This Sacramento lawyer helped desegregate housing. A film series tells his legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

From a young age, Mazuri Colley had people coming up to her telling her what her grandfather had meant to them.

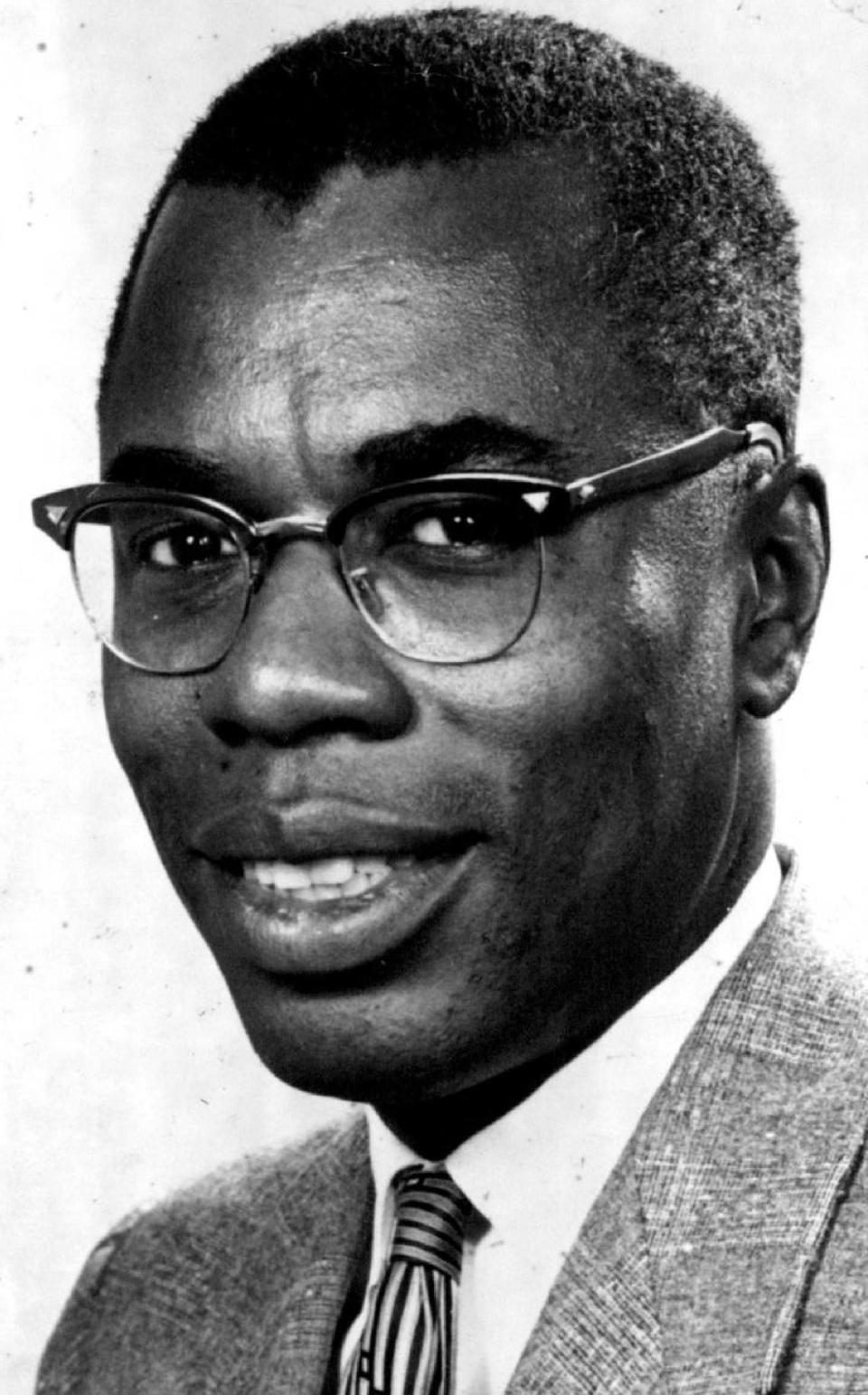

The now 39-year-old Colley is the granddaughter of Nathaniel Colley, a Sacramento attorney who helped desegregate housing locally by suing over the New Helvetia public housing project in 1952. He worked with others to get the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn California Proposition 14, a 1964 initiative approved by voters that allowed property owners to discriminate when selling.

