Russian artist uses blood donated by Ukrainian fighters to send a message to Vladimir Putin

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Andrei Molodkin would admit he has a thing for blood. He enjoys its colour, its deep sanguine tones. He appreciates too, its viscosity, how it can sometimes feel as sticky as crude oil. And he appears to enjoy the shocked reaction and clammy-handed squeamishness of audiences, when he makes use of real blood, in particular real human blood, in his art work.

Some have been censored, their labels removed from exhibitions, as though the curators know the trouble that can come with mixing blood with politics, or politics with art. Other times he has had to defend the validity of his work.

Despite that reaction – or perhaps partly because of it – he keeps on using it.

Now the 56-year-old Russian artist is set to shock again with a new piece, a sculpture featuring the face of Vladimir Putin, with the space behind filled with human blood. It makes the Russian leader appear to be drenched in the vibrant red liquid. Blood soaked. Awash with blood.

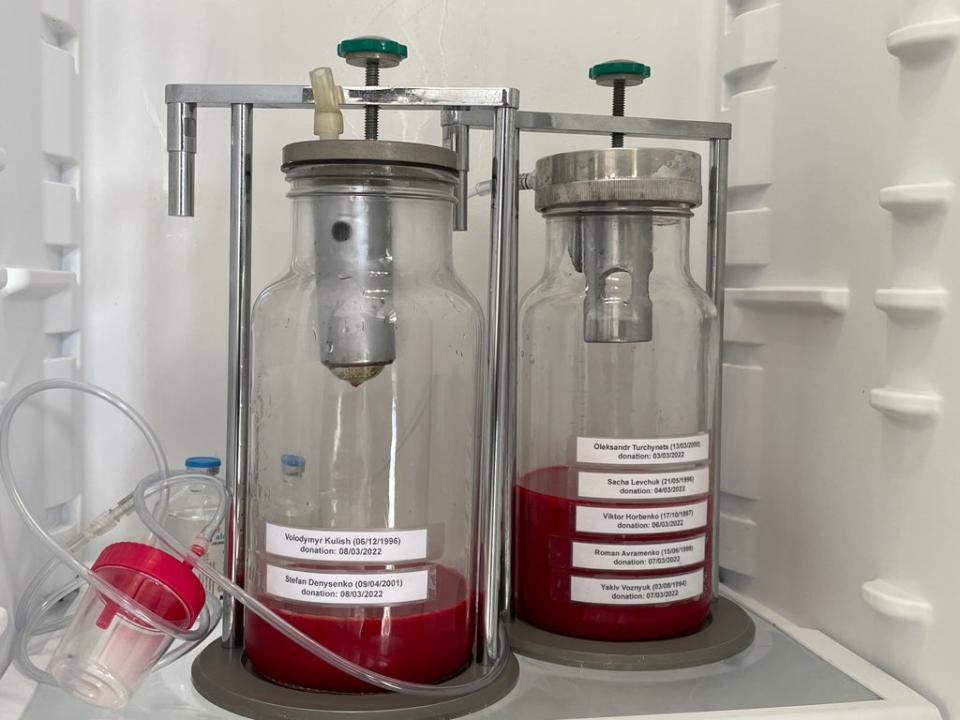

And it is not just any old human blood; it is blood donated by eight Ukrainian friends and associates, currently fighting to defend their country against Putin’s army. Part of the hastily trained army of volunteers who came together in the weeks before and after Putin’s invasion of their country, some are now close to the frontlines. Others are working in back-up roles, making deliveries and so forth.

All of his artistic collaborators know the risk they are taking. None want to give up any more of their own blood. Yet, they are part of the defiant resistance that has so far shocked Moscow, and initially western military officials, with their success against what was considered one of the world’s most effective military machines.

All the world will see this is not a human, but a portrait with the blood of everyone, children, woman, adults, grandfathers

Molodkin’s piece is called quite simply Putin Filled With Ukrainian Blood. One of the men who donated blood for the project is Olexander Levchuk, a 33-year-old landscape designer from the western Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi. He gave the blood to Molodkin at the artist’s studio, The Foundry, in southwest France, and then returned to Ukraine by bus.

His wife, Kristina, 26, and their two children, Ivan, 9, and Kyrlo, 7, have been staying at The Foundry for more than two months, with some other Ukrainian friends, keeping in touch with their loved ones by text messages or an occasional call.

Speaking from The Foundry, situated in Maubourguet, close to the city of Lourdes, the young woman tells The Independent, her husband was happy to provide some blood for the project because it highlights the human cost of Russia’s invasion.

“It’s filled with Ukrainian blood and that’s a clear message to show that Putin is full of Ukrainian blood,” she says. “All of us would like to participate. All the world will see this is not a human, but a portrait with the blood of everyone, children, woman, adults, grandfathers. Every population.”

And how did she feel when she first saw the work of art? Speaking in Russian, which Molodkin translates, she says she experienced “goose bumps” and was shocked. “I understand how much blood of the children and the innocent people [is lost],” she says.

