200 people could be left homeless after Sacramento County closes two emergency shelters

Britt Macias felt something unfamiliar in a dingy motel room two years ago: hope.

She had been homeless for months, but on July 13, 2021, she and her two beloved dogs moved into the Vagabond Inn and slept inside. She quickly got a job she could walk to, helping other homeless people; the hotel provided her meals, so she planned to save up her money.

Maybe she could scrape together enough to fix her car, even rent an apartment.

Her life had become a series of catastrophes. But finally — finally — here was something that seemed good. It seemed like progress.

Nearly two years later, Macias, 38, is still stuck in the same roach-infested hotel that the county has vowed to shut down at the end of June, evicting whoever is still there. Every modest gain she’s made — her new job, her ability to see how much she’s been able to accomplish on her own — would be wiped out if the county’s plan forced her to move back onto the streets.

Homelessness: Our urgent human crisis

Follow our ambitious, newsroom-wide series examining the growing problem of homelessness across Sacramento and California in 2023, examining government policy, money, addiction, mental health and more.

She walked into the Project Roomkey hotel believing it would be a step toward a real home. But in April, the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors voted to close the two remaining COVID emergency shelters without a plan to house everyone who lives in them. Last month, that amounted to more than 200 people.

To Macias, it was almost unbelievable.

“I thought that I would get help with housing,” Macias said. “The help that is, really isn’t any help at all.”

Under the supervisors’ plan, downtown’s Vagabond Inn will close first, at the end of June, and Rancho Cordova’s Comfort Inn will close at the end of October. The ramp-down plan included funding for on-site navigators and “rehousing services” — new resources that began less than three months before everyone in the Vagabond Inn would have to get out.

On average, the participants had lived in Roomkey hotels for nine months, with access to outside rehousing services. How the rehousing timeline could accelerate enough to keep everyone indoors is unclear.

Since the plan passed, the Department of Human Assistance has not hired two of five funded on-site navigators, with the end of the shelter swiftly approaching. As of May 15 — six weeks before the Vagabond is supposed to close — the three hired navigators had not yet met with any of the residents.

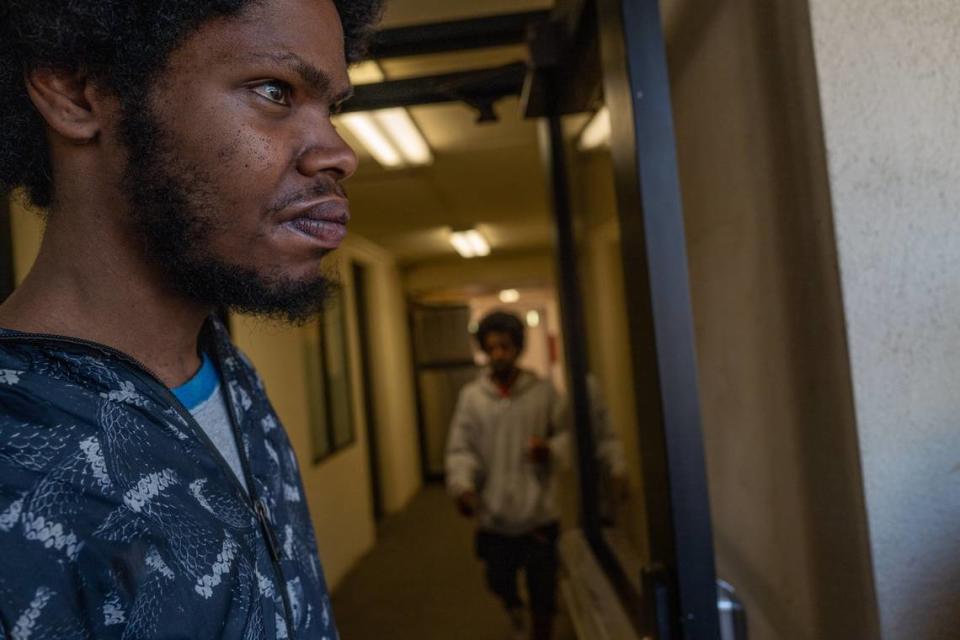

Benjamin Frazier, 26, has lived at the downtown hotel for eight months. He is soft-spoken but did not mince words:

“I feel like they’re just slapping us on the hand and saying, ‘You figure it out.’”

Social workers ‘cannot assist’

A document from the Department of Human Assistance shows that Sacramento County officials deployed a rehousing effort mere weeks before funding for a COVID emergency homeless shelter was set to expire.

Though the agency expected the Board of Supervisors would extend the program beyond the end of April, residents said the outreach still came unnervingly late in their stays.

The document shows that in the first two weeks of April, county officials planned informational meetings between social workers who expressly “cannot assist with connections to resources or housing” and residents at the Vagabond Inn.

“They could have had us meet with the county a lot sooner,” said Richard Washington, frustrated with the delays. Washington has lived at the Vagabond Inn since September.

Project Roomkey was only supposed to exist for three months, said Julie Field, the Department of Human Assistance division manager who has overseen the hotels since they opened in 2020. Designed to address a public health emergency — not homelessness per se, but COVID — Roomkey, she said, was never intended to provide meaningful help so residents could find a more permanent home. That role would fall to outside agencies.

