Run, hide, fight: School shooter drills can be traumatic, but do they work?

The 911 call came in minutes before noon: A 13-year-old at Slinger Middle School yelled he had a gun, sending his tiny Wisconsin town into a panic three days after a mass murder at a Texas elementary school.

But teachers and kids were ready – they'd practiced for this nightmare scenario every semester.

Staff turned out lights and locked doors, using devices that latch into the floor. One teacher grabbed a baseball bat. Some kids snatched the golf balls stockpiled in each classroom, ready to throw at an intruder. Parents and guardians flocked as instructed to the parking lot of a bowling alley.

It was a false alarm: The student never had a gun. The 75-minute lockdown ended after police detained the teen, and children reunited with their terrified families.

"The sad part is that our kids have to go through this," said Jason Ford, whose 14-year-old son is a student at Slinger. "They have to be prepared or even think about the worst possible scenario."

The incident left many wondering: Would they have survived a real attack?

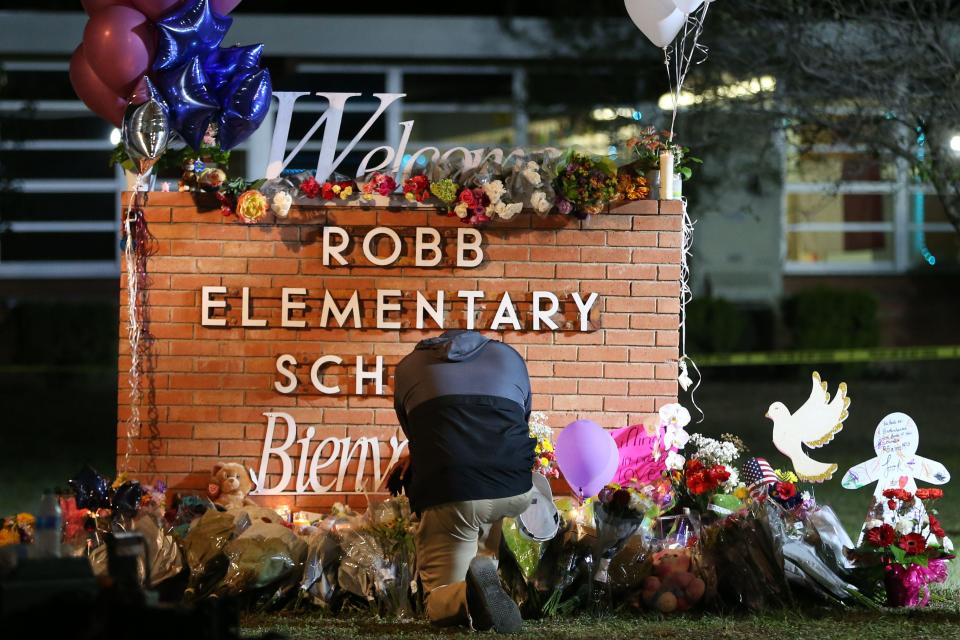

It's a question worrying many Americans as school systems reevaluate their active-shooter response training in the aftermath of the massacre that killed 19 students and two teachers in Uvalde, Texas – a tragedy compounded by law enforcement's decision to remain outside instead of rushing to the rescue.

Related video: Students stage nationwide walkout after Texas shooting

To better understand how students and staff are taught to respond to active-shooter situations, USA TODAY contacted every state and the 25 largest school districts. Active-shooter trainings vary widely, lack oversight and may do more harm than good:

At least 42 states require schools to run some form of drill that could address an active-shooter situation. Although a student in Missouri may never experience an active-shooter drill, students in some Florida counties have them monthly.

Though some people advocate for traditional lockdown approaches, there's a growing movement – and industry – teaching students and staff to make more independent decisions, such as running from or fighting off a gunman.

Drills can have negative mental health impacts for students, teachers and families, but researchers say it’s hard to study whether drills help save lives.

Students or former students – who were probably trained in their school's procedures – were the shooters in three-quarters of the 191 active-shooter incidents from 1970 through Uvalde, according to data from the K-12 School Shooting Database.

Trainings and drills "may make people feel better," said Michael Dorn, executive director of the nonprofit Safe Havens International, a school safety center, but many are "unreliable forms of homeland security theater."

Lock down, run, hide or fight? Training depends on where you go to school.

