Russian lander crashing into the moon may have broader implications for space race, experts say

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

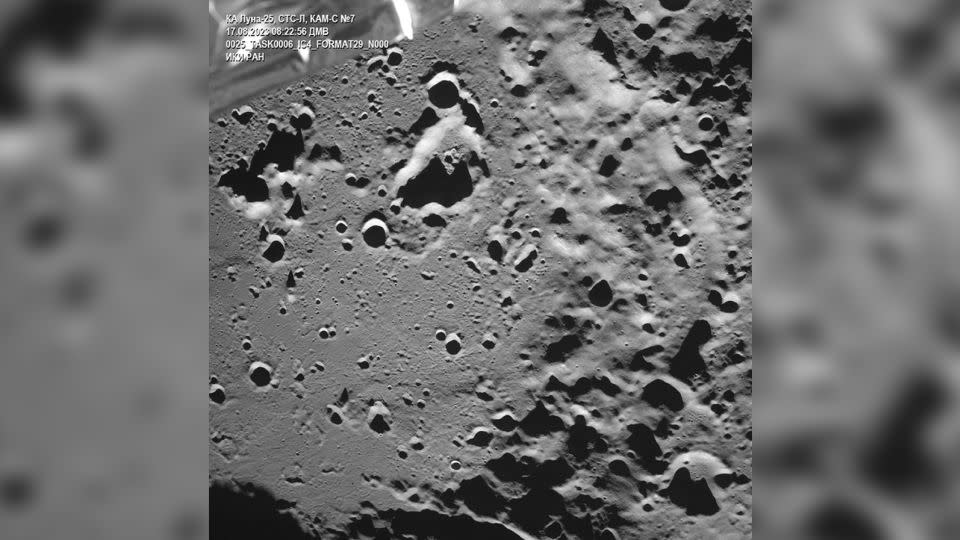

A Russian spacecraft malfunctioned over the weekend, sending the vehicle crashing into the moon. The failed landing attempt has experts questioning the future of the country’s lunar exploration ambitions and the geopolitical dynamics that underpin modern space exploration efforts.

The spacecraft, Luna 25, lost contact with operators at Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, on Saturday, August 19. By Sunday, the vehicle was declared dead.

Initial reports from the head of Roscosmos, Yury Borisov, indicate there was a problem with the vehicle’s engines, causing it to misfire as it attempted to adjust its orbit in the days before landing.

The failure was a major blow to the space agency’s ambitions. Russia had been seeking to prove that its civil space program, which analysts say has faced issues for decades, can still achieve the stunning feats it showcased during the 20th-century space race.

“Russia’s Cold War legacy will be just that — a legacy — unless they can actually do this themselves,” said Victoria Samson, the Washington office director for Secure World Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes the peaceful exploration of outer space.

Under the former Soviet Union, Russia managed to safely land seven spacecraft on the lunar surface, including the first-ever soft landing in 1966.

Borisov acknowledged that the Soviet successes of last century weren’t easily repeatable.

“We have to essentially master all the technologies all over again — of course, at a new technical level,” he said during an interview with Russian state media on Monday.

Borisov has offered assurance that Roscosmos can get back on track. He said the space agency will accelerate its next two moon missions: Luna 26 and Luna 27, which could give Roscosmos all the science it lost with the failure of Luna 25.

Still, space policy experts question whether the Russian government has the power or the will to make that happen, particularly as the country faces sanctions around the war in Ukraine and Roscosmos appears to be of diminishing importance to the Kremlin.

“Even if they said they were going to continue (the Luna program), that doesn’t necessarily mean anything at this point. And the question is: Can they continue? Do they have the capability to continue it?” said Robert Pearson, a former ambassador to Turkey, former director general of the U.S. Foreign Service, and a founding member of Duke University’s Space Diplomacy Lab.

The consequence of this failure, Pearson added, is that on the global stage, it raises the question of whether Russia is “seriously in the space race” at all.

A changing civil space landscape

Russia’s failed moon landing attempt comes amid a rush of other lunar exploration efforts, largely designed by countries that haven’t been seen as traditional space powers. Luna 25 was flying alongside India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft, which will attempt to land on the moon as soon as Wednesday.

