A rush for COVID-19 shots in Utah? Why a county health department filled vaccine appointments fast

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Earlier this week, the Salt Lake County Health Department was so overwhelmed with calls for appointments to get the newly arrived COVID-19 vaccine that people were waiting on hold for up to 45 minutes.

“That tells me that there was a lot of interest,” Nicholas Rupp, county health department spokesman, said Wednesday, the first day the shots were available at clinics in Salt Lake City, South Salt Lake, Sandy, West Jordan and West Valley City.

Monday’s rush for the 570 vaccine appointments available weekly was the result of pent-up demand for the updated vaccine, he said. Since then, call volume has slowed enough that the wait time for callers is down to about eight minutes.

The vaccine was approved by the federal government in mid-September for everyone 6 months and older but now that it has been commercialized, distribution and other issues have made it tough to find shots in Utah and around the country.

Related

Why getting the new COVID-19 booster shot is being called ‘frustrating’

Here’s what the federal government is telling insurers about covering the cost of COVID-19 shots

“There was a group of people that was very eager and they all called the moment they could,” Rupp said. “We have now taken care of those folks and other people who are interested are kind of trickling in now.”

The Utahns who took all of the county’s available vaccine appointments through early next week, he said, are “a wide spectrum, a diverse group of people. Men, women, older, younger. We had a few calling to have their children vaccinated.”

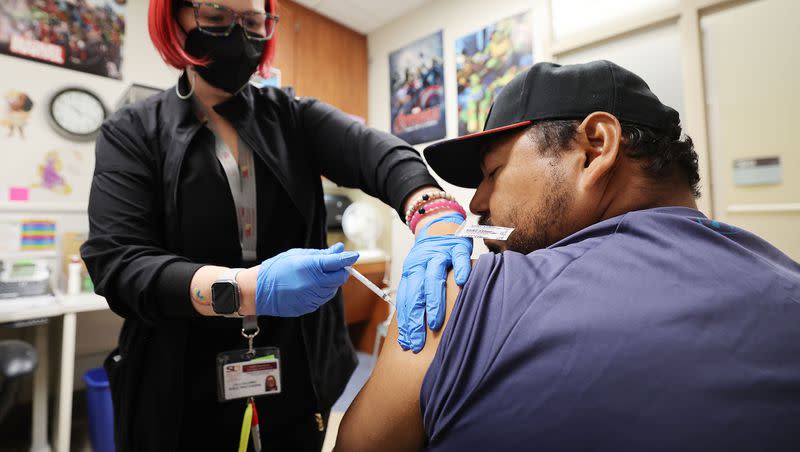

Angie Gonzales received a COVID-19 shot on Monday at the Salt Lake City Public Health Center about a year after the last time she was vaccinated against the virus, with last fall’s booster dose.

“It was just time for a new shot,” said Gonzales, who works at another health care clinic and has a 2-year-old son. She described the COVID-19 vaccine as “just like every other shot, you know? Every season, you’re going to have to get it, no matter what.”

Because the federal government intends for the COVID-19 vaccine to be updated each year, it’s expected to be seen as similar to an annual flu shot rather than a booster to the initial series of shots that came out during the first year of the pandemic.

Still, some are still referring to the new COVID-19 vaccine as a booster dose, even though the updated shots target a single version of the virus that was circulating earlier this year, XBB.1.5, also known as Kraken, but not the original strain.

It’s different from last year’s booster shot, considered a bivalent vaccine because it went after a pair of omicron variants as well as the original strain of COVID-19 from the first vaccines.

Related

Here’s who the CDC says may need more than one dose of the new COVID-19 vaccine

What you need to know about the timing of COVID-19, flu shots this year

Ann M. Sheehy, Ph.D., an immunologist from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, recently told MedPage Today that’s why she’s not using “boosters” to describe the new monovalent COVID-19 shots.

“It’s a new vaccine, and I think people are making a concerted effort to call it the ‘2023-24 COVID vaccine,’ because ‘booster’ kind of implies it’s the same as what it was before,” she said.

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health explains it this way in a Q&A with Andy Pekosz, a molecular microbiology and immunology professor, about what people need to know about the new vaccine:

“Is the new vaccine considered a ‘booster’?

The FDA has shifted from calling this a booster to calling it an updated COVID vaccine. The change in wording reflects that we’ve begun treating COVID like we treat influenza, with annual vaccination. We encourage people to get their ‘annual flu shot’ not a ‘flu booster.’ Calling it an updated COVID vaccine also reflects that we’re not just boosting existing immunity from previous vaccination; rather, the vaccine builds a new immune response to variants that are currently circulating.

It’s likely we’ll still see it referred to as a booster in some instances, but it’s all the same shot.”

Rich Lakin, immunization director for the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, doesn’t care how people refer to the shots as long as they look at getting them. Fewer than 16% of Utahns received last year’s booster shot, slightly less than the national average.

“You can call it whatever you want,” Lakin said. “It’s the monovalent COVID vaccine for fall.”