he says, is that he can’t find anything similar.

One of Garcia’s guitars went for $1.9 million in 2017, but it can be strummed. Sotheby’s gaveled off a typed, annotated lyric sheet for “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” for $262,000 in 2015, but that could be framed and read.

“Are these recordings historic and important? 100 percent,” says Ettinger, 79. “They gave rise to his career, these tapes. What does that make them worth?”

It’s a rhetorical question.

“All we can do,” says Ettinger, 79, “is get the word out and hope for the best.”

Handschu says he approached other auction houses that either couldn’t give the tapes the push they need, or didn’t know what to do with them. He'd get frustrated or sidetracked, then regroup and try again. A good friend found Ettinger, and for that the friend will get a piece of the proceeds, too.

Guernsey’s has already listed the tapes on two bidding platforms, though it’s unlikely they will generate much action before Dec. 14. The sites insist on a minimum bid and an expected sale price, he says; those are set at $400,000, and $800,000 to $1.2 million.

“In truth,” Ettinger says, “we can and may lower that,” and if no starting bid reaches $400,000 once the festivities begin, “we will drop it until we get a starting bid.”

Volunteering and donating

The owner of the Garcia guitar donated the $1.9 million to a nonprofit, the Southern Poverty Law Center. But he was already rich when he bought it for $800,000.

With Handschu, Ettinger says, “How selfless can you be? It is beyond extraordinary that someone with so little is willing to give his money away to an organization that helps people like him. That’s pretty outstanding.”

Sabrina Rice concurs.

Rice, 51, has a degree in chemical engineering and worked in business operations until 11 years ago, when her right and left retinas permanently detached within three weeks of one another.

She flung herself into her new reality, learned to read Braille and thrive, and founded Eye Learn Cares in Detroit when she realized how many people needed low- or no-cost training in mobility, life skills and self-defense.

Handschu teaches the nonprofit’s martial arts classes. For a favored student — Rice’s husband, retired Detroit police officer Darryl Rice — he crafted a white cane with a carved fist at the top.

Having donated his services to Eye Learn, Handschu plans to follow up with a check. Like everyone else, Rice is trying not to think about how big it might be or how much it will help accomplish.

“Whether it’s $50 or $500,000,” she says, “it’ll be a blessing."

Shaping life his way

Handschu says he has always been selfish, though not in a standard way.

"I did things that were meaningful to me," he explains. "They usually pay you to do what they want you to do."

He's satisfied with the outcome, even if his income stream is a trickle from Social Security and the occasional small job.

He has friends from multiple spheres, two daughters and an ex-wife who likes him enough that they'll have Thanksgiving dinner together. Oh, and there's a girlfriend, a delightful unexpected development, and she'll be there with her children.

"I do not want to come across as this poor blind guy," Handschu says, or as a greedy one. In the ways that have always mattered most, he's doing well enough.

Soon, in more visible ways, he'll be doing better. As Bob Dylan put it, the times, they are a-changin'.

The mystery is how much — and that, he's curious to see.

Neal Rubin wishes one and all a stellar Thanksgiving. Reach him at NARubin@freepress.com.

To subscribe to the Free Press at discount rates, click here.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit artist to auction Bob Dylan's first album master tapes