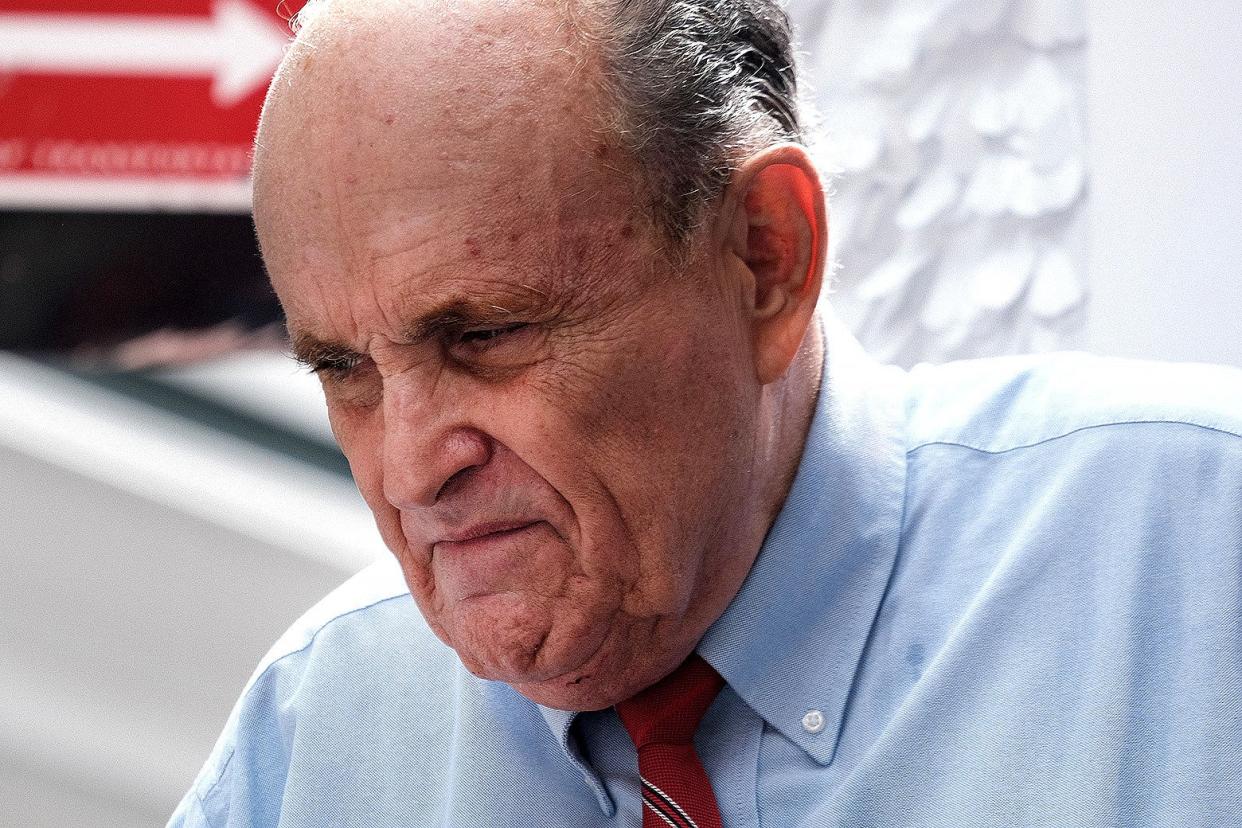

Rudy Giuliani Set the Legal Trap He Has Fallen Into

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Many have noted the irony here: Rudy Giuliani has now been indicted as a co-conspirator under the same law—the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act—that he invoked many times as a federal prosecutor busting Mafia gangs and inside traders on Wall Street in the mid-1980s.

But irony is too mild a tag to capture the predicament in which this man finds himself. Shameful and appalling are other words that come quickly to mind. Another term—more apt still after a moment’s reflection—is bewildering.

More than any other lawyer in America, Giuliani should have known that getting mixed up with Donald Trump—especially in Trump’s plot to overturn the 2020 presidential election—would likely land him in his present state: an indicted felon who, at age 79, may spend the rest of his days in a federal courthouse, then prison.

As U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York, Giuliani didn’t merely cite RICO statutes to take down many criminals; he practically invented the art of doing so. Congress passed the RICO Act in 1970, mainly as a way to go after Mafia kingpins, who had been able to evade indictments as long as they avoided direct involvement in their gangs’ crimes. RICO referred to “predicate crimes”—acts that prosecutors could stitch together as evidence of a corrupt organization and then lasso all of its members as part of a “criminal enterprise.” In other words, it was designed to go after “conspiracy.”