“I guess I’ve always known about the importance of his legacy, even while he was still alive and then more importantly, after,” Colley said. “As the years go by, it sort of becomes bigger and bigger.”

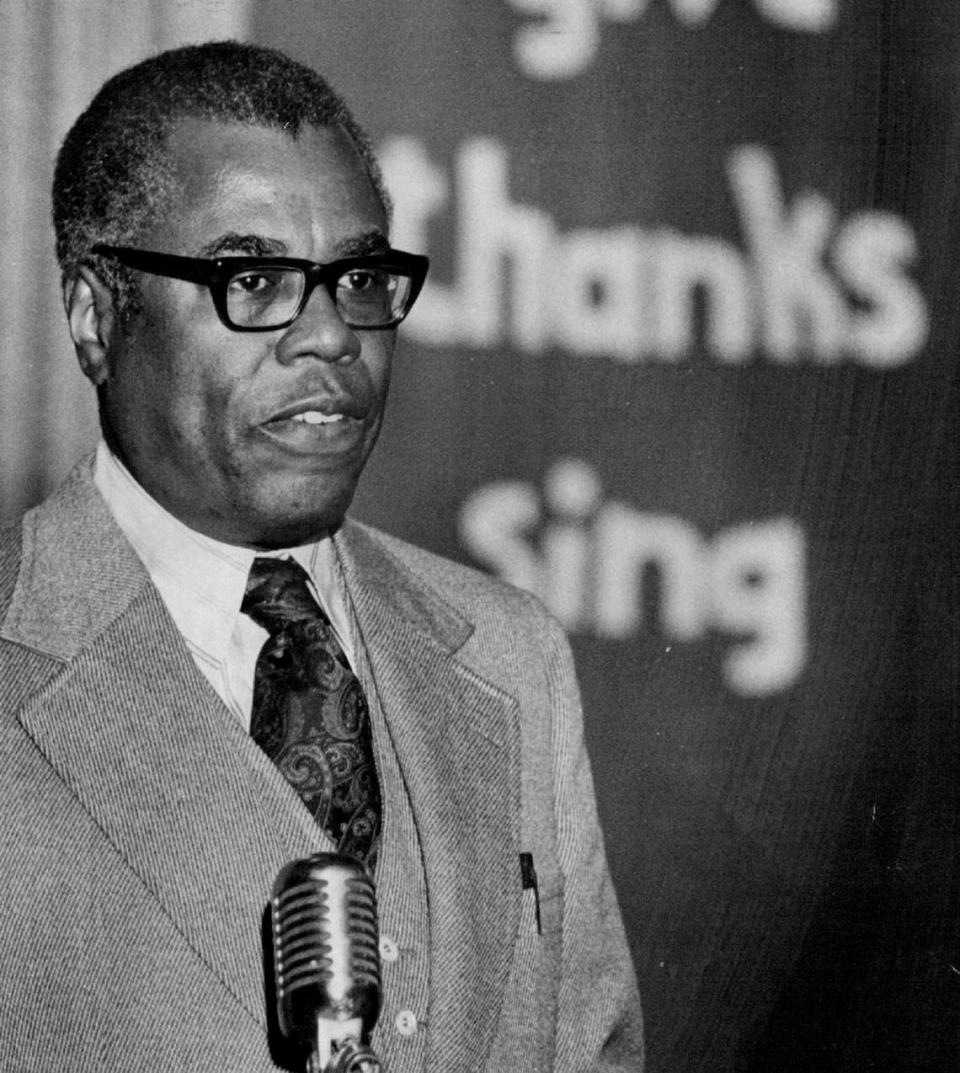

The elder Colley, who died of brain cancer in 1992 at age 74, won recognition in his lifetime. But the national reckoning spurred by George Floyd’s 2020 murder has been followed by a wave of renewed interest for one of Sacramento’s civil rights heroes.