She says she cried when she saw at it ... the horrors on the battlefield and alleged war crimes being perpetrated on her country, being symbolised by the piece of art. “I think it is the most true portrait of [what is happening now], the people filled by Ukrainian blood, now fighting for their freedom or independence.”

In a WhatsApp message sent from Ukraine, her husband, Olexander, says he was very happy to be part of the struggle, and the project. “We fight here for our hope and freedom! Everything will be changed and we will have a great country. We are all together,” he says.

He adds: “My blood as a Ukrainian is very important in this sculpture by my Russian friend. Together, we show [Putin] is a criminal man. He is made by our blood by many, many women, children and men.”

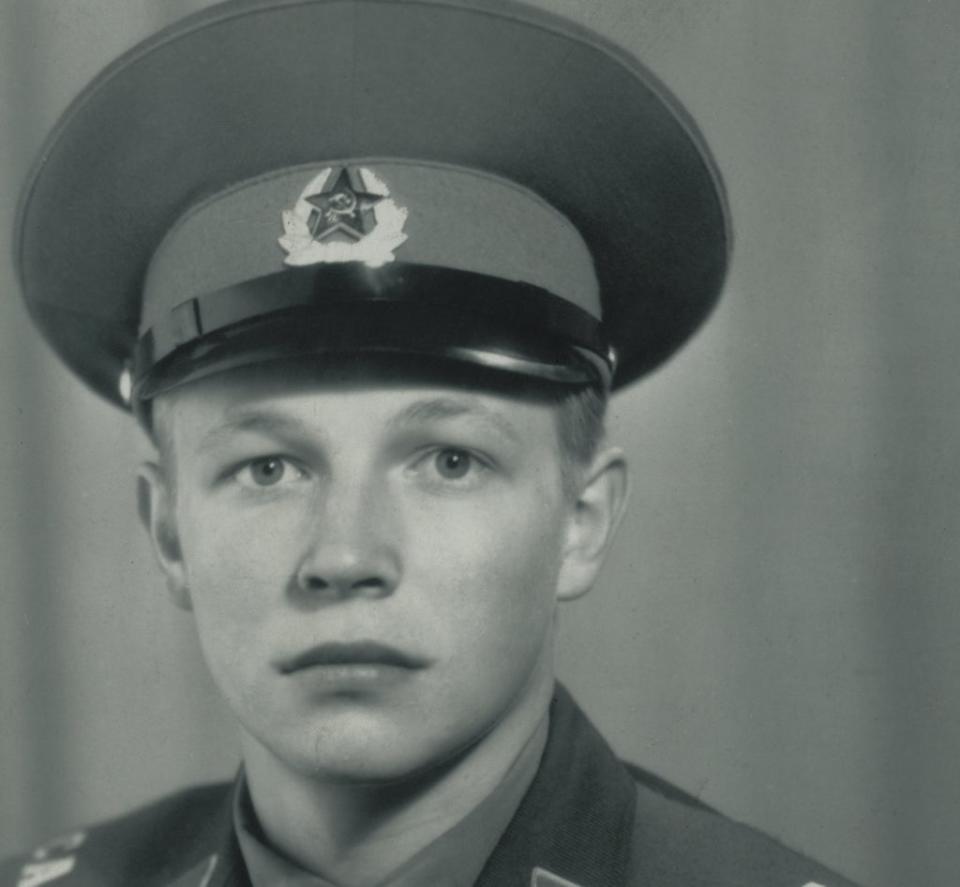

Molodkin says he had a striking insight into the shocking visual power of blood when he was a young conscript in the Soviet Army, serving for two years from 1985 to 1987 and often transporting missiles on 24-day missions across Siberia.

It was a perilous, hard-edged existence. Included in the rations handed out to the soldiers, were cigarettes and black Bic-type pens that the troops would use to write letters home to family and friends. Molodkin used his to sketch things and draw. As he did not smoke, he would swap his cigarettes for the pens of his comrades.

He remembers the man shooting himself in the chest as he sat in his truck. The other soldiers pushed his body on to the ground, and went to eat at the canteen

The missions were arduous and the soldiers were often bullied and punished, for things such as falling asleep while on duty. Molodkin, who was born in a small town in northwest Russia called Buy, and spends much of his time these days in Paris, says one man he knew was bullied frequently and became depressed.

He remembers clearly the day the man took his own life, shooting himself in the chest as he sat in his truck. The other soldiers pushed his body on to the ground, and went to eat at the canteen.

“He was just lying there, like an animal, and then they moved him,” he says.

The man had shot himself in the chest, and he had continued to bleed. When they finished moving him, the snow was streaked with blood for 50 yards. “And until now, I think that a person can give his best last signature like this, by lying in the road,” he says. “And everyone who saw it, remembers it, because he shot himself in the heart and the blood kept going, and the red line keep going like this.”

A number of Molodkin’s works have featured human blood. In 2009, he was invited to take part in the Russian exhibit at the the 53rd Venice Biennale. The multi-media work he offered was entitled Le Rouge et le Noir and consisted of two hollow acrylic block replicas of a celebrated Greek statue.