Amber Aguilar said her two small children are trained to lock down in the event of a shooter at their elementary school in Austin, Texas. After Uvalde, she wonders if kids should be taught more about what to do if an intruder enters the room.

"The survival stories of these young children that were in the classroom is something that none of us would have hoped or thought that we had to teach our children," Aguilar said. "I think all schools should probably reassess their drills based on that."

Lockdown drills became the "industry standard" for preparing for a shooter in the wake of the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999, said Ken Trump, president of consulting firm National School Safety and Security Services.

"They just have us stay in the classroom, turn all the lights off, close all the blinds and have us be quiet in the corner," said Lucas Flory, 16, a student in Colorado.

Federal data indicates most public school students have practiced a lockdown drill, which is used for any threat inside a school building.

The majority of states require at least one drill annually that may be used to prepare for an active-shooter situation, and states use a variety of names to describe these drills. Many make principals file a statement certifying drills were conducted and require school boards to meet periodically to review requirements.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Active-shooter drills, as some states and districts call them, are often less standardized than lockdowns, though many include a lockdown component. Some are unannounced. Some require guardian notification. Drills that involve simulations – with the sound of gunfire or staff acting out roles – have become the most controversial.

Decisions about what type of training to teach typically fall to the district. School personnel and students may receive different training from different instructors, such as private consultants or law enforcement.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Most schools focus on lockdowns, Trump said, but in the past five to 10 years, there's been a movement, largely driven by current or former law enforcement officers, to teach "options-based" models.

The U.S. Department of Education recommended schools adopt such models after the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, when a gunman killed 20 children and six adults in Newtown, Connecticut. The department said it provides various training resources to schools, including on the "Run. Hide. Fight." model.

The approach was initially developed by the Houston mayor's office in 2012 for adults in the workplace. It "empowers individuals who find themselves in an active-shooter incident to have a voice in their survival," the FBI said.

Annika Tekumulla was a junior when her high school in Port Huron, Michigan, introduced "Run. Hide. Fight." She said her teacher instructed students to grab scissors if an intruder ever entered. "We were expected to fight for our lives in the classroom," said Tekumulla, 19.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Another increasingly popular model is "ALICE" Training, which stands for alert, lockdown, inform, counter and evacuate.

"If the active shooter is in the east wing cafeteria, and I am in the west wing gymnasium – why would I, under a single-option response protocol or code, lockdown or lockout when I could escape and leave the scene to get to the reunification point?" said JP Guilbault, CEO of Navigate360, an emergency management company that teaches the training.

The Wisconsin middle school that experienced the scare last month uses the ALICE approach. Though the drills focus on lockdowns, students are told to "ready themselves," District Superintendent Daren Sievers said. "Don’t just sit back and be a passive sitting duck."

Companies such as Navigate360, that charge schools for trainings, are part of what Trump calls a "cottage industry of security, hardware and product vendors." Gun control advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety estimated the school safety business – which includes the "active-shooter drill industry" – is worth $2.7 billion.

Parents, and even administrators who bring trainers onto campus, often assume a "higher authority" has vetted the curriculum, but that's rarely the case, said Kristina Anderson Froling, who survived a shooting in 2007 at Virginia Tech and runs the Koshka Foundation for Safe Schools.

"There are some for-profit companies that have tried to market themselves heavily and have been successful in gaining access to schools," she said.

Students at Great Crossing High School in Kentucky were told in ALICE training to run, arm themselves with pencils or use a chair to break a window, said Rox Lockard, 18.

"I prefer the running away method because it seems to be a little bit more efficient," Lockard said. "Especially with how rifles are bigger now and they can bust through doors, so the point of hiding in the classroom has become like – there's no reason anymore."

In Uvalde, schools use a broader framework known as Standard Response Protocol for an array of crises, according to the district's website. Texas recommended SRP after a high school shooting in 2018 in Santa Fe, where 10 people died.

The "all-hazards approach" gives schools a common language and focuses on five commands – hold, secure, lockdown, evacuate and shelter, said John-Michael Keyes, who helped develop the model in 2009 after his daughter was fatally shot at Platte Canyon High School in Colorado.

Schools often use SRP as a foundation for building out safety plans, he said. Last year, the foundation added guidance for adults to "prepare to evade or defend" in the event of a lockdown, Keyes said.

