Russia’s collapse has handed China a once-in-a-millennium opportunity to secure domination

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

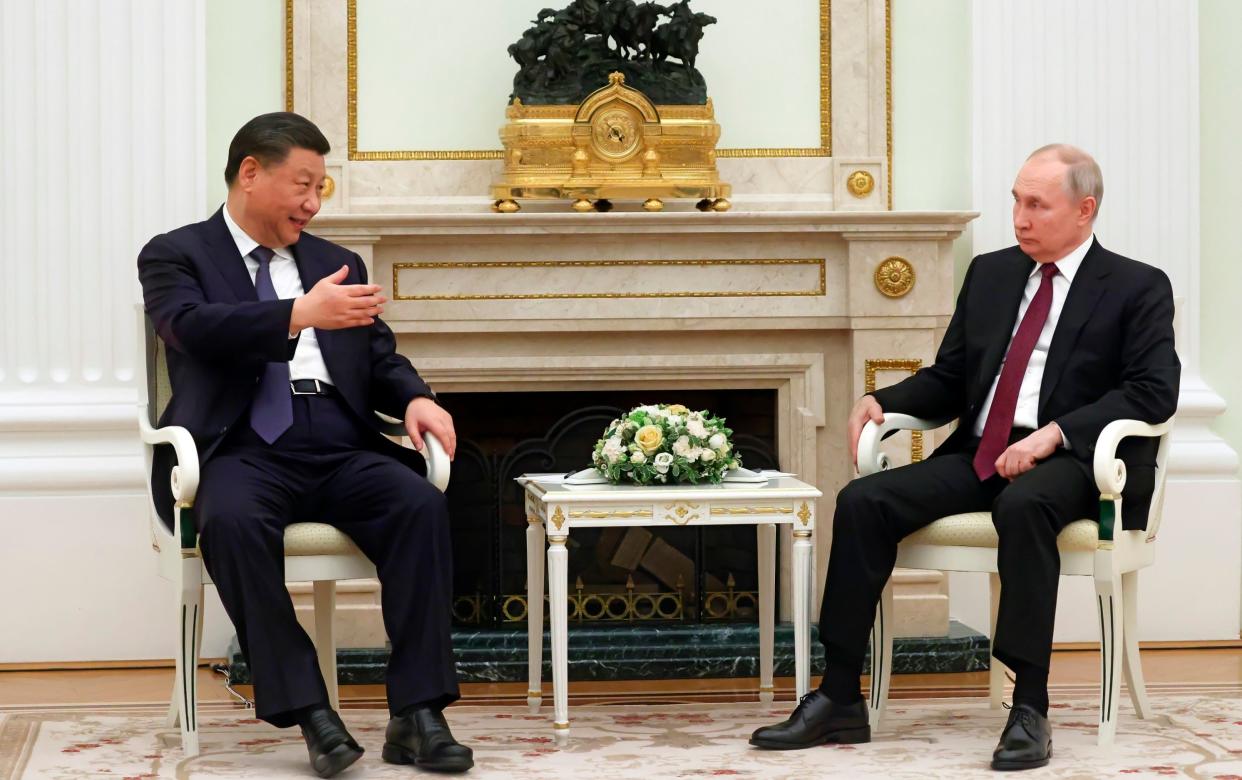

There is only one winner from Vladimir Putin’s monstrous war on Ukraine, and that is the Chinese Communist Party. To our eternal shame, Xi Jinping has spectacularly outwitted the West, drastically expanded his global influence, and turned Russia into a Chinese protectorate in all but name.

Russia was meant to have collapsed by now. Britain, America and Europe’s gambit was that drastic trade, financial and technological sanctions, a cap on the price of Russian seaborne oil, and substantial help to Ukraine would be enough to defeat Moscow. It hasn’t worked. For all of the sacrifices of the Ukrainian people, the war has reached a stalemate, at least until Kyiv’s counter-offensive.

The reason? China has quietly stepped in, bailing out Putin’s shattered economy on a transformational scale, swapping energy and raw materials for goods and technology. The sanctions are a joke. Russian-Chinese trade rose 41.3 per cent in the first four months of the year to $73 billion, financing Putin’s war. China’s exports to Russia were up 153 per cent in April 2023 alone; their rise more than cancels out the decline in German and French trade, as Robin Brooks, of the Institute for International Finance, points out. China’s trade has also shot up with Belarus, Kazakhstan, Georgia and Turkey, all with easy, porous access to Russia.