Giuliani and his team were the first prosecutors to figure out how to do this, in a systematic way, in a major felony case—and it was precisely the sort of case that the statute’s drafters had in mind. In the Mafia Commission trial, which lasted from February 1985 until November 1986, the Southern District indicted 11 Mafia figures, including leaders from all of the “five families,” who controlled myriad businesses and municipal services across New York City. Convicted of charges including extortion, labor racketeering, and murder for hire, the leaders were sentenced to between 70 and 100 years in prison.

After shutting down the five families, Giuliani went after white-collar criminals in the financial world, indicting Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken, whose insider trading practices were breathtakingly brazen—and lucrative. Boesky pleaded guilty, turned state’s witness, and served three and a half years in jail. Milken, tried on 98 counts of racketeering and fraud, was fined $600 million and sentenced to 10 years—a penalty reduced to two years after he testified against former colleagues. Donald Trump pardoned Milken in 2020.

The trials of the five families and the Wall Street insiders put Giuliani on the map. He ran for mayor, winning on his second bid in 1993, on the basis of his success as a crime-fighting crusader. The trials also legitimized RICO as a powerful prosecutorial tool against criminals who couldn’t easily be nabbed for their individual acts. (It is significant that Al Capone, the most notorious mobster in pre-RICO days, was indicted and prosecuted on the relatively minor charge of income tax evasion.)

You would think, then, that even a quarter-century later, Giuliani would be especially leery of the many activities and associations that might ensnare him in the vast and deadly tentacles of a RICO prosecution. How did he fall into this trap?

For one thing, the Rudy Giuliani of the Trump era is very different from the Rudy Giuliani of the 1980s and ’90s. I interviewed Mayor Giuliani several times when I was a reporter covering New York for the Boston Globe. He was a liberal Republican back in the days when there were such creatures; no Republican could be mayor of this very liberal city if he weren’t at least somewhat liberal. (See also: John Lindsay and Michael Bloomberg.) Giuliani even endorsed Democratic Gov. Mario Cuomo in his 1994 reelection contest, denouncing the Republican challenger, George Pataki, as “corrupt.” (Pataki won and never forgave Giuliani.)

When terrorists struck the Twin Towers, Giuliani was at a personal low ebb. He had recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer and divorced his wife (an announcement he made on local television), who had kicked him out of Gracie Mansion. After 9/11, he roused himself into action, read Churchill’s memoirs for inspiration, rallied the city to recovery, and was acclaimed as “America’s mayor.”

Absorbing the adulation—and gradually coming to believe his own mythology—Giuliani plotted a course to the White House and was considered a more than plausible candidate. But he flamed out in his 2008 bid for the GOP presidential nomination, winning just one delegate in the primaries after spending $50 million. He lost because—as an advocate of gun control, gay rights, immigration reform, and other social causes—he was too liberal for the party’s base.

After that humiliating campaign, he faced a choice: get out of national Republican politics or tack hard to the right. He chose the latter, emerging as one of Trump’s most fiercely growling attack dogs in the 2016 election against Hillary Clinton (whom he had called “a nice lady” after dropping out of a much-anticipated Senate race against her in 2000).

He also became rich, racking up high fees as a consultant and keynote speaker. In his days as mayor, he was happy—perhaps happiest—eating a hot dog and guzzling a beer in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium. Now he was hanging out in the Hamptons with the sort of people that he had once zealously prosecuted. Even as mayor, Giuliani had formed a tight circle of loyalists who shit-talked his critics in the foulest language and plotted action against them to the extent they could. Sometimes he turned vindictive. Early in his first term as mayor, for example, he spoke at a meeting of Al Sharpton’s supporters. A few of them yelled at Giuliani; he walked out in a huff and never met with Sharpton—or any other Black leader, except the city’s few Black conservatives—ever again. (His weakest and most reprehensible feature, even in his most liberal phase, was a fear and hostility toward Black people.)

This arrogant defensiveness—magnified to a much larger scale, amplified to a much louder volume, and articulated in a more vociferous tone—is what we now see when Giuliani blasts Trump’s presumed enemies (whom he seems to regard as his own enemies as well, so enmeshed has he become with Trump).

In his 2022 book Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor, Andrew Kirtzman reported that the relationship between Giuliani and Trump was close dating back to the days when one was a mayor, working on some of Trump’s real-estate development projects. In the past few years, though, Giuliani has no doubt also seen Trump as his connection to power—the sort of national power he’d once desired but could never attain on his own. He no doubt saw the legal maneuverings he helped concoct to overturn the 2020 elections, and extend Trump’s term in the White House, as the path to preserving his own clutch on power as well.

Along the way, driven by an insatiable desire for wealth and power, Giuliani lost sight of many things from his past—his political values, his personal tastes, and, it seems, his deep understanding that if you hang around with corrupt people, helping them do corrupt things, you can get hammered by his old friend, RICO.