Honors have included the city designating both Colley’s former 1810 S Street office and South Land Park home as historic landmarks; a local high school that opened in 2021 being named after him; and Colley being one of the subjects in the Center for Sacramento History’s short film series, “Unlocking the Past: A History of Prejudice and Racism in Sacramento.”

‘The preeminent civil rights pioneer in Sacramento’

Originally born into poverty in Snow Hill, Alabama, Colley came to Sacramento after studying with George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute, serving in the Pacific theater with the U.S. Army in World War II and graduating from Yale School of Law in 1948.

Colley became Sacramento’s first Black attorney in private practice, according to the Sacramento Observer, and soon built a successful career. He also was active with the NAACP, with the New York Times noting in Colley’s obituary that he’d served as the organization’s western regional counsel and national board member, among other roles.

Among those who’ve helped burnish Colley’s legacy in recent years is Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg.

“We have a sacred obligation to remember and know the stories of all the civil rights pioneers, known and unknown and Nathaniel Colley was the preeminent civil rights pioneer in Sacramento,” Steinberg said Tuesday.

The film about Colley’s work is one of three out so far in the Center for Sacramento History’s series, with another focusing on the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Sacramento and the third offering a warts-and-all look at pioneer John Sutter. The series, which recently won the center the American Association for State and Local History’s Leadership in History Award of Excellence, can be watched on YouTube.

An eye-popping collection of Colley’s papers, which have been in the center’s possession since 2010, make the film especially compelling.

“Everything that you see in those films has always been a part of our collection,” said Center for Sacramento History city historian Marcia Eymann. “It’s just getting it out there and people don’t know it exists and trying to tell a broader story.”

There’s a Western Union telegram from January 1957 to Colley from Harry Belafonte. The famed singer, who was active in the civil rights movement, told Colley, “Hold ‘em Joe,” a lyric to one of his songs. Colley was about to go to trial representing Oliver A. Ming, a Black veteran who’d sued over housing discrimination.

A report prepared for the city by architecture and historic preservation firm Page & Turnbull in June noted that Colley had already won the suit he’d filed over the New Helvetia project, which had only reserved 16 of its 310 units for African Americans.

Colley and his legal team won the Ming case as well, with its ruling making it so “developers and builders who received federal funds for housing projects could not engage in racial discrimination against individuals who were qualified and wanted to purchase a home,” according to the Page & Turnbull report.

But the housing desegregation work wasn’t complete; Colley went on to serve in John F. Kennedy’s presidential administration on a commission that helped desegregate federally owned housing in 1962. Kennedy had written to Colley in an Aug. 20, 1960, letter in the center’s collection, thanking him for his service on a Democratic Advisory Council committee.

“I know you agree with me that our country must have new ideas if we are to maintain our position of leadership,” Kennedy wrote. “Your work has made important contributions toward this objective.”

The collection also includes a speech Colley wrote when he appeared before a U.S. Senate committee in 1987 urging the confirmation of his friend from McGeorge School of Law, Anthony Kennedy, to the U.S. Supreme Court. In his speech, Colley quoted Kennedy’s remark of landmark 1954 decision Brown v. Board of Education: “The only thing wrong with Brown is that it wasn’t decided 80 years earlier.”

Colley wrote that most American Black people viewed the Brown decision “as our Magna Carta” and that he wished to reciprocate Anthony Kennedy’s embrace of the decision by doing the same for him. Colley, a Democrat, soon came to publicly regret supporting the more conservative Kennedy. Still, the associate justice wrote him a letter on June 20, 1991, that’s in the collection.

“You are more than one of the great attorneys in the history of our bar; you are one of the most gifted of teachers,” wrote Kennedy, who didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story. “You teach far beyond the formality of the law school. You teach in the courtroom, in practice, in your commitment to what is right and just.”

Beyond this, the collection includes items such as:

▪ Letters from California governors Pat Brown and Jerry Brown.