More than a dozen other countries also have plans for moon missions in the coming years, including the United States’ ambitious Artemis III, which could land astronauts on the lunar surface as soon as 2025.

“I think it … speaks to how much the cost of space exploration has dropped,” Samson said. “It’s still not cheap by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s gotten a little more reasonable. … I think that’s why more countries are able to (attempt) it.”

But while the loss of Luna 25 may widely be seen as a setback for Russia’s space ambitions, it’s worth noting that putting a spacecraft on the moon remains an exceedingly difficult feat.

India’s last attempt, with the Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft, failed. And two other commercial spacecraft have also crash-landed since 2019.

Perhaps different expectations were placed on Russia, however, because of its extensive Soviet-era experience.

If India’s space agency manages to safely land its spacecraft, Pearson added, it could “really outline the loss of prestige and influence and technological ability on the part of Russia.”

The mission was also closely watched because of how the country’s civil space program has been evolving. In recent years, Roscosmos has been beleaguered by issues with funding, quality control issues and suspected corruption, Samson noted.

The space agency has also faced blowback from Western nations since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The European Space Agency, for example, was set to work with Roscosmos on the Luna 25 mission as well as several future exploration endeavors, but Europe pulled out of the partnership after the invasion of Ukraine.

Now, questions are swirling around how Russia’s closest modern space partner — China — might react to Luna 25’s failure.

The two countries had announced they would work together to establish the International Lunar Research Station, a moon base to rival plans by the US and its allies to create a permanent lunar outpost under NASA’s Artemis program.

Samson noted that China, which is so far the only country to soft-land spacecraft on the moon in the 21st century, has already been downplaying Russia’s role in the program.

“I’m sure China must be really wondering what they saddled themselves with” after the Luna 25 mission, Samson said.

Still, Samson and Pearson both noted that Russia continues to play a key role on the international stage. The country is the United States’ primary partner on the International Space Station, though Russia previously threatened to pull out of that operation. For years, Russia was also the only country capable of getting astronauts to and from the space station after NASA retired its space shuttle program. (Today, SpaceX has taken over that function for the US.)

Why missions like Luna 25 matter

The Luna 25 spacecraft was intended to land on the moon’s south pole. It’s the same region where India is aiming to put its Chandrayaan-3 lander and where NASA plans to put its astronauts as well as future robotic missions.

The widespread interest in the moon’s south pole can be attributed to one key feature: water ice. Scientists believe copious amounts of water are stored near the south pole, frozen solid in shadowy craters.

Water ice could be immensely valuable for the future of space exploration. The precious resource could be converted into rocket fuel for missions that explore deeper into the cosmos or turned into drinking water for astronauts on long-duration missions.

“That is really the big driver for why we need to head to the south pole — and they’re in sort of part of a ‘Space Race Part Two,’” said Dr. Angela Marusiak, an assistant research professor at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, in an August 18 interview.

Because orbital dynamics make the south pole difficult to reach, it hasn’t been as deeply explored as other areas. That gives Russia and every other nation with lunar ambitions a key reason to go: There is clear scientific — and strategic — interest.

But Pearson questioned why Russia chose to head straight for the south pole for its first lunar mission in nearly 50 years.

“All they had to do was land (somewhere on the moon) and they would have shown the world that they were in the space race,” Pearson said of Russia. “They took a desperate measure — in my opinion — when they should have picked a safer option.”

Which countries reach the moon, and when, could have implications for how scientists make use of the data gathered.

Exactly how information sharing will work is not exactly clear.

India, for example, is a signatory of NASA’s Artemis Accords, a document mapping out agreed-upon rules for lunar exploration that includes a commitment to sharing scientific data.

Russia, on the other hand, is not a signatory.

But Samson cautioned against characterizing these lunar missions as a race, suggesting those involved are opponents. Though it’s difficult to know exactly what dynamics will arise, the moon is a big place — and there is room for everyone.

“My concern is that if we look at this in an aggressive, adversarial manner,” she said, “then we will generate the exact circumstance we’re trying to avoid.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com