Russell Brand allegations spark reckoning about the U.K.’s toxic ‘noughties’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

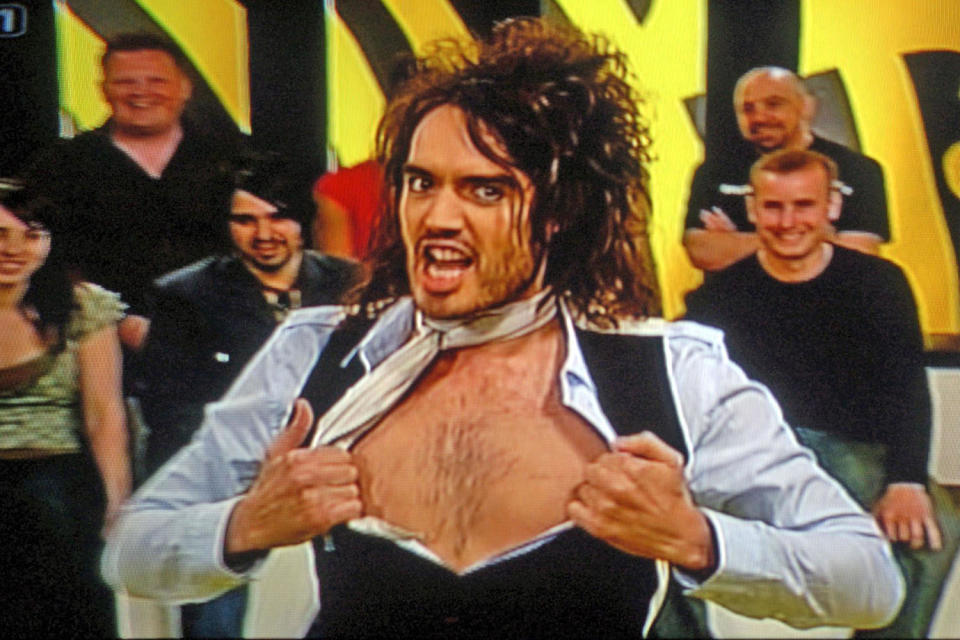

LONDON — The allegations of rape, sexual assault and grooming against Russell Brand have provoked sudden soul-searching in the United Kingdom.

While Brand denies the allegations, saying all of his sexual encounters were consensual, few can reject what was broadcast to millions and plastered across front pages: the toxic and violently misogynist media culture of the 2000s in which Brand was a peacocking protagonist.

And so it’s not just Brand’s career or his former employers that are facing new scrutiny, but the ’00s as a whole, with Britain confronting the reality that this ugliness may lurk much closer to the surface of public life than many realized or admitted.

In recent days much of the revulsion has come from viewers and readers, often with themselves, at being reminded of just how extreme the dominant tenor of entertainment was in the country not so long ago.

“It’s a real culture shock — a lot of things that felt normal at the time feel very abnormal now,” said Sarah Ditum, a newspaper columnist and author of “Toxic: Women, Fame and the Noughties,” which will be published in the United States in January. It was only when she started researching her book two years ago that she “realized how alien that time feels.”

The “noughties” is the British name for the ’00s, also known as the aughts in the U.S. It was a time when, in 2006, Brand joked onstage about enjoying oral sex violent enough to make a woman’s mascara run. A year later he and fellow comedian and friend Noel Fielding riffed about rape during an end-of-year comedy special. And in 2010 British actor Danny Dyer suggested in his “agony uncle” column that a jilted man should “cut his ex’s face, then no one will want her.”

The bounds of acceptability extended to “Harry Potter” star Emma Watson leaving her 18th birthday dinner to find paparazzi lying on the sidewalk to capture upskirt photographs. Singer Charlotte Church had her 16th birthday marked by influential radio DJ Chris Moyles offering on air to “lead her through the forest of sexuality.” And the nation’s top comedy show, “Little Britain,” was replete with blackface and jokes about LGBTQ people and people with disabilities. The show’s stars, David Walliams and Matt Lucas, have apologized.

None of this appears to have harmed the careers of those involved. Today, Fielding presents the internationally beloved “Great British Baking Show.” Moyles has an eponymous program on Radio X. And Dyer was until recently a leading star in Britain’s iconic soap opera “EastEnders.” NBC News has contacted Fielding’s and Moyles’ agents for comment. Dyer wrote in his autobiography that he regretted his “tasteless joke,” saying he never thought the magazine would publish it.