▪ A 1966 letter to Colley from then-U.S. Solicitor General and soon-to-be Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall. He thanked Colley for sending him a copy of his article, “Civil Action For Damages Arising Out of Violations of Civil Rights.”

▪ An apologetic 1976 letter to California Superior Court Justice Irving H. Perluss from San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, who’d failed to check a critical item about Colley. Perluss had written to Caen calling Colley “not only the finest attorney who ever has appeared in my court but he is a warm, compassionate, charitable man.”

The man behind the work

Colley noted in an undated letter to an unknown recipient in the center’s collection that for 25 years, he’d devoted a quarter of his time to pro bono work.

But there was a caveat, with Colley writing, “This has been no real sacrifice, because you, or others like you, have afforded me the rich harvest of academic success in my profession.”

Success meant never eating hamburger meat, which Colley associated with his impoverished youth in Alabama. His son Nat Colley remembered that when the family would eat hamburgers, his father would have a steak.

The Colleys also became among the first African American families to purchase a home in South Land Park, though in an era of mortgage redlining and open discrimination, they had to go to extreme lengths to do so. Steinberg noted in a state of the city address several years ago about how the Colleys had to have a white friend stand in as buyer.

Beyond this, Colley was fond of horses, becoming the first African American to serve on the California Horse Racing Commission and keeping a ranch in Elk Grove, where he would eventually die. Mazuri Colley remembered her grandfather taking her and her sisters to Santa Rosa to see horse races.

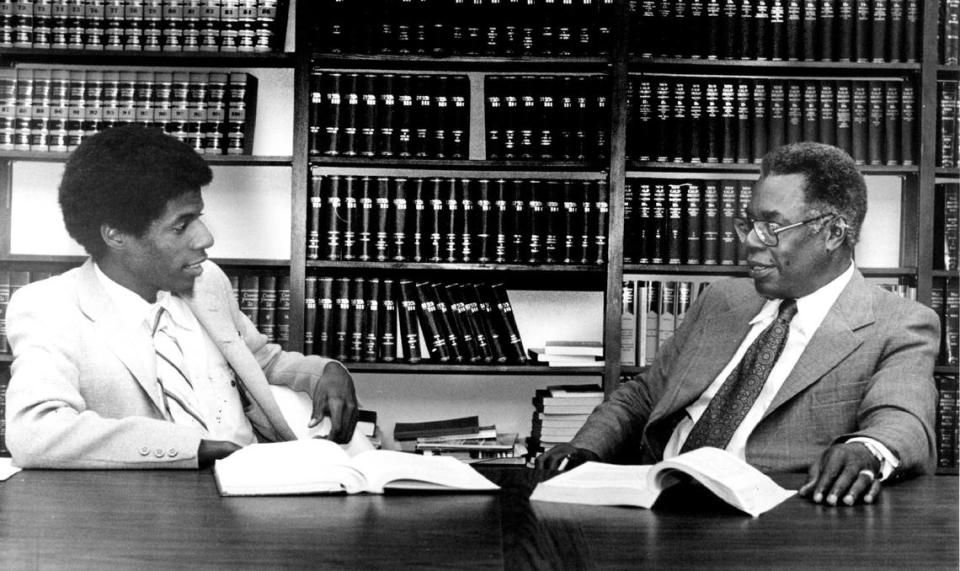

In later years, Colley worked with his daughter Natalie Lindsey and with Nat Colley, who each also became attorneys.

“There’s no question that he changed – that Sacramento was a different place because he was here and because of the work he did,” said Nat Colley, who now lives in the Minneapolis area and has transitioned from law to writing.

As for Mazuri Colley, she moved back to Sacramento from the Bay Area in recent years, works for Women’s Foundation California and serves on the board of Carrie’s Touch, a local nonprofit that raises awareness of cancer in Black women.

To her, the main message about her grandfather’s life is that everyone can do something.

“I just feel like we all can make a positive impact within the sphere and the realm that we’re in,” she said. “It doesn’t always have to seem like you have to do really big things or noteworthy things. Because it all adds up.”