Susan Riseling, former police chief for the University of Wisconsin, Madison, noted an 11-year-old girl in Uvalde smeared her murdered friend's blood on herself to play dead. "She was processing to hide in plain view, to decoy herself. And it worked, as wretchedly tragic as that is," Riseling said.

Do drills save lives?

Just having thought about an intruder can help students prepare, but it's unclear whether drills save lives, said Sarah Burd-Sharps, senior director of research at Everytown.

Locking doors works, according to Jaclyn Schildkraut, an associate professor of criminal justice at the State University of New York, Oswego, and Amanda Nickerson, director of the Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse Prevention at the University of Buffalo. They are co-authors of an upcoming book, "Lockdown Drills."

"The perpetrators typically do not have time to defeat the door locks and instead seek individuals who are out in open areas," Schildkraut said.

Before Uvalde, she said, there were three school shootings since Columbine in which someone was fatally shot behind a locked door: in 2005 in Red Lake, Minnesota; in 2006 in Bailey, Colorado; and in 2018 in Parkland, Florida.

In the Parkland shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, a former student fired through the windows and doors of three locked classrooms, where six of the 17 victims were fatally shot, Schildkraut said.

"While there tends to be a focus on the rooms where students were killed, there needs to be an accounting for all of the other rooms in the school building where students do lock down and are physically unharmed," she said.

IS MORE POLICE THE ANSWER? Why research shows that won't help

THEY SURVIVED SCHOOL SHOOTINGS: Now their own kids are in classrooms.

Some school shooting survivors credit training with saving their lives, including students who survived an attack last fall at Oxford High School in Michigan, where four students were killed.

"It's part of school protocol to barricade, so we all knew, barricade, barricade down," Abbey Hodder, 15, said at the time.

Running or fighting saved lives in shootings when locking down wasn’t possible, even when students and staff did not receive that training.

A handful of Sandy Hook students in one of the classrooms where the shootings happened escaped by running when the gunman stopped to reload, Schildkraut said. The gunman entered their classroom before the teacher could lock the door, she said.

In a shooting in 2019 at STEM School in Highlands Ranch, Colorado, students who fought back "potentially" saved lives, she said. When one of the two shooters pulled out a gun in class, another student attacked him and was fatally shot. Two others disarmed the shooter. The school uses SRP, Schildkraut said.

"This outcome is likely more due to the human tendency to resort to fight, flight or freeze," Schildkraut said.

In the 191 active shooter incidents at K-12 schools from 1970 through Uvalde, there were at least 27 in which a shooter was subdued by students, staff or other civilians, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database.

Several researchers and consultants said they were skeptical of approaches that teach students and staff to run, hide or fight.

Encouraging students to run from a shooter instead of locking down could create a "target-rich environment," Trump said. He noted some schools say they use one model on paper but practice another, which creates confusion and liability risks.

Because it's "nearly impossible" to study the direct impacts of drills on safety, most researchers opt to observe compliance with emergency procedures, Burd-Sharps said.

Dorn said his nonprofit has tested numerous response models at thousands of schools in 45 states, including SRP, ALICE and "Run. Hide. Fight."

In tests of staff trained in those models, most employees fail to implement lifesaving actions and often struggle to "fit the situation they’re posed with to the format," he said. Many staffers trained to fight back attempted to disarm someone in situations "where it would clearly be more dangerous to do so," he said.

Many types of active-shooter drills "leave people with a false sense of security," Dorn said.

FOUR YEARS AFTER PARKLAND: Gunfire on school grounds reaches troubling peaks

FACT CHECK: What's true and what's false about the mass school shooting in Uvalde, Texas

'Scary, realistic drills can have detrimental effects'

Though it's hard to study whether certain methods protected students from danger, research has shown "scary, realistic drills can have detrimental effects," said Amanda Klinger, director of operations for the Educator's School Safety Network.

Child psychologists, parents, teachers and others have long raised concerns about how drills affect school communities, noting they're associated with depression, stress, anxiety and physiological problems.

Tekumulla, the former Michigan student, said most people don't understand "how mentally draining it is to go through those drills, knowing that it could be real any time."

After the scare at Slinger Middle School last month, 30 students "shaken by the intensity of the lockdown" needed counseling when they returned the week after the incident, and five went home, said Sievers, the superintendent.

Brennan Cruser, a former elementary school teacher in the Austin Independent School District, said her students – ages 6, 7 and 8 – were anxious about lockdowns and asked if the drills were real, saying, "We're hiding in case someone comes in with a gun."

