Rural rape victims in Tennessee face obstacles for exams. These nurses hope to change that

As recent as 2018, rape survivors in much of Middle Tennessee had to travel to Nashville General Hospital as the only location where specially trained nurses could perform forensic sexual assault exams.

Katrina Brown, who at the time was an emergency room nurse at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said the lack of access was frustrating and discouraging for the victims, who sometimes traveled hours from rural areas and were required to be escorted to the hospital in a police car.

Recognizing the problem, city leaders pushed to expand Nashville’s Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) program, and today, the landscape looks much different, Brown said.

Nashville now has several locations, including Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where victims can receive an exam from a SANE-trained nurse.

Still, for more rural areas outside of Nashville, victims still face hurdles, said Brown, a nurse examiner who now heads Vanderbilt's SANE program.

But there are efforts to change that and expand access in rural areas — particularly near Columbia, Pulaski in Middle Tennessee and the rural areas surrounding Shelby County.

Fueled by a nearly $500,000 federal grant last fall, Vanderbilt is now expanding SANE training for registered nurses across Middle Tennessee, which Brown said will greatly improve access for rural and underserved communities.

“It’s a step in the right direction, but there’s still so much more we can do,” she said.

While some victims have more access in rural areas, many still must travel to larger towns, Brown said, adding that Tennessee lags behind other states in support and resources.

And despite efforts to expand access to sexual assault exams, Tennessee continues to face backlogs in rape kit processing times, though the state has made gains over the past year.

In another area of concern, nurse examiners and advocates say they’ve seen a growing number of victims who believe they were drugged while out at bars and nightclubs before being sexually assaulted.

Advocates said SANE-trained nurses can be better equipped to deal with victims in these types of situations and can help with resources as they push for greater awareness.

A critical need for trained nurses

SANE is a nationwide program that started in Memphis in 1976 out of concern that rape survivors were not receiving the same standard of care compared to other victims in the emergency room.

The program has picked up steam in cities across the country in recent years as awareness grows.

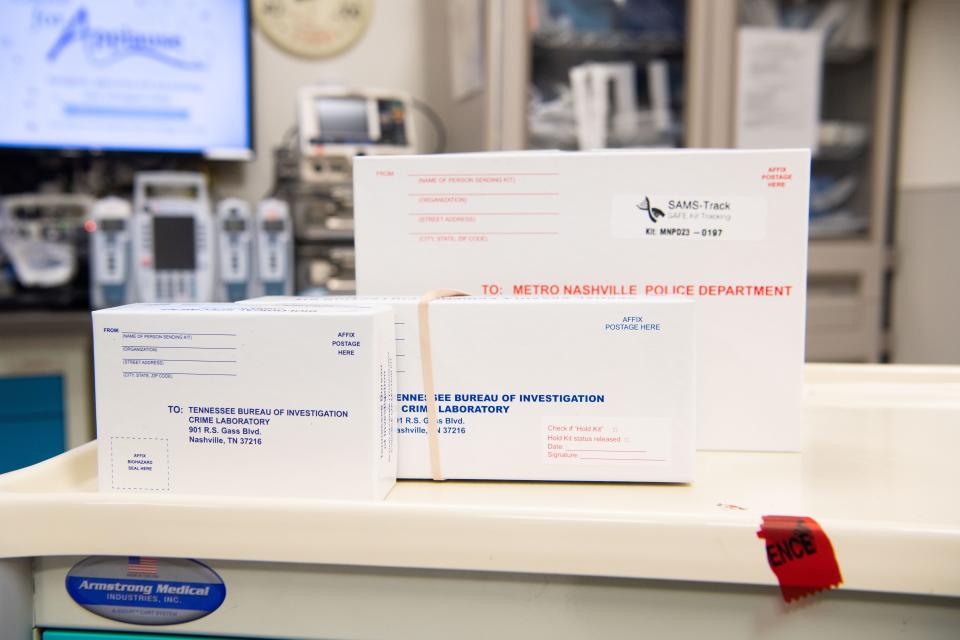

Under the program, registered nurses receive specialized training on how to conduct a forensic exam, also known as a “rape kit,” with 40 hours of classroom training, 40 hours of clinical work and a special focus on trauma-informed care.