Also contained in the work were two pumps that appeared ready to mix their contents of blood and oil. The oil was apparently from Chechnya, which Russian forces have twice invaded, partly to secure resources, and the blood belonged to a veteran of the conflict, according to Molodkin’s labels that accompanied the piece.

A review of the exhibit by Russian curator Margarita Tupitsyn for Artforum, noted that his actions turned “the installation into a revolt against the post-Soviet cultural establishment’s disengagement from political discourse. And sure enough, the pavilion’s curator scrapped the inscription at the opening.”

People were angry that I hadn’t used Catholic and Protestant blood. They felt cheated that I had only chosen to use Catholic blood. In Derry people have given blood for freedom

In 2013, he produced a work, Catholic Blood, for the Void Gallery in Londonderry, in Northern Ireland. The piece also made use of acrylic, and featured an impression of mirroring the rose window of the Palace of Westminster, home of the British parliament, and contained the donated blood of 36 Catholics.

The piece was a meditation about an act of parliament from 1829, the Catholic Relief Act, which had allegedly blocked Catholics from becoming prime minister, or more technically, “providing counsel” to the monarch. Constitutional scholars disagreed with Molodkin and said he was wrong, but he pointed out there had never been a Catholic occupant of 10 Downing Street. (Indeed, the ascent of Boris Johnson to that office in July 2019 marked the first time a baptised Catholic had served as prime minister.)

“People were angry that I hadn’t used Catholic and Protestant blood. They felt cheated that I had only chosen to use Catholic blood,” Molodkin toldThe Independent in 2013. “It was never my intention to mix religions – the intensity is in the separation… In Derry, there is a legacy of people who have given their blood for freedom, politics and religion.”

Several others have featured oil. An exhibit from 2005, entitled Sweet Crude Eternity, hosted by the Kashya Hildebrand gallery in New York, included sculptures of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, internal human organs and words such as “democracy”. All contained oil. “Oil is like a global language of our world,” he told the BBC. “A country can communicate with another just through energy or a resource.”

In 2019, he collaborated with the Russian artist Erik Bulatov, now aged 88, for an exhibit in Charleroi, Belgium, titled Black Horizon, and which examined censorship and propaganda, and which invited attendees to donate their own blood. Molodkin had been partly inspired by the suspended prison sentences handed down to London rappers who fell foul of the law for mentioning rival crews in their lyrics, which the authorities said breached an anti-gang injunction.

Why do so many of his works feature these fundamental compounds?

There is blood and oil at the centre of the conflict. We can tell in different ways that in every barrel of oil we have Ukrainian blood, or we can say that we paid blood money for this oil

“Because you can see these situations, there is always blood and oil at the centre of the conflict,” he says from France. “We can tell in different ways that in every barrel of oil we have Ukrainian blood, or we can say that we paid blood money for this oil.”

He says the conflicts in Chechnya were directly linked to securing oil resources. “We know that they sent Russian soldiers who died there to control the oil … We know how much blood you have to give for this amount of oil.”

He says the same can be said of the US and UK’s invasion of Iraq. “Blood and oil, all the time circulating, and of course it’s the official language, and the language of the power. It’s anywhere. It’s in Iraq, it’s in Iran,” he says. “So I speak the same language that Putin speaks – blood and oil.”

Molodkin’s most recent piece, Putin Filled With Ukrainian Blood, measures 50cm x 70cm x 7cm. With the help of friends its likeness has been projected on to buildings across Ukraine, including Mariupol, where Russian forces have been conducting a months-long bombardment and where many hundreds of civilians were reported to have been killed. War crimes investigators have opened inquiries and Ukraine’s president, Voldomyr Zelensky, has called for a Nuremberg-style tribunal.

It was also beamed in Slovenia, and its likeness shown at a church in central London. His supporters say it is better the church remains anonymous. It is set to go on display at The Foundry, at an event featuring the Slovenian avant guard, industrial band, Laibach.

Molodkin also has plans to show it earlier, at the Victory Day Parade that Soviet, and now Russian leaders, annually oversee in Moscow’s Red Square. It is held today, 9 May, and marks the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi troops, and their surrender to Soviet forces in Berlin.

“We plan to show it on the Red Square for the Victory Day. We have some plan. Many people working on it. Putin has to understand it,” he says.

He believes it will take many years for Russia and Ukraine to rebuild the relationship once enjoyed between ordinary citizens that Putin has wrecked. He says that can only happen after a change in power at the very top in Moscow, so that the propaganda used by Putin can be exposed. Right now, he says, 75 or 80 per cent of people in Russia support the war.

What does Kristina, the young woman whose husband is among the blood donors, think of the plan to show the sculpture in Red Square? “I believe that this portrait of blood can stop the propaganda and people can see the real things and understand that this is not a “special military operation”, and that [Putin] has come to kill people,” she says.

“I really believe that if people in Russia see it, maybe it’s by magic or somehow, they will see how propaganda functions, and they can stop it.”

Olexander feels the same, and says art has its own power. “All the world needs to know who [Putin] really is,” he says.