"We want to focus on their education. We don't want to have to stop and spend the time" on lockdown drills, Cruser said, lamenting that educators are responsible for keeping children alive.

Lockard, the former Kentucky student, said drills used to be traumatic, but the recent graduate became "overexposed" and "blase" about the dangers.

"It could happen to us at any time. There's nothing we can do about it," Lockard said.

The psychological impact of a drill depends on how it's conducted, many said. Schools can teach kids what to do without causing trauma by conducting developmentally appropriate drills using guidelines from groups like the National Association of School Psychologists, Schildkraut said.

"The most frightening experience is when my school forgets to tell us that there's a drill," said Peren Tiemann, 17, an Oregon student who volunteers with Everytown to advocate for trauma-informed training in schools.

In 2019, an ALICE training at a middle school in Ohio left several preteens bruised after a principal posing as a shooter sounded an air horn and some students, confused as to how to evacuate, fell to the ground.

That same year, elementary school teachers in northern Indiana reported being bruised and bloodied after they were shot with airsoft guns "execution-style" during a drill. Eight teachers sued the sheriff’s department that conducted the training.

SCHOOL SHOOTINGS: More kids die from gunfire outside school

As more people speak out about the harms of active-shooter simulations, some states and districts are restricting the practice. In March, Washington state banned drills that include simulations or reenactments.

"There’s a place for drills, but they can’t be this kind of simulation of an actual shooting," said Randi Weingarten, head of the American Federation of Teachers. "Because that is really, really traumatizing."

Changes after Uvalde: 'How far do we go?'

States and school districts reviewed requirements for active-shooter response training in the wake of the Uvalde shooting, and several announced funding for measures.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott revealed plans to ask education officials to conduct "unannounced, random intruder detection audits on school districts" to find security weaknesses, among other actions.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law requiring the state to develop rules for emergency drills, removing authority from districts. The measure mandates that law enforcement be present for active-shooter drills and that school personnel and safety officers receive training in mental health and crisis intervention.

Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee directed state agencies to provide additional guidance to districts on best practices for enhancing building security against an intruder and to increase periodic audits of security assessments and safety plans.

Iowa plans to spend $100 million of federal funding to conduct vulnerability assessments on schools, provide active-shooter training, develop ways to report and monitor threats and more.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine signed a law allowing school personnel to carry firearms in classrooms this fall after 24 hours of training.

Federal lawmakers are considering legislation that could include expanded background checks for 18- to 21-year-old buyers, grants for states to implement "red flag" laws that would make it easier for authorities to confiscate weapons from people who might be dangerous, and funding for school safety resources and school and community mental health resources, among other proposals.

"Schools should be focusing on ways to prevent gunfire on school grounds before it happens," Burd-Sharps said.

In Wisconsin, Ford – the father of the eighth grader at Slinger – said many kids struggle to sleep at night, weeks since the scare. His son, who sat beside him as he spoke with USA TODAY, did not want to talk about what he experienced that day.

Ford said he didn't know his son was taught to grab golf balls and throw them at an intruder. He doesn't like the idea of teaching kids to fight back, but he wants to make sure they learn what they need to stay alive.

"How far do we go," Ford said, "is always the question."

More from USA TODAY

The calls for gun reform follow every school shooting: Here's what they've led to

For 79 minutes, police failed to act as children died at Uvalde school

Before Texas shooting, Uvalde was a place for families, friendship

From Australia to the UK, here's how other countries have responded to mass shootings

Contributing: Romina Ruiz-Goiriena, Ashley Williams, Chris Kenning, Erin Mansfield, Trevor Hughes, Javier Zarracina and Doug Caruso, USA TODAY; Eve Sampson, Detroit Free Press; Molly Bohannon, The (Fort Collins) Coloradoan; Arika Herron, Indianapolis Star; Michael Trautmann and Olivia Krauth, Louisville Courier Journal; AnnMarie Hilton, The (Appleton) Post-Crescent; Jonathan Horwitz, The (Palm Springs) Desert Sun; Isaiah Murtaugh, Ventura County Star

Grace Hauck, Chris Quintana and Alia Wong report for USA TODAY. Megan Menchaca reports for the Austin American-Statesman; Rory Linnane for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel; and Jason Delgado for USA TODAY Network - Florida.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: School shootings: Are active-shooter drills doing more harm than good?