No wonder Russian society hasn’t imploded. There may no longer be any McDonald’s in Moscow, but sales of Chinese cars are buoyant. We were told Russia couldn’t survive without Western technology, but it is switching instead to China’s rival systems.

The quid pro quo is that Russia is now dependent on the CCP for its survival, and Moscow’s new paymasters will pitilessly flex their muscles. This is a triumph for Beijing’s mercantilists: they have permanently absorbed Russia into their orbit. If Putin, a nasty megalomaniac, survives his disastrous war, it will be as a vassal of Xi, the final humiliation. The only upside for the rest of us is that Russia is now less likely to use tactical nuclear weapons, an insane policy China would surely veto.

What is certain is that we are now truly in a new Cold War, a historic battle between the West and a resurgent Chinese civilisation-state. The emerging world grasps this, and is taking sides in this new world order. Tragically, China’s reputation is soaring, and America’s is faltering under the pathetic Joe Biden administration.

China has already brokered a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, endangering Middle East peace. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Brazil’s far-Left president, has “reset” relations with Beijing. In Latin America and Africa, the CCP’s influence continues to rise thanks to its Belt and Road initiative, the loans it dishes out, and the deals it strikes to corner the market in key materials and minerals. China is also undermining the Commonwealth. India is buying Russian energy.

Yet for all of these victories, future historians may yet remember the present moment as the CCP’s heyday, the moment we hit peak China, rather than the start of a new multi-decade, Han dynasty-style period of Chinese ascendancy.

The Chinese economy’s period of extremely strong growth is over, despite its prowess in AI and batteries, for three reasons. First, Xi cracked down on China’s oligarchs, the entrepreneurs who had driven so much of its progress but had started to throw their weight around. The CCP is once again in total control; there are no longer any independent power centres. Real capitalism is dead. Second, the savagery of its lockdowns, its obsession with zero Covid and the cover-ups of the past few years demonstrate that China remains a fundamentally closed society. There is no real individual liberty, no freedom and thus no chance of another sustained economic boom.

Last but not least, China’s population fell 850,000 last year, a harbinger of a looming demographic implosion that will turn dozens of cities into ghost towns, throttle the banking system, starve the military and threaten permanent stagnation. India is now the world’s most populous nation, with 1.428 billion residents, against China’s 1.425 billion, according to the United Nations, with America third at 340 million. China’s population is expected to shrink by almost half during the next three quarters of a century, to just 766 million by 2100 – a decline precipitated by its abominable one-child policy, a reminder of the immorality of top-down social engineering.

By contrast, America’s population will continue to grow, hitting 394 million by the end of the century, assuming the country holds together despite its bitter ideological divisions. Unless China’s productivity suddenly rockets, unlikely in Xi’s repressive climate, the gap between the American and Chinese economies may never quite close, or will take much longer to do so than expected.

These limits to China’s model coincide with the beginnings of a fight-back by the free world, symbolised by Italy’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road initiative. The West is no longer deluded about China’s intentions, its attachment to authoritarian imperialism, or its propensity to engage in espionage and dissembling, even if few realise the immensity of the challenge.

But at least the David Cameron-George Osborne “golden era” of close ties with China has long since been forgotten. Liz Truss is travelling to Taiwan next week to warn against China. The Aukus military pact is a great move, as is Britain’s decision to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Japan is rearming. India will become increasingly assertive. A Donald Trump or Ron DeSantis victory would accelerate attempts at decoupling the American and Chinese economies.

Confident countries that believe their ascent will continue for the foreseeable future don’t usually choose to precipitate a major war – for example by invading Taiwan. As Robert Tombs, the historian, has pointed out, it is when nations feel that they are running out of time or that they are being cornered that they lash out.

So what next? Can we avoid a calamitous, global conflict that will set humanity back 50 years, at best? Will China’s elites see sense and bank their takeover of Putin’s Russia? Or will they worry that their own window of opportunity is closing, and decide to gamble on an invasion of Taiwan, especially if the unfathomably weak Biden is reelected? Britain must hope for the best, and prepare for the worst.