Russian space programme facing existential crisis as Elon Musk helps US relaunch Nasa ambitions

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It took four international crews and almost a year before anyone onboard the International Space Station could locate the air leak, untraceable by equipment at hand, which had been driving the cosmonauts insane.

One evening last October, Russian cosmonaut Ivan Vagner in a desperate attempt to find that tiny hole sucking up precious air ripped up a tea bag inside one of the station’s segments, sending the tea leaves flying into weightlessness. A day later, he saw the tea leaves cluster around a tiny scratch that had been leaking air all along.

Mr Vagner’s ingenuity won him plaudits back home but the incident at the 22-year-old core segment of the station has laid bare Russia’s withering space dream as the country is nearing the 60th anniversary of the first human space flight. By the end of February, the Russian space agency reported six scratches on the Zvezda module which were leaking air.

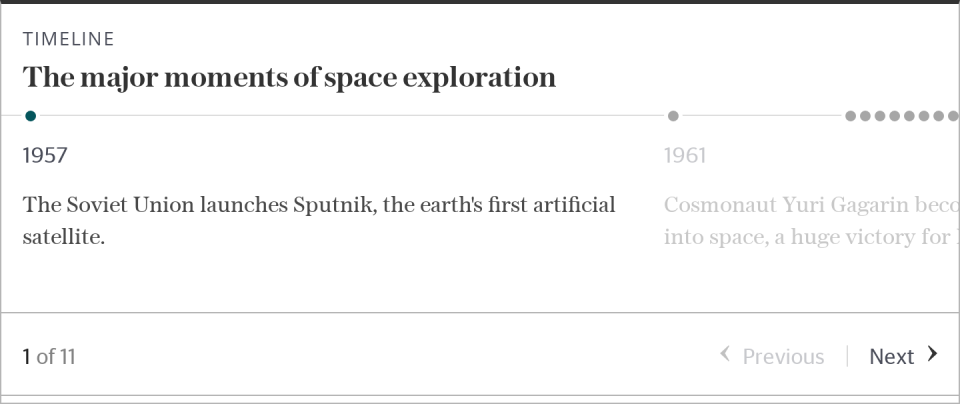

Yuri Gagarin took off for his maiden flight 60 years ago on Monday - 12 April, 1961 - in a triumph of Soviet science in its rivalry with the United States. Now Russia’s landmark space programme is facing an existential crisis due to mismanagement and a lack of vision as the United States and China have left Russia far behind in the space race.

Launched in 1998, the International Space Station was supposed to serve for no more than two decades, and, unless extended, the current agreement would see it shut down in 2024, leaving Russia without tangible space presence while the US is busy with a flurry of other projects including a manned mission to the moon.

“What Gagarin started for Russia would be over if Russia were to ditch its ISS programme in 2025 because there will be nowhere for Russian cosmonauts to fly to,” Ivan Moiseyev, who heads the Space Policy Institute in Moscow and used to advise the Russian government, told the Telegraph.

Senior officials in charge of the orbiting lab have been crying for help to save the space programme which no longer delivers any ground-breaking achievements.

Vladimir Solovyev, director general of the state-run RKK Energia corporation which oversees the Russian segment of the ISS, in November warned about “an avalanche of broken equipment” onboard as soon as in 2025.

Veteran cosmonauts like Gennady Padalka have been outspoken about the growing technology gap between the US and China and Russia.

“We’re still flying on the same stuff that we inherited from the Soviet Union,” he lamented in an interview at the end of 2019, adding that his generation “has not created anything new as far as manned space flights go.”

The Soviet space programme was an indisputable achievement of the Communist regime and the ultimate proof of its superiority but Russia’s space industry has struggled to find its purpose since the fall of the Soviet Union.

“Russian government under Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin have been busy exploiting the technological and industrial legacy of the Soviet space programme but now we’re facing the question ‘What’s next?’,” Pavel Luzin, an independent space expert, told the Telegraph, describing the space programme as one of the last remaining “insignia of Russia as a superpower.”

Russia’s clunky but incredibly reliable Soyuz spacecraft, designed in the 1960s, was the only link to the International Space Station for nearly ten years after the US mothballed its shuttle programme in 2011.

Russia has cashed in by sending Americans into space, charging NASA about $80 million (£58 million) per seat.

The Americans were reportedly annoyed by the high price tag, and further cooperation in space has been hampered by heightened tensions between Russia and the US which have been likened to the Cold War era.

When Elon Musk’s SpaceX blasted off for its first mission to the ISS last November, breaking Russia’s monopoly of nine years, many in Russia looked back at the past decade as a missed opportunity.

Maxim Surayev, a Russian cosmonaut who spent two six-month stints in orbit in 2010 and 2014, was among those who criticised the Russian space agency for failing to modernise the industry while racking up profits from American astronauts.

“Yuri Gagarin, I’ve sorry, we’ve screwed it up,” he tweeted last October while posting a video of NASA test-launching a new rocket booster that should send Americans back to the moon in 2024, something that is out of reach for the Russian space programme.

Roscosmos in recent months has flooded the media with announcements of new rocket projects, plans for a moon base and international cooperation.

Yet, an overwhelming majority of those projects are merely blueprints unlikely to be ever completed as several Soviet-era companies that once designed and produced rockets have fallen on hard times, often losing their entire production facilities to real estate development.

Nauka, the new module for the International Space Station is expected to be launched this summer - 14 years after the original date. The heavy-lift Angara rocket, designed in 1992, was first test-launched in 2014 and still has not replaced the Soviet-era Proton. Even when it is fully operational, Angara will still be several steps behind SpaceX’s reusable rockets.

Mr Moiseyev of the Space Policy Institute speaks of Russia pursuing projects like Angara as inertia motion since “enormous amounts of money has been spent on it already, and for officials, it’s too late to say that it’s not needed or outdated.”

Another controversial space investment is Vostochny, Russia’s news launchpad in the Far East that has already cost over £2 billion and been marred with corruption scandals which led to several convictions.

It was only after Russia started building the launchpad, which is supposed to be replace the Gagarin-era facility in Kazakhstan, that the questions were raised about its location: travel time from the other side of the country where the spacecraft are assembled is too long while its relative proximity to the Pacific Ocean would mean that Russia’s landing vehicles would have to be phased out.

Industry experts describe the 1990s as the golden era of cooperation between Russia and the US in space but the growing Russia-US confrontation is undermining the decades of joint work.

Russia has recently publicly refused to join the US-led Gateway project for a lunar station, opting out for cooperation with China but industry experts are skeptical of the idea, pointing to China’s reluctance to share technology with other countries.

After years of under-funding, cosmonauts and space industry insiders speak about a lack of long-term vision for space exploration.

A year after the planned release date, Russia still has not unveiled its long-term strategy for space research for the decade ahead, raising questions about the future of the industry which is estimated to employ a quarter million people.

“Russia is now at the crossroads: either we keep flying to the ISS, rip our chunk off the station and do God knows what with it, or we try to cooperate with America and Europe, says Mr Luzin. "In that case we need to fix our relations, but with Vladimir Putin in power it is problematic.” -