“PRK is strictly a sheltering program,” Field said. “It’s meant to keep people safe from the pandemic, keep them from getting sick, keep them from spreading the virus. It is not a rehousing program. There’s no true rehousing components within the program.”

Still, she said, 26 people from the program were already slated to move into public housing units, and program staff had found an additional 18 to 20 room-and-board slots.

“That right there,” she said, “is a huge swath of people.”

Project Roomkey housed 212 people as of April 17, county spokesperson Janna Haynes said, and 44 people represents about 21% of them.

Field said that her department had worked with Sacramento Steps Forward to bring on a dedicated housing navigator for the 200 or so people living in the hotels last June; that person works half-time. She said that the county also attempted to hire two additional housing navigators for the program in the summer, but that deal fell apart by September.

“The intent was there,” Field said. “It’s just, we weren’t able to get it going.”

Field could not say how many people would end up back on the street once the hotels shuttered. “I have no idea,” she said.

She acknowledged, “There will be some folks that end up returning to the streets.”

‘We’re people at the end of the day’

Macias worked as a case manager at Sacramento Self-Help Housing before an eviction left her living in her car in 2021. She said that the meetings in April gathered information about the residents that the county should have already had. Frazier and Washington found the process redundant as well.

“They talked about these ‘options’ that we have,” Macias said. “There’s nothing.”

She has a coveted emergency housing voucher — and can’t find a landlord who will accept it.

About 140,000 people in the county live in severe poverty, and the lack of coordinated effort to ensure that Project Roomkey residents had a dignified place to live made Macias feel dehumanized.

“The only thing f------ separating you from me is a f------ house,” she said. “Everybody seems to f------ forget: We’re people at the end of the day. OK? You’re one paycheck away from being homeless yourself.”

We called – found only three vacancies

The Board of Supervisors said that as Project Roomkey “ramped down,” new housing navigators would take a more hands-on approach in helping residents find permanent housing. However, more than a month after the supervisors passed the new funding, Field said, those navigators had not begun contacting residents.

In the interim, officials provided the homeless residents an extensive list maintained by the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency of 160 properties, most of which were associated with a phone number for prospective tenants to call themselves.

The Sacramento Bee called every number on the list. Out of 148 properties with a phone number, The Bee was only able to identify three properties that had immediately available housing.

A few rooms were available in an SRO, but only for people who had a referral from a social services agency; one unit was available for two seniors over 55; and a couple of apartments were open in a complex in Meadowview. The Bee determined that at least 64 of the properties contacted had a waitlist, generally one that was months to years long.

A single-room-occupancy building downtown that was only for veterans had a wait of at least a year and a half.

Another property was trying to fill a vacancy with people who had applied for affordable housing there in 2015 — eight years ago.

In making 148 phone calls, The Bee only spoke to staff at seven properties who said they were not working off a waitlist (though most of them still had no available units to offer the people on their “interest lists”).

At least 33 phone numbers on the list did not lead to an affordable property at all. Three staffers who answered the phone said they actually only had market-rate units in their buildings. Another staffer said he had no record of the building in question. Two of the properties were still under construction and won’t exist until 2024. Another property had burned to the ground. The list contained 26 numbers that appeared to be disconnected or non-functional. Five of those numbers connected callers to scams, such as an offer to “win” a gift card or a $100 Walmart rebate.

The Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency has not responded to questions about the list of properties.

Amber Box-Matson, who has lived at the Vagabond Inn since November, said she had called many of the numbers on the list. She said it was fruitless: “There’s no openings right now.”

Box-Mason said she believed she had a housing navigator, but that person hasn’t returned her calls in at least a month. She is trying to find a home to avoid having to live in her car again, and she’s also very motivated by the dream of regaining custody of her four children, three of whom are under 18.

Because of a strict no-visitors policy, her children aren’t allowed to visit her in the hotel. Between that and the odd hours she works as a restaurant cook, she struggles to see them as much as she wants.

Box-Matson worries that she’ll end up back in her car when the hotel closes. In that scenario, she had “no clue” what she would do, except for one thing:

“Cry,” she said. “I’ll cry.”

‘People back into the street’

Frazier and Washington recently bought a tent together, even as they were frantically applying for housing.

Frazier was adopted and recently met his biological parents, who are also homeless. It was as if every force worked against him — when he took one step forward, he got two shoves back.

His aspirations are humble. All he wants is a small apartment where he can try to stay healthy, try to get a job and live quietly with his little dog. These, he said, appear to be out of the reach of the county’s affordable housing bureaucracy.

And after failing for eight months to transition Frazier into a stable apartment, the county was now pursuing a backward plan that, he said, would just make the homelessness crisis worse.

“It’s not making sense,” Frazier said. “You’re closing it to put money towards funding for other homeless people on the street, but you’re about to send 200-something people back into the street. It doesn’t sound right.”

Tami McGraw, 59, lives in the Vagabond Inn with her cat. “We need this place,” she said. “If this program gets shut down, a lot of people like me and worse than me are gonna be out on the streets and dying.”

The Bee’s Renée C. Byer contributed to this story.