Russia’s War in Ukraine Is Making the Heat Wave in Asia Even Deadlier

Workers move blocks of ice into a storage unit at a fresh market amid a heatwave in Bangkok, Thailand, on April 25. Credit - Lillian Suwanrumpha—AFP/Getty Images

India’s southern state of Karnataka has a reputation for clean energy, with nearly half of its power supply mix being in renewables. But as a heat wave continues to scorch India and the rest of Asia since April and energy demands spike, the authorities have been forced to return to coal. Coal-fed power plants in the state are now reportedly back running full throttle.

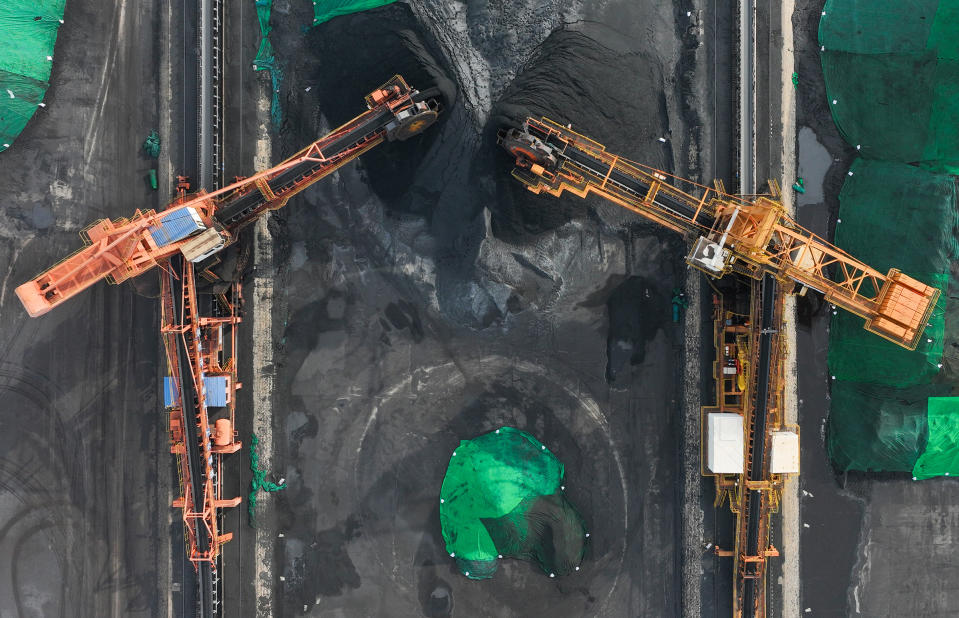

Karnataka is not alone in ramping up its coal burning. Year-on-year data from climate technology firm TransitionZero estimates a 14% increase in the use of coal plants in China in April. It’s the same story in many parts of Asia, where years of progress in shifting to transition fuels like liquified natural gas (LNG) and renewables are being undone by soaring energy use spurred by the unprecedented heat wave, which scientists believe is yet another tell-tale sign of climate change.

The impact of global warming has been acute in Asia. Singapore logged its hottest temperature in over 40 years last Sunday. And Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, and China have also all seen record temperatures in the past several weeks. The Thai government had to issue an advisory asking people to stay home to avoid falling ill. In the Philippines, many schools have been forced to switch to distance learning to protect students from heat.

The heat wave is already deadly on its own, but exacerbating the public health and economic effects in Asia is an unlikely factor: the Russia-Ukraine war. Europe’s boycott of Russian oil has caused a seismic shift in energy markets by soaking up global LNG supplies and forcing poorer countries to fall back on dirtier energy like coal, which in turn ramps up carbon emissions that heat up the planet.

Ukraine war derails Asia’s energy transition

A study by Energymonitor.ai last year found Asia has invested at least $490 billion in new gas infrastructure, led by Vietnam and China. The continent is the largest exporter and importer of LNG. Because of its relatively lower emissions compared to coal or oil, the gas is considered a “bridge fuel,” lowering the dependence on traditional fossil fuels like coal and oil.

But the Russia-Ukraine conflict has upended the LNG market. Europe was in desperate need of energy as winter approached but struggled to secure a necessary alternative even as it cut off piped gas from Russia. Despite lacking sufficient infrastructure, Europe started to dip into the LNG supply that would have gone to Asia, raising the demand and causing prices to jump nearly 10 times the average.

While some Asian countries like Japan have bought LNG at exorbitant rates, many others like China and India have simply cut down on imports by around a fifth, and smaller economies like Pakistan have been priced out of the LNG market altogether, resulting in energy shortages and eventual blackouts amid the heat wave.

Alloysius Joko Purwanto, an energy economist at the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia in Indonesia, said countries like Vietnam and the Philippines have built sufficient downstream facilities for LNG, but LNG supply issues have negated these advances.

While the spot price of LNG in Asia has come down from its peaks, the damage has already been done. Having experienced such a wild price swing has reduced the appetite for LNG in many developing markets, which have now come to see it as an unreliable fuel. These countries now feel uncertain to continue “with expanding their use of natural gas due to this kind of volatility of prices,” says Purwanto.

The heat wave is driving up coal use, and the poor are paying for it

As in Karnataka, the heat wave-induced spike has brought coal back into the center of the energy mix as talks of phasing out dirty fuel recede and focus shifts to surviving the heat. It’s happened before: a scorching heat wave and drought last year caused China to increase its coal power generation. The country, bracing to bear the brunt of Asia’s heat wave this coming summer, is not discounting the possibility of increasing coal energy use again. “We will do our best to promote stable coal production and increase production,” an official said according to state media.

Shi Xunpeng, a professor of energy economics at the University of Technology Sydney, said the effect of the LNG mess will be most felt in low-income communities. “Even small price variations will cause a significant challenge for them to access more clean energy,” he said.

Industries that rely on running on cooling facilities pass on their increased energy costs to cope with the heat wave to consumers, hitting the poor the hardest. Heat waves also increase the exposure of low-wage workers to grueling temperatures, leading to productivity drops.

A study from Dartmouth College found that based on historical data, economic losses of global regions due to heat stress is larger in the bottom income decile at 6.7% of their gross domestic product per capita per year, compared to 1.5% for regions in the top income decile. India, where up to 75% of the workforce depend on heat-exposed work such as mining, quarrying, hospitality, and transport, may account for 34 million of the projected 80 million global job losses by 2030 as a result of heat stress.

Heat waves are also scientifically linked to aggravated air pollution, threatening countries like India, where air quality is already one of the worst in the world. An estimated 1.67 million people died prematurely in 2019 because of pollution in India, the risk being greater for sections of the population living near coal-fired power sources.

Shi says governments are thus under greater pressure to look beyond their energy mix and make sure that disadvantaged communities do not suffer more as a result of reverting to traditional fuels. “We already have to be careful for the worst as the Russia-Ukraine war unfolds, and to look after other unfavorable conditions in the international energy market to make sure that the national economies and the disadvantaged groups will [experience] minimum impact from future unexpected changes,” he said.