Nurses don't have to be SANE trained to conduct a rape kit exam, but advocates said SANE-trained nurses are better equipped to deal with such cases, since many emergency room nurses don’t have experience in forensic exams and are often juggling multiple patients.

“When we get called in to take care of that patient, our focus is only on that patient,” Brown said.

It can also help put more perpetrators behind bars.

A 2008 study funded by the National Institute of Justice found that cases with rape kits conducted by SANE-trainied nurses were more likely to move through the justice system due to the higher quality of evidence collection.

Meredith Boggs, one of about 45 SANE-trained nurses in the Vanderbilt program, said the exam process, which can take between four to eight hours, can be physically and emotionally intense.

Boggs, a Nashville native, signed up for the training after the program launched at Vanderbilt in 2018.

“There were no real services before, so this has been a passion for us,” she said. "I wanted to help my city."

Expanding SANE in Tennessee

With the federal grant, Vanderbilt is planning to train 90 SANE providers, expand access in three rural clinics and fund training for a clinic specializing in LGBTQ+ health.

Brown said it comes at a critical time.

Last year, the SANE program at Vanderbilt saw 141 victims, up from 84 in 2022 and about 70 in 2021. Brown said she believes the increase is due to word of mouth as victims search for care.

Other medical centers in rural areas are also taking steps.

Last year, Center of Hope in Columbia opened a Safe Clinic to expand access for sexual assault victims, and another program is in the works in Pulaski through Southern Tennessee Regional Health System.

Center of Hope Director Cindy Sims said victims previously had to drive over an hour to Nashville for a SANE exam.

“We want them to know that they matter, and we’re doing what we can to take care of them,” she said.

In Memphis, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center won a $1.5 million grant in 2021 to expand SANE programs in West Tennessee.

They have since trained more than 70 nurses, said Dr. Andrea Sebastian, who heads the grant program. Before the expansion, Shelby County’s rape crisis center, the only location where victims can get a rape kit exam, was significantly understaffed, she said.

Sims said the additional funding can help victims in Memphis, as well as rural areas expanding into Arkansas and Mississippi.

“It’s been a need in our area for a long time,” she said.

While Tennessee as a whole has improved in recent years, Brown said other states, like Wisconsin, California and Texas, are further along with statewide SANE coordinators and guidelines for forensic exams.

“There are a lot of resources in other states that Tennessee doesn’t have yet,” she said. “It’s still fragmented without much state guidance.”

Rape kit testing delays and a rise in date rape drugs

While rape kits are becoming more accessible, the state continues to see delays in rape kit testing.

Tennessee in 2022 faced major backlash for its lag in rape kit testing following the high-profile killing of Memphis jogger Eliza Fletcher. The suspect in the case was linked to a previous rape kit that sat in a lab untested for nearly a year.

The state has since improved its turnaround with an average processing time of about 18 weeks in November, down from more than 45 weeks in August 2022. But it still falls short of the goal of eight to 12 weeks, which the state hopes to soon reach.

In another challenge for sexual assault survivors, advocates say they've seen a rise in the number victims who believe they were drugged while out at bars in Nashville and Middle Tennessee.

Of 180 victims who received sexual assault exams at the Nashville Sexual Assault Center between January and August of this year, nearly 25% said they believed they were drugged, a Tennessean report in October found.

Brown said she has also seen an increase in reported cases at the Vanderbilt center.

While SANE nurses can test for some common date rape drugs, the process is challenging as patients often fall outside of the timeframe where the drugs would be detected.

Brown said hospitals should have a more uniform protocol for drug testing as it can vary widely.

In the meantime, the Sexual Assault Center has a Safe Bar program, which works with local bars and restaurants to educate staff on their role in preventing sexual violence.

The program previously struggled to get more bars to participate, with only about a dozen in Nashville and only one — the Whiskey Bent Saloon — on Lower Broadway.

But last fall, the program got an extra $75,000 in funding with support from the Nashville Metro Council Women's Caucus, and about dozen new bars have since signed up for training, said Sexual Assault Center President Rachel Freeman.

“There seems to be an increased and continued energy for this, so it’s very exciting,” she said. “We want to get the word out and get more bars trained.”

Reach Kelly Puente at kpuente@tennessean.com.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Tennessee sexual assault: New grant money helps rural victims