Overt misogyny existed in the ’90s and, of course, before. But what made the ’00s unique was its particular tone of cruelty and “nihilism,” according to Ditum. The so-called lad mags launched in the previous decade had featured scantily clad women, but also quality factual journalism and humor.

What changed? The nascent internet, which blasted “a firehose of uncensored, unmoderated content into people’s lives,” she said, from illegal downloads of music and films to extreme, gonzo-style pornography and revenge porn.

Then came social media, unleashing “a turbocharged version of the media and tabloid sexism we were already used to online,” said Laura Bates, author of “Men Who Hate Women” and founder in 2012 of the Everyday Sexism Project.

Platforms like Facebook and Twitter, launched in 2004 and 2006, “enabled everyday women, not just celebrities, to be targeted with the same slut shaming, body image pressure, objectification and sexual harassment that we’d seen flourish offline in the ’90s,” she said.

A version of all this was happening in the U.S., of course, where stars like Britney Spears were ogled as teenagers before being harangued and destroyed by those same forces. In fact, Ditum attributes some of the decade’s cultural cruelty to America’s defining event: 9/11.

“Because so much of the culture industries are based in Manhattan, 9/11 had a really direct, traumatizing effect,” she said. “You have this huge cataclysmic event that no one is emotionally equipped to deal with” and “it feeds into this really apocalyptic, end-of-the-world feeling in the gossip culture.”

Piers Morgan, then editor of The Mirror newspaper, was quoted in The Guardian four months later saying the attacks had “concentrated my mind and made me realise” the media didn’t have to “suck up” to celebrities anymore. It “empowered us to put celebrities back in their box.”

In practice, Ditum said, what ensued was less an era of legitimate scrutiny and more a “nihilistic celebration of destruction” in the media, one where the feeling was: “The world has burned, and people wanted to see individual women burn within that.”

Britain has always had its own particular brand of risque humor, often exporting it to the States, where stars like Brand, who had a brief stint in Hollywood movies, shocked its traditionally more puritanical audiences.

“British comedy has always been bawdy, raunchy and winking,” said Wynter Mitchell-Rohrbaugh, a cultural commentator and podcaster based in Los Angeles. “The audience takes it in, they don’t think too much of it, but then when you get into real-life consequences, real-life allegations,” such as those leveled at Brand, “it pivots and changes things a lot.”

Brand was endorsed not only by broadcasters and their audiences but leading politicians keen to cash in on his cultural capital. In 2015, then opposition Labour leader Ed Miliband interviewed Brand as part of his election campaign, something he said this week he regrets.

Brand’s former employers, the BBC and Channel 4, pledged to investigate their processes and have pulled some of his work. (Channel 4 commissioned some of Brand’s former shows before airing last weekend’s exposé against him.)

Tim Davie, BBC director-general, said it was investigating allegations by Brand’s then-16-year-old girlfriend that a company car collected her from school and took her to the star’s house.

“This industry has definitely faced significant issues with regard to a deep power imbalance in certain places, between so-called talent, presenters, and others working on shows,” Davie told a Q&A with staff that was released by the organization’s press office.

But as much as audiences, broadcasters and celebrities themselves profess to have moved past those bad old days, many within the industry roll their eyes at the idea that things have changed substantively.

“We know the entertainment industry is absolutely rife, and within that the comedy industry is the least regulated,” said Stevie Martin, a comedian who has participated in WhatsApp groups where women warn each other of industry predators.

“There are so few structures” to protect people, she added, “And many people involved in those structures have obviously looked the other way.”

While Brand’s overt style may not wash now, Martin and others say that the same alleged activity is just better hidden today. It’s more common to hear about men “who go out of their way to appear feminist” but then act inappropriately in private, she said, “and that to me is more terrifying.”

And even if there has been a softening of the cultural rhetoric, there has been little change when it comes to metrics such as rape conviction rates in Britain, with charges brought in less than 2% of reported cases, according to the charity Rape Crisis England & Wales.

“We continue to like to cling as a society to the notion that things have changed and are constantly getting better,” Bates said. But “I think we have a lot of the same problems in 2023; we just struggle to recognize them when they are under our noses.”

She added that “it is baffling to see so many people talking about how normalized sexism was in the media in the 2000s as if this is